Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

The key to gender equality and women’s empowerment

The face of poverty is female

2/3

2/3

It is estimated that women account for two-thirds of the 1.4 billion people currently living in extreme poverty and make up 60% of the 572 million working poor in the world.

The world is changing rapidly and this change has opened doors for women to fully participate in social, economic and political life. Despite this optimism, gender norms still hold women and girls back.

Sexual and reproductive health and rights are critical to achieving gender equality.

Why? Because when women are able to maintain good health their well-being is directly affected. There are fewer maternal deaths and less illness. Women are able to participate in education, and in all facets of life, free from violence. When women and girls can realize their sexual and reproductive health and rights they are more free to participate in social, economic and political life.

Sexual and reproductive health and rights: the key to gender equality

Sexual and reproductive health and rights are fundamental human rights. Having access to those rights will bring about huge changes to the lives of women and girls around the world. Only when women and girls have those rights will we have gender equality and only then will we be able to tackle some of the world’s most pressing problems.

In this animation we have used the stories of two girls to illustrate what happens when you give women and girls the power to decide for themselves and the ability to be in control of their own bodies.

It can make all the difference to individual lives as well as to the lives of families and the communities they live in.

Equal opportunities for all

This is what gender equality is all about

All individuals should have equal opportunities. But there are huge challenges to achieving equality. Society’s expectations for girls and women can limit their opportunities across social, economic and political life. Across the globe, women and girls still have lower status, fewer opportunities and lower income, less control over resources, and less power than men and boys. Son preference continues to deny girls the education they have a right to. And the burden of care work that women face impinges and intrudes on their opportunities in education and work.

Equal opportunities for all

This is what gender equality is all about

In the most extreme cases, gender norms can kill. We see examples of this in all corners of the world. Women die at the hands of their violent partners. Women die because they cannot access the abortion services they need. Women die of preventable causes in childbirth. Transgender people are murdered for being different. Gender inequality persists and prevents girls and women from reaping the benefits of our evolving world. It also limits possibilities for men and boys.

47,000 women

die every year due to complications of unsafe abortion.

70% of maternal deaths

occuring in developing countries could be avoided if the world doubled its investment in family planning and maternal and newborn health care.

74% of all maternal deaths

could be avoided if women had access to the interventions needed to address complications during pregnancy and childbirth.

Maternal Health

Control over their own fertility can allow women to reduce their chances of a high-risk pregnancy (including those that occur too late or early in life, or too soon after a previous birth) and associated complications. It can also reduce harmful reproductive stress and maternal nutritional depletion and reduce unsafe abortions.

EDUCATION

The education of women and girls is widely recognized as a powerful tool to empower them within their family and society, and as a key pathway to employment and earning.

Each additional year of schooling for girls improves their employment prospects, increases future earnings by about 10% and reduces infant mortality by up to 10%. Post-primary education has far stronger positive effects on empowerment outcomes than primary education. Lack of access to sexual and reproductive health and rights acts as a significant barrier to post-primary education for girls. For example, early marriage reduces girls’ access to education, and anticipation of an early marriage often prevents secondary education for girls.

Girls who undergo forced marriage and female genital mutilation face harmful health consequences and reduced educational opportunities. Sexual and reproductive health policies should be combined with educational policies to address quality and equity, including social pressures such as stigma, as these impact keenly on young mothers and girls who have abortions, and may prevent their return to school.

Education affected: Nepal

Early and forced marriage has terrible consequences for girls and young women. This film follows the story of Ashmita, a survivor of early marriage and forced to give up her education at a young age. She eventually completes her education, inspiring change within her community.

Discrimination against girls

Larger family size exacerbates and is exacerbated by son preference. This includes educational preference for boys, where girls are more likely than boys to be taken out of school to care for siblings. It has been observed that smaller family size can also be associated with parents less likely to discriminate by sex.

Convincing links have been shown between the caregiving roles and economic responsibilities of children in families living with HIV and disruptions to schooling for girls. Evidence indicates that HIV, among other sexually transmitted infections, exacerbates the gender-based inequalities that already exist in the education sector. In most cases this disadvantages girls in their access to quality education and also disadvantages women in their employment opportunities as educators and administrators.

Women and girls are not only biologically more at risk of contracting HIV, but gender norms also reinforce girls’ roles as care- givers and girls often provide economic support to their families, particularly given the educational preference for boys in many countries.

When a parent is ill, children’s school attendance drops because child labour may be needed to pay medical expenses, because families cannot afford to pay school fees, and because carers are needed for sick relatives: the impact of an increased domestic workload often falls disproportionately on girls. Once orphaned, adolescent girls may be ‘pawned’ to a relative or neighbour to work in return for money paid to the fostering family, or may seek work in towns (some in sex work and domestic work in the informal economy) in order to provide for the needs of younger children in their household. This has an impact on the life opportunities of young women, including their access to education.

Comprehensive sexuality education and positive behaviour change

Comprehensive sexuality education is important for young people to understand their rights and have the self-confidence to act on them. Comprehensive sexuality education can be a promising strategy by which to shift norms and attitudes, and empower young people to negotiate safe, consensual and enjoyable sex.

A review of 87 studies of comprehensive sexuality education programmes around the world showed that it increased knowledge, and two-thirds of programmes led to a positive impact on behaviour, including increased condom or contraceptive use, or reduced sexual risk-taking. However, such programmes are not available in most countries.

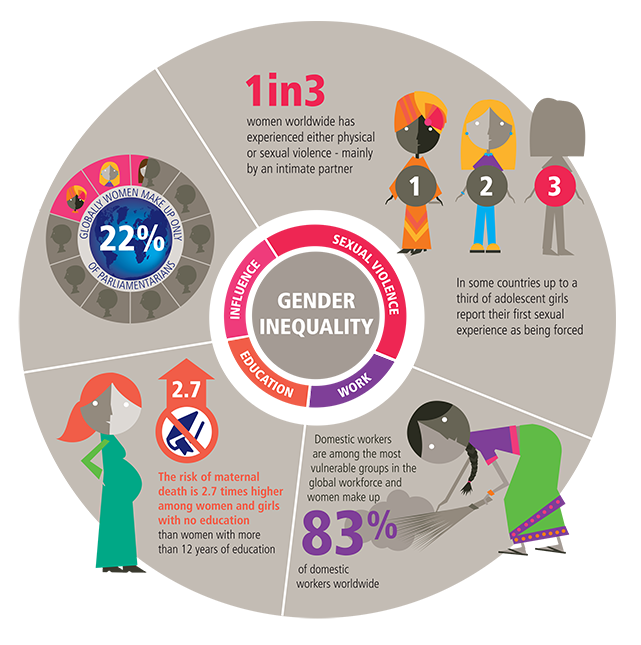

Sexual and gender-based violence

Globally, one in three women experience either intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence during their lifetime. Spanning intimate partner violence, female genital mutilation, early and forced marriage, and violence as a weapon of war, sexual and gender- based violence is a major public health concern in all corners of the world, a barrier to women’s empowerment and gender equality, and a constraint on individual and societal development, with high economic costs.

Women who experience violence are more at risk of unwanted pregnancies, maternal and infant mortality, and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, and such violence can cause direct and long-term physical and mental health consequences. Women who experience violence from their partners are less likely to earn a living and are less able to care for their children or participate meaningfully in community activities or social interaction that might help end the abuse. In many societies, women who are raped or sexually abused are stigmatized and isolated, which impacts not only on their well- being, but also on their social participation, opportunities and quality of life.

Reaching women in Afghanistan: Reducing HIV and gender-based violence

There is a direct and cyclical link between HIV and sexual and gender-based violence. Women who have experienced intimate partner violence are 55% more likely to be infected with HIV.

Often sexual and reproductive health services are the first point of contact for survivors who require counselling and health checks. HIV can be reduced through combating and sexual and gender-based violence services.

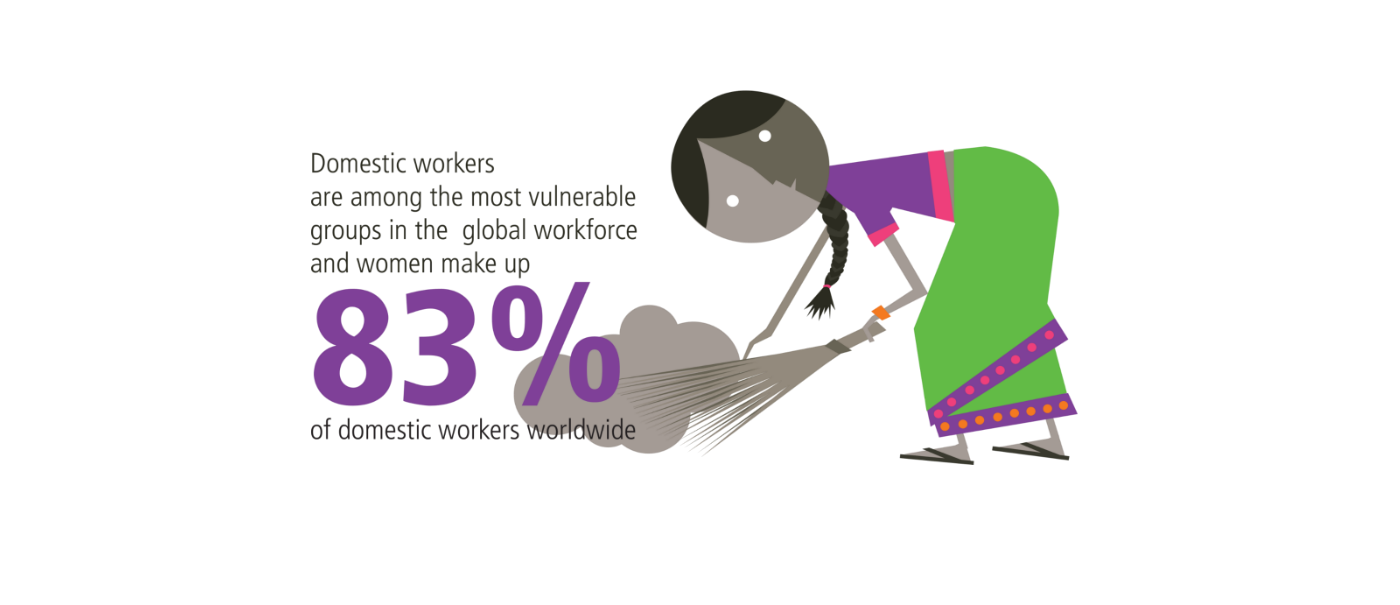

ECONOMIC

Among the 1.6 billion workers receiving regular wages in the labour market, female workers are paid, on average, significantly less than male workers. Women in most countries earn on average only 60% to 75% of men’s wages. They are also over-represented as micro-entrepreneurs and small farmers, doing low-paid, low-productivity work in small firms or farms. This gendered gap in productivity and earnings is not because women are less capable, but because of women’s lower educational levels and their limited access to resources, as well as social perceptions about the role of women.

Unpaid care burden

Women across the world shoulder a disproportionate amount of unpaid care work. Unpaid care includes, but is not limited to, child care, elder care, taking care of ill family members, cooking and cleaning. Women devote 1 to 3 hours more a day to housework than men; 2 to 10 times the amount of time a day to care, and 1 to 4 hours less a day to market activities. Unpaid care burdens affect women’s access to economic opportunities. In the formal market, women juggle paid work with unpaid work and often face a ‘motherhood penalty’, so discrimination in the workplace because of their real or perceived roles as carers.

Women may also face difficulties in getting a job in the formal economy, as they may not have the flexibility or childcare support to work contracted hours or travel to their workplace. Because of unpaid care burdens, women may seek work in the informal economy, a sector which can allow for more flexible working hours and conditions, but which is less regulated. Work in the informal economy is often insecure and precarious and has specific implications for the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women.

The formal and informal markets

Female workers are paid less and women are overrepresented in low productivity positions because of lower education and the social perceptions about the roles of women. Regulation of rights in the workplace is very low plus discrimination and stigma put vulnerable groups (immigrants, sex workers) at risk of violence, HIV, lower wages, unable to access other sexual and reproductive health and right services.

Economic empowerment

The extent to which women’s increased entry into the labour force may be empowering depends on the context, the reasons for women’s economic participation, the existence of regulatory frameworks to support women’s economic participation, and the type and conditions of the work.

True economic empowerment and stability comes from ensuring that programming on women’s economic empowerment and regulatory frameworks across both the formal and informal economies include consideration of women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights.

POLITICAL INEQUALITIES

Women’s low participation in public and political life is often shaped by the legal framework and by the nature of formal political institutions such as political parties and parliamentary structures, and electoral systems and processes. But gender norms and economic and social factors also limit women’s opportunities and capabilities to participate in decision making.

As a result, women’s domestic roles and responsibilities are over-emphasised, so they often have less time to engage in informal and formal decision making and political activities outside of the household. Other reasons women have low participation in public and formal political life is because party politics and strategic resources are dominated by men.

These inequalities mean that women often face barriers that men don’t - such as lack of access to networks, resources and limits on mobility, all of which restrain women from political candidacy. Violence against female politicians is not uncommon. Candidates face discrimination based on sexuality, ethnicity, religion, disability, health status and marital and family status.

Changing social norms from the ground up

Getting more women into office does not by itself guarantee women’s substantive influence on political decision making or guarantee political decisions that further women’s rights, gender equality or other gender outcomes. Women are not a homogeneous group but come from very varied backgrounds. Increasing women’s representation and participation in governance is not simply about numbers and influence, but is also about the need for women’s strategic interests and gender equality concerns to be addressed in public policy decisions and resource allocations so that these better support women’s rights in general.

Challenging the social structures at the grassroots level which perpetuate inequalities can lead to an increase in sexual and reproductive health access. This leads to empowerment and not just inserting women into positions within the political framework.

Research shows that women’s combined strength, through collective action and women’s movements, can play a central role in building the momentum for progressive policy and legal reforms, changing adverse social norms and promoting accountability.

Peace building

Of particular concern to the international community is the low political participation and engagement of women in peace building and reconstruction processes in post‑conflict situations across the world.Sexual violence is a major barrier to women’s participation in peacebuilding and recovery. Violence against ‘political’ women speaking up in public, defending human rights or seeking political office is very common in post‑conflict countries and strongly dissuades women from participating in public life, let alone seeking political office.

IPPF urges governments, United Nations agencies, multi-lateral institutions and civil society to:

1. Support an enabling environment so that sexual and reproductive health and rights and gender equality become a reality.

- Governments must prioritize the inclusion of sexual and reproductive health and rights within global agendas such as the post-2015 sustainable development framework. Governments should include sexual and reproductive health and rights in national plans to ensure political prioritization and continued investment in sexual and reproductive health and rights.

- Governments must prioritize sexual and reproductive health and rights within the context of both health and gender equality. At the national level, this requires commitment and investment from the ministry of health and the ministry of gender/women, as sexual and reproductive health and rights span the range of women’s human rights.

- Governments, UN agencies, multi-lateral institutions and civil society mustprioritize sexual and reproductive health and rights in order to tackle harmful gender norms. They should establish policies and deliver programmes which support not only the health of women and girls, but also their socio-economic development more broadly. There must be a strong focus on girls and the prevention of sexual and gender-based violence, including harmful traditional practices that compromise their health and limit development in other areas of their lives.

- Governments must include sexual and reproductive health and rights in regulatory frameworks that support women’s access to decent work. Such frameworks should be expanded across the formal and informal economy.

- e. Donors and civil society must include sexual and reproductive health and rights in programming on women’s economic empowerment in order to support women’s access to decent work.

Access to safe and legal abortion in France

We need laws that defend our sexual and reproductive health and rights and that protect us from harm.

This is the story of Juliette in France. Although French law permits abortion on wide grounds, she found it extremely difficult to find the correct legal and medical information when faced with an unplanned pregnancy.

2. Continue and increase financial and political commitment to sexual and reproductive health and rights in order to sustain the success of health interventions and to expand and increase possibilities for gender equality and the empowerment of girls and women.

- Donors, multi-lateral institutions and national governments should continue and increase investment in the full range of sexual and reproductive health and rights services, including rights-based family planning. Particular attention should be paid to investing in maternal health and HIV prevention, both of which are leading causes of death among women of reproductive age in low and middle-income countries.

- Governments and civil society must ensure that the post-2015 sustainable development financing mechanisms and strategies that detail what financing will cover – such as the Global Financing Facility and the updated strategy on women’s and children’s health – prioritize the sexual and reproductive health of women and girls. Donors and multi-lateral institutions must engage civil society meaningfully in the creation of these financing structures as well as national financing plans.

Delivering family planning in Kenya

This is the story of Beatrice Akoth in Kenya who has had no access to family planning and has struggled to cope with 9 children. Her daughter is determined to have a different life and has been happy with the family planning services she received from IPPF's member, Family Health Options Kenya.

Kenya's government made a commitment in 2012 to make sure everyone had access to affordable reproductive health services. Their investment in family planning increased to US $8 million.

3. Measure the things that matter.

- Governments must prioritize greater investment and effort to fill knowledge gaps and collect robust data. UN agencies and multi-lateral institutions should work with governments to increase data collection, disaggregated by sex and age, on sexual and reproductive health and rights and other core areas relating to gender equality.

