Today the world celebrates the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), a tradition that still puts at risk the life and health of millions of women and girls.

FGM refers to different types of cutting and the removal of external female genitalia, and in its most extreme forms in the partial stitching together of the vulva (infibulation). All of these practices can lead to recurring infections, fistula, infertility, HIV and even death. FGM often leads to pain during menstruation and sex and difficulties during childbirth are very likely, resulting in a lifelong threat to women's health and well-being.

The practice persists even in countries, like Kenya, where it has been officially outlawed, because it's strictly bonded to religious beliefs and traditional rites of passage.

What can be done to eradicate female genital mutilation?

We asked the advice of Dr Edna Adan, founder of IPPF Somaliland Family Health Association (SOFHA) and the first person to start the fight against FGM in her country, and of Amal Ahmed, SOFHA's Executive Director.

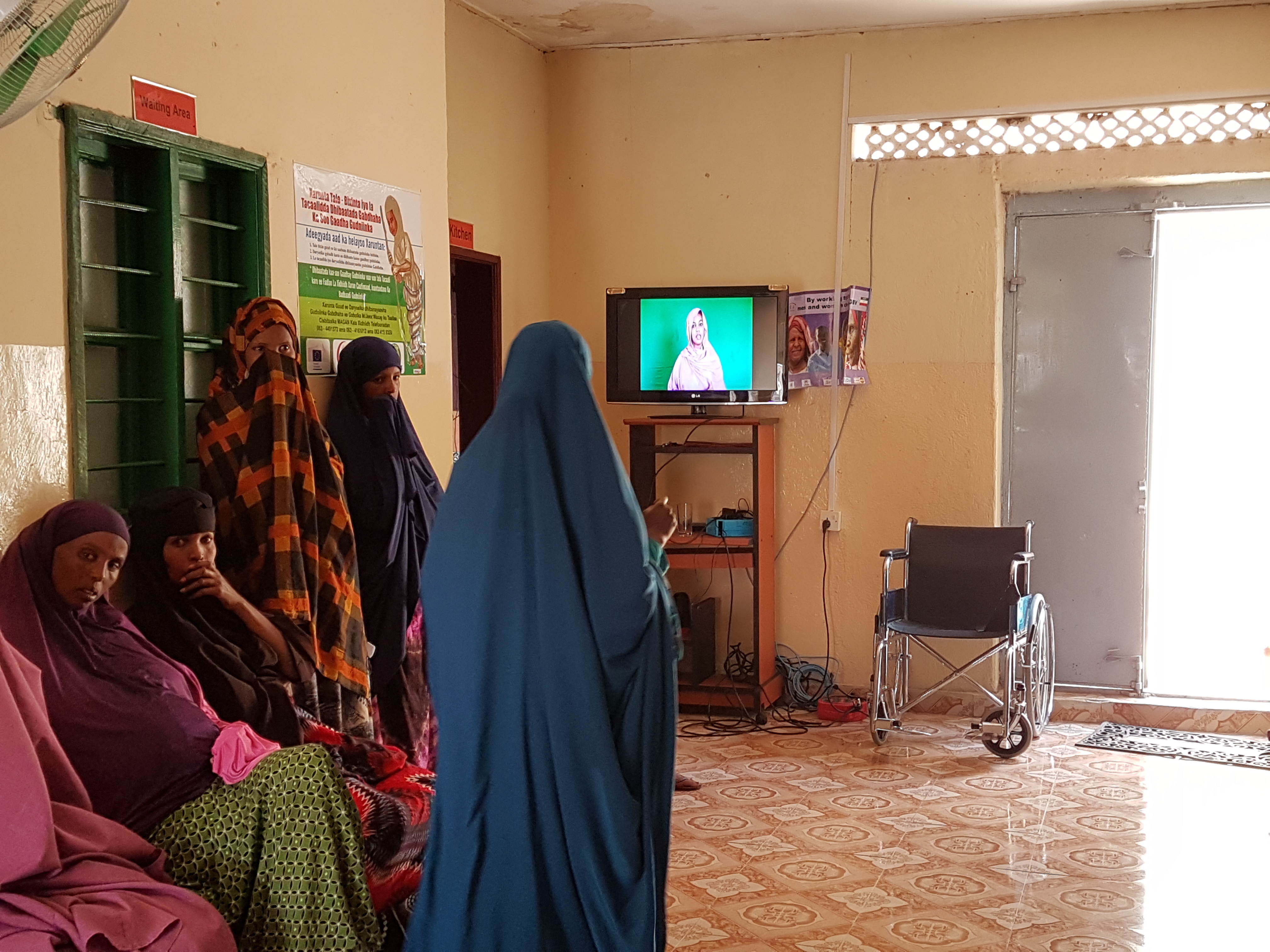

SOFHA's staff deals with FGM complications on a daily basis and is actively working to lead a cultural change in Somaliland where 98% of women are FGM survivors and a vast majority of them has undergone infibulation.

Here is their key strategy to try tackle FGM.

1- Go down to the community and talk about things people understand and care about.

"You need to get trusted people to go to the community, to the villages. Don’t talk about human rights or girl’s integrity and don’t directly talk about FGM. Talk about health, they want their girls to be healthy. Tell them about the risk of infertility and HIV, about the pain and recurring infections." -Edna

"We approach mothers from the maternal ward, we discuss with them and try to earn their trust. We explain them the health risks and invite them to keep coming to our clinics." - Amal

2- Engage religious leaders.

"FGM is not an Islam requirement, it's a traditional mutilation.

Religious leaders are trusted in the community and can help fight this misconception, affirming that FGM has no place in any religion, that God created the girls and forbids FGM." - Edna

"When we tell mothers that FGM is against Islam, then we get their attention." - Amal

3- Collaborate with educators to inform and engage young people.

"Go to the elite of educators. IPPF since last year is funding a 3-years project to institutionalise FGM campaigns by involving the Minister of Education, to bring FGM to high-schools and universities, to form the next generation of educators and medical professionals to become change-leaders." - Edna

"First years of school are crucial to engage parents, because girls are cut during those years.

"In high schools and universities, we also invite young people to think about what they will do as parents, and to intervene at home for their younger siblings." - Amal

4- Engage men, especially fathers.

"I knew that what was done to me was wrong because my father was against it, but most men don't know what happens, they think that FGM is like male circumcision. Let it become a male issue, men doctors talking to men.

Engaging fathers is the best strategy. Tell them they could never be grandfathers if they let their daughter be cut." - Edna

"Men consider reproductive health a woman issue. We brought them to a maternal hospital, they've never been there before. We also invite young men to become activists." - Amal

5- Don't rush to legislation, invest in cultural shift.

"Resolutions are easy, but their implementation is difficult, unless you want to convict every mother and look after all children. You need to convince the majority, then convict the minority." -Edna

"I'm from the diaspora community, when the practice has been abandoned. When my aunt visited us from Somaliland, and saw how horrified we were about her idea to cut her daughter, she changed her mind." - Amal

6- Invest in relationships.

"Trust and personal relationships are extremely important, both with the community, the government and the civil society. We've created a national taskforce to learn from each other and collaborate across the country.

We're also collaborating with four ministries, Education, Health, Social Affairs and Religious Affairs.

Through IPPF's project, we want to mainstream FGM campaigns to build the capacity of these institutions so they can keep intervening after the end of the project.

It's important to remember that the focus is not on you, but on the elimination of this dangerous practice." - Amal