Spotlight

A selection of stories from across the Federation

France, Germany, Poland, United Kingdom, United States, Colombia, India, Tunisia

Abortion Rights: Latest Decisions and Developments around the World

The global landscape of abortion rights continues to evolve in 2024, with new legislation and feminist movements fighting for better access. Let's take a trip around the world to see the latest developments.

Most Popular This Week

France, Germany, Poland, United Kingdom, United States, Colombia, India, Tunisia

Abortion Rights: Latest Decisions and Developments around the World

Over the past 30 years, more than

Palestine

In their own words: The people providing sexual and reproductive health care under bombardment in Gaza

Week after week, heavy Israeli bombardment from air, land, and sea, has continued across most of the Gaza Strip.

Vanuatu

When getting to the hospital is difficult, Vanuatu mobile outreach can save lives

In the mountains of Kumera on Tanna Island, Vanuatu, the village women of Kamahaul normally spend over 10,000 Vatu ($83 USD) to travel to the nearest hospital.

Vanuatu

Sex: changing minds and winning hearts in Tanna, Vanuatu

“Very traditional.” These two words are often used to describe the people of Tanna in Vanuatu, one of the most populated islands in the small country in the Pacific.

Vanuatu

Vanuatu cyclone response: The mental health toll on humanitarian providers

Girls and women from nearby villages flock to mobile health clinics set up by the Vanuatu Family Health Association (VFHA).

Cook Islands

Trans & Proud: Being Transgender in the Cook Islands

It’s a scene like many others around the world: a loving family pour over childhood photos, giggling and reminiscing about the memories.

Cook Islands

In Pictures: The activists who helped win LGBTI+ rights in the Cook Islands

The Cook Islands has removed a law that criminalizes homosexuality, in a huge victory for the local LGBTI+ community.

Filter our stories by:

| 29 November 2017

Meet the college student who uses his music to battle the stigma surrounding HIV

Milan Khadka was just ten years old when he lost both his parents to HIV. “When I lost my parents, I used to feel so alone, like I didn’t have anyone in the world,” he says. “Whenever I saw other children getting love from others, I used to feel that I also might get that kind of love if I hadn’t lost my parents.” Like thousands of Nepali children, Milan’s parents left Nepal for India in search of work. Milan grew up in India until he was ten, when his mother died of AIDS-related causes. The family then returned to Nepal, but just eight months later, his father also died, and Milan was left in the care of his grandmother. “After I lost my parents, I went for VCT [voluntary counselling and testing] to check if I had HIV in my body,” Milan says. “After I was diagnosed as HIV positive, slowly all the people in the area found out about my status and there was so much discrimination. My friends at school didn’t want to sit with me and they humiliated and bullied me,” he says. “At home, I had a separate sleeping area and sleeping materials, separate dishes and a separate comb for my hair. I had to sleep alone.” Things began to improve for Milan when he met a local woman called Lakshmi Kunwar. After discovering she was HIV-positive, Lakshmi had dedicated her life to helping people living with HIV in Palpa, working as a community home-based care mobiliser for the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN) and other organisations. Struck by the plight of this small, orphaned boy, Lakshmi spoke to Milan’s family and teachers, who in turn spoke to his school mates. “After she spoke to my teachers, they started to support me,” Milan says. “And after getting information about HIV, my school friends started to like me and share things with me. And they said: ‘Milan has no one in this world, so we are the ones who must be with him. Who knows that what happened to him might not happen to us?” Lakshmi mentored him through school and college, encouraging him in his schoolwork. “Lakshmi is more than my mother,” he says. “My mother only gave birth to me but Lakshmi has looked after me all this time. Even if my mother was alive today, she might not do all the things for me that Lakshmi has done.” Milan went on to become a grade A student, regularly coming top of his class and leaving school with flying colours. Today, twenty-one-year-old Milan lives a busy and fulfilling life, juggling his college studies, his work as a community home-based care (CHBC) mobiliser for FPAN and a burgeoning music career. When not studying for a Bachelor’s of education at university in Tansen, he works as a CHBC mobiliser for FPAN, visiting villages in the area to raise awareness about how to prevent and treat HIV, and to distribute contraception. He also offers support to children living with HIV, explaining to them how he lost his parents and faced discrimination but now leads a happy and successful life. “There are 40 children in this area living with HIV,” he says. “I talk to them, collect information from them and help them get the support they need. And I tell them: ‘If I had given up at that time, I would not be like this now. So you also shouldn’t give up, and you have to live your life.” Watch Milan's story below:

| 24 April 2024

Meet the college student who uses his music to battle the stigma surrounding HIV

Milan Khadka was just ten years old when he lost both his parents to HIV. “When I lost my parents, I used to feel so alone, like I didn’t have anyone in the world,” he says. “Whenever I saw other children getting love from others, I used to feel that I also might get that kind of love if I hadn’t lost my parents.” Like thousands of Nepali children, Milan’s parents left Nepal for India in search of work. Milan grew up in India until he was ten, when his mother died of AIDS-related causes. The family then returned to Nepal, but just eight months later, his father also died, and Milan was left in the care of his grandmother. “After I lost my parents, I went for VCT [voluntary counselling and testing] to check if I had HIV in my body,” Milan says. “After I was diagnosed as HIV positive, slowly all the people in the area found out about my status and there was so much discrimination. My friends at school didn’t want to sit with me and they humiliated and bullied me,” he says. “At home, I had a separate sleeping area and sleeping materials, separate dishes and a separate comb for my hair. I had to sleep alone.” Things began to improve for Milan when he met a local woman called Lakshmi Kunwar. After discovering she was HIV-positive, Lakshmi had dedicated her life to helping people living with HIV in Palpa, working as a community home-based care mobiliser for the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN) and other organisations. Struck by the plight of this small, orphaned boy, Lakshmi spoke to Milan’s family and teachers, who in turn spoke to his school mates. “After she spoke to my teachers, they started to support me,” Milan says. “And after getting information about HIV, my school friends started to like me and share things with me. And they said: ‘Milan has no one in this world, so we are the ones who must be with him. Who knows that what happened to him might not happen to us?” Lakshmi mentored him through school and college, encouraging him in his schoolwork. “Lakshmi is more than my mother,” he says. “My mother only gave birth to me but Lakshmi has looked after me all this time. Even if my mother was alive today, she might not do all the things for me that Lakshmi has done.” Milan went on to become a grade A student, regularly coming top of his class and leaving school with flying colours. Today, twenty-one-year-old Milan lives a busy and fulfilling life, juggling his college studies, his work as a community home-based care (CHBC) mobiliser for FPAN and a burgeoning music career. When not studying for a Bachelor’s of education at university in Tansen, he works as a CHBC mobiliser for FPAN, visiting villages in the area to raise awareness about how to prevent and treat HIV, and to distribute contraception. He also offers support to children living with HIV, explaining to them how he lost his parents and faced discrimination but now leads a happy and successful life. “There are 40 children in this area living with HIV,” he says. “I talk to them, collect information from them and help them get the support they need. And I tell them: ‘If I had given up at that time, I would not be like this now. So you also shouldn’t give up, and you have to live your life.” Watch Milan's story below:

| 24 October 2017

"We visit them in their real lives, because they may not have time to go to clinics to check their status"

Few people are at higher risk of HIV infection or STIs than sex workers. Although sex work is illegal in Thailand, like in so many countries many turn a blind eye. JiHye Hong is a volunteer with PPAT, the Planned Parenthood Association of Thailand, and she works with the HIV and STIs prevention team in and around Bangkok. One month into her volunteer project, she has already been out on 17 visits to women who work in high risk entertainment centres. “They can be a target group,” explains JiHye. “Some of them can’t speak Thai, and they don’t have Thai ID cards. They are young.” The HIV and STIs prevention team is part of PPAT’s Sexual and Reproductive Health department in Bangkok. It works with many partners in the city, including secondary schools and MSM (men who have sex with men) groups, as well as the owners of entertainment businesses. They go out to them on door-to-door visits. “We visit them in their real lives, because they may not have time to go to clinics to check their status,” says JiHye. “Usually we spend about an hour for educational sessions, and then we do activities together to check if they’ve understood. It’s the part we can all do together and enjoy.” The team JiHye works with takes a large picture book with them on their visits, one full of descriptions of symptoms and signs of STIs, including graphic images that show real cases of the results of HIV/AIDs and STIs. It’s a very clear way of make sure everyone understands the impact of STIs. Reaction to page titles and pictures which include “Syphilis” “Gonorrhoea” “Genital Herpes” and “Vaginal Candidiasis” are what you might expect. “They are often quite shocked, especially young people. They ask a lot of questions and share concerns,” says JiHye. The books and leaflets used by the PPAT team don’t just shock though. They also explain issues such as sexuality and sexual orientations too, to raise awareness and help those taking part in a session understand about diversity and equality. After the education sessions, tests are offered for HIV and/or Syphilis on the spot to anyone who wants one. For Thai nationals, up to two HIV tests a year are free, funded by the Thai Government. An HIV test after that is 140 Thai Baht or about four US Dollars. A test for Syphilis costs 50 Bhat. “An HIV rapid test takes less than 30 minutes to produce a result which is about 99% accurate,” says JiHye. The nurse will also take blood samples back to the lab for even more accurate testing, which takes two to three days.” At the same time, the groups are also given advice on how it use condoms correctly, with a model penis for demonstration, and small PPAT gift bags are handed out, containing condoms, a card with the phone numbers for PPATs clinics and a small carry case JiHye, who is from South Korea originally, is a graduate in public health at Tulane University, New Orleans. That inspired her to volunteer for work with PPAT. “I’ve really learned that people around the world are the same and equal, and a right to access to health services should be universal for all, regardless of ages, gender, sexual orientations, nationality, religions, and jobs.”