- Donors and multi-lateral institutions should increase investment to support civil society and academic networks to examine the links between sexual and reproductive health and the empowerment of girls and women. More rigorous research is needed on the impact of sexual and reproductive health and rights interventions in education, and the links with women’s economic participation (particularly in agriculture) and representation in political and public life. Establishing these links could have a significant impact on policy and programme interventions related to sexual and reproductive health and rights, gender equality, and the empowerment of women and girls.

Measuring gender equality and empowerment

We now have a unique opportunity to end gender inequality. But to achieve this we must have accurate data which reflects the true status of women's sexual and reproductive health and rights. Collecting the missing information on the the issues which really matter will make a difference on what programmes are funded and how can achieve proper empowerment of women

4. Engage men and boys as partners in gender transformative change by ensuring that sexual and reproductive health and rights are a reality for all.

Civil society organizations, donors and multi-lateral institutions must involve men and boys as partners in programmes on sexual and reproductive health and rights, gender equality, and the empowerment of women and girls.

Men as champions for gender justice

Evidence shows that where men and boys are engaged in tackling gender inequality and promoting women’s choices, the resulting outcomes are positive and men and women are able to enjoy equitable, healthy and happy relationships.

This is Ustaz Muhammad Nursalim's story. He is an imam born and raised in Madura, an island in East Java:

"My wife is busy as head teacher of the village kindergarten, so I handle all the domestic duties. We hear of cases of husbands abusing their wives. They don’t know how to manage their anger. So our home has become the emergency consultation room for couples. I give advice based on what I apply daily in my own marriage. Besides teaching, I often give talks at boys’ circumcision or coming of age celebrations. I tailor my words to the people I meet. Yesterday, for instance, I talked about how to respect our daughters and girls in general.”

5. Take steps to eliminate sexual and gender-based violence against women and girls by ensuring implementation of legislation that protects women from violence, and ensuring access to sexual and reproductive health services that meet the needs of women and girls, particularly in fragile and conflict affected contexts.

- Governments must ensure that domestic laws protect women from sexual and gender- based violence in line with international obligations and commitments under human rights treaties and that these laws are enforced at all times.

- Governments, donors and civil society should support the integration of sexual and reproductive health, HIV, and sexual and gender-based violence services in order to promote women’s health and empowerment.

- Governments, donors and civil society must ensure that sexual violence is addressed as part of promoting women’s political participation and engagement in peace building and post-conflict reconstruction.

Escaping sexual and gender based violence in Syria

This is the story of Layla. At 15, she was forced into marriage then was beaten and raped by her husband’s brother. She fled from her home and was forced into sex work. Luckily, Layla received counselling and sexual health services from IPPF's Member Association, the Syrian Family Planning Association. She regained her health and confidence and now helps other young women who are survivors of sexual and gender based violence.

6. Continue and increase investment at the grassroots level, to build women’s individual and collective capacity to participate in political and public life.

Donors, multi-lateral institutions and civil society should continue and increase funding to grassroots organizations that build the capacity of women to participate individually and collectively across social, economic, political and public life.

Tea parties breaking down taboos in Pakistan

Umm e Kalsoom is a 23-year-old woman in the Muzaffarabad region of Pakistan. She started to run tea parties for girls in her local area so that young women could share their sexual and reproductive health concerns in a safe environment without discrimination. Talking about these issues is a cultural taboo for these girls. She also wanted to inspire young girls within the communities to mobilize other girls and women. She says: "If I ever have my own daughter I would like her to be a confident and empowered girl, who knows and exercises her rights to make informed decision in her life." At first the community was very reluctant to participate. But now they discuss issues such as HIV, early marriage and sexual abuse, as well as abortion and contraceptives. For most women the tea parties taught them that these are their human rights.

when

Subject

Contraception, Comprehensive Sex Education, Gender equality, Maternal Healthcare, Gynaecological

HEALTH

Poor sexual and reproductive health outcomes represent one-third of the total global burden of disease for women between the ages of 15 and 44 years, with unsafe sex a major risk factor for death and disability among women and girls in low and middle-income countries.

HIV

Globally, HIV is the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age and the second leading cause of death among adolescents. Women and girls have a greater physical vulnerability to HIV infection than men or boys. This risk is compounded by social norms, gender inequality, poverty and violence. Women living with HIV are also more likely to face stigmatization, infertility, and even abuse and abandonment, contributing to their disempowerment.