| 24 April 2024

"We visit them in their real lives, because they may not have time to go to clinics to check their status"

Few people are at higher risk of HIV infection or STIs than sex workers. Although sex work is illegal in Thailand, like in so many countries many turn a blind eye. JiHye Hong is a volunteer with PPAT, the Planned Parenthood Association of Thailand, and she works with the HIV and STIs prevention team in and around Bangkok. One month into her volunteer project, she has already been out on 17 visits to women who work in high risk entertainment centres. “They can be a target group,” explains JiHye. “Some of them can’t speak Thai, and they don’t have Thai ID cards. They are young.” The HIV and STIs prevention team is part of PPAT’s Sexual and Reproductive Health department in Bangkok. It works with many partners in the city, including secondary schools and MSM (men who have sex with men) groups, as well as the owners of entertainment businesses. They go out to them on door-to-door visits. “We visit them in their real lives, because they may not have time to go to clinics to check their status,” says JiHye. “Usually we spend about an hour for educational sessions, and then we do activities together to check if they’ve understood. It’s the part we can all do together and enjoy.” The team JiHye works with takes a large picture book with them on their visits, one full of descriptions of symptoms and signs of STIs, including graphic images that show real cases of the results of HIV/AIDs and STIs. It’s a very clear way of make sure everyone understands the impact of STIs. Reaction to page titles and pictures which include “Syphilis” “Gonorrhoea” “Genital Herpes” and “Vaginal Candidiasis” are what you might expect. “They are often quite shocked, especially young people. They ask a lot of questions and share concerns,” says JiHye. The books and leaflets used by the PPAT team don’t just shock though. They also explain issues such as sexuality and sexual orientations too, to raise awareness and help those taking part in a session understand about diversity and equality. After the education sessions, tests are offered for HIV and/or Syphilis on the spot to anyone who wants one. For Thai nationals, up to two HIV tests a year are free, funded by the Thai Government. An HIV test after that is 140 Thai Baht or about four US Dollars. A test for Syphilis costs 50 Bhat. “An HIV rapid test takes less than 30 minutes to produce a result which is about 99% accurate,” says JiHye. The nurse will also take blood samples back to the lab for even more accurate testing, which takes two to three days.” At the same time, the groups are also given advice on how it use condoms correctly, with a model penis for demonstration, and small PPAT gift bags are handed out, containing condoms, a card with the phone numbers for PPATs clinics and a small carry case JiHye, who is from South Korea originally, is a graduate in public health at Tulane University, New Orleans. That inspired her to volunteer for work with PPAT. “I’ve really learned that people around the world are the same and equal, and a right to access to health services should be universal for all, regardless of ages, gender, sexual orientations, nationality, religions, and jobs.”

| 12 September 2017

"I said to myself: I will live and I will let others living with HIV live"

Lakshmi Kunwar married young, at the age of 17. Shortly afterwards, Lakshmi’s husband, who worked as a migrant labourer in India, was diagnosed with HIV and died. “At that time, I was completely unaware of HIV,” Lakshmi says. “My husband had information that if someone is diagnosed with HIV, they will die very soon. So after he was diagnosed, he didn’t eat anything and he became very ill and after six months he died. He gave up.” Lakshmi contracted HIV too, and the early years of living with it were arduous. “It was a huge burden,” she says. “I didn’t want to eat anything so I ate very little. My weight at the time was 44 kilograms. I had different infections in my skin and allergies in her body. It was really a difficult time for me. … I was just waiting for my death. I got support from my home and in-laws but my neighbours started to discriminate against me – like they said HIV may transfer via different insects and parasites like lice.” Dedicating her life to help others Lakshmi’s life began to improve when she came across an organisation in Palpa that offered support to people living with HIV (PLHIV). “They told me that there is medicine for PLHIV which will prolong our lives,” she explains. “They took me to Kathmandu, where I got training and information on HIV and I started taking ARVs [antiretroviral drugs].” In Kathmandu Lakshmi decided that she would dedicate the rest of her life to supporting people living with HIV. “I made a plan that I would come back home [to Palpa], disclose my status and then do social work with other people living with HIV, so that they too may have hope to live. I said to myself: I will live and I will let others living with HIV live”. Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 24 April 2024

"I said to myself: I will live and I will let others living with HIV live"

Lakshmi Kunwar married young, at the age of 17. Shortly afterwards, Lakshmi’s husband, who worked as a migrant labourer in India, was diagnosed with HIV and died. “At that time, I was completely unaware of HIV,” Lakshmi says. “My husband had information that if someone is diagnosed with HIV, they will die very soon. So after he was diagnosed, he didn’t eat anything and he became very ill and after six months he died. He gave up.” Lakshmi contracted HIV too, and the early years of living with it were arduous. “It was a huge burden,” she says. “I didn’t want to eat anything so I ate very little. My weight at the time was 44 kilograms. I had different infections in my skin and allergies in her body. It was really a difficult time for me. … I was just waiting for my death. I got support from my home and in-laws but my neighbours started to discriminate against me – like they said HIV may transfer via different insects and parasites like lice.” Dedicating her life to help others Lakshmi’s life began to improve when she came across an organisation in Palpa that offered support to people living with HIV (PLHIV). “They told me that there is medicine for PLHIV which will prolong our lives,” she explains. “They took me to Kathmandu, where I got training and information on HIV and I started taking ARVs [antiretroviral drugs].” In Kathmandu Lakshmi decided that she would dedicate the rest of her life to supporting people living with HIV. “I made a plan that I would come back home [to Palpa], disclose my status and then do social work with other people living with HIV, so that they too may have hope to live. I said to myself: I will live and I will let others living with HIV live”. Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 08 September 2017

“Attitudes of younger people to HIV are not changing fast"

“When I was 14, I was trafficked to India,” says 35-year-old Lakshmi Lama. “I was made unconscious and was taken to Mumbai. When I woke up, I didn’t even know that I had been trafficked, I didn’t know where I was.” Every year, thousands of Nepali women and girls are trafficked to India, some lured with the promise of domestic work only to find themselves in brothels or working as sex slaves. The visa-free border with India means the actual number of women and girls trafficked from Nepal is likely to be much higher. The earthquake of April 2015 also led to a surge in trafficking: women and girls living in tents or temporary housing, and young orphaned children were particularly vulnerable to traffickers. “I was in Mumbai for three years,” says Lakshmi. “Then I managed to send letters and photographs to my parents and eventually they came to Mumbai and helped rescue me from that place". During her time in India, Lakshmi contracted HIV. Life after her diagnosis was tough, Lakshmi explains. “When I was diagnosed with HIV, people used to discriminate saying, “you’ve got HIV and it might transfer to us so don’t come to our home, don’t touch us,’” she says. “It’s very challenging for people living with HIV in Nepal. People really suffer.” Today, Lakshmi lives in Banepa, a busy town around 25 kilometres east of Kathmandu. Things began to improve for her, she says, when she started attending HIV awareness classes run by Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN). Eventually she herself trained as an FPAN peer educator, and she now works hard visiting communities in Kavre, raising awareness about HIV prevention and treatment, and bringing people together to tackle stigma around the virus. The government needs to do far more to tackle HIV stigma in Nepal, particularly at village level, Lakshmi says, “Attitudes of younger people to HIV are not changing fast. People still say to me: ‘you have HIV, you may die soon’. There is so much stigma and discrimination in this community.” Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 24 April 2024

“Attitudes of younger people to HIV are not changing fast"

“When I was 14, I was trafficked to India,” says 35-year-old Lakshmi Lama. “I was made unconscious and was taken to Mumbai. When I woke up, I didn’t even know that I had been trafficked, I didn’t know where I was.” Every year, thousands of Nepali women and girls are trafficked to India, some lured with the promise of domestic work only to find themselves in brothels or working as sex slaves. The visa-free border with India means the actual number of women and girls trafficked from Nepal is likely to be much higher. The earthquake of April 2015 also led to a surge in trafficking: women and girls living in tents or temporary housing, and young orphaned children were particularly vulnerable to traffickers. “I was in Mumbai for three years,” says Lakshmi. “Then I managed to send letters and photographs to my parents and eventually they came to Mumbai and helped rescue me from that place". During her time in India, Lakshmi contracted HIV. Life after her diagnosis was tough, Lakshmi explains. “When I was diagnosed with HIV, people used to discriminate saying, “you’ve got HIV and it might transfer to us so don’t come to our home, don’t touch us,’” she says. “It’s very challenging for people living with HIV in Nepal. People really suffer.” Today, Lakshmi lives in Banepa, a busy town around 25 kilometres east of Kathmandu. Things began to improve for her, she says, when she started attending HIV awareness classes run by Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN). Eventually she herself trained as an FPAN peer educator, and she now works hard visiting communities in Kavre, raising awareness about HIV prevention and treatment, and bringing people together to tackle stigma around the virus. The government needs to do far more to tackle HIV stigma in Nepal, particularly at village level, Lakshmi says, “Attitudes of younger people to HIV are not changing fast. People still say to me: ‘you have HIV, you may die soon’. There is so much stigma and discrimination in this community.” Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 08 September 2017

'My neighbours used to discriminate against me and I suffered violence at the hands of my community'

"My husband used to work in India, and when he came back, he got ill and died," says Durga Thame. "We didn’t know that he was HIV-positive, but then then later my daughter got sick with typhoid and went to hospital and was diagnosed with HIV and died, and then I was tested and was found positive." Her story is tragic, but one all too familiar for the women living in this region. Men often travel to India in search of work, where they contract HIV and upon their return infect their wives. For Durga, the death of her husband and daughter and her own HIV positive diagnosis threw her into despair. "My neighbours used to discriminate against me … and I suffered violence at the hands of my community. Everybody used to say that they couldn’t eat whatever I cooked because they might get HIV." Then Durga heard about HIV education classes run by the Palpa branch of the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), a short bus journey up the road in Tansen, the capital of Palpa. "At those meetings, I got information about HIV," she says. "When I came back to my village, I began telling my neighbours about HIV. They came to know the facts and they realised it was a myth that HIV could be transferred by sharing food. Then they began treating me well." FPAN ran nutrition, hygiene, sanitation and livelihood classes that helped Durga turn the fortunes of her small homestead around. Durga sells goats and hens, and with these earnings supports her family – her father-in-law and her surviving daughter, who she says has not yet been tested for HIV. "I want to educate my daughter," she says. "I really hope I can provide a better education for her." Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 24 April 2024

'My neighbours used to discriminate against me and I suffered violence at the hands of my community'

"My husband used to work in India, and when he came back, he got ill and died," says Durga Thame. "We didn’t know that he was HIV-positive, but then then later my daughter got sick with typhoid and went to hospital and was diagnosed with HIV and died, and then I was tested and was found positive." Her story is tragic, but one all too familiar for the women living in this region. Men often travel to India in search of work, where they contract HIV and upon their return infect their wives. For Durga, the death of her husband and daughter and her own HIV positive diagnosis threw her into despair. "My neighbours used to discriminate against me … and I suffered violence at the hands of my community. Everybody used to say that they couldn’t eat whatever I cooked because they might get HIV." Then Durga heard about HIV education classes run by the Palpa branch of the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), a short bus journey up the road in Tansen, the capital of Palpa. "At those meetings, I got information about HIV," she says. "When I came back to my village, I began telling my neighbours about HIV. They came to know the facts and they realised it was a myth that HIV could be transferred by sharing food. Then they began treating me well." FPAN ran nutrition, hygiene, sanitation and livelihood classes that helped Durga turn the fortunes of her small homestead around. Durga sells goats and hens, and with these earnings supports her family – her father-in-law and her surviving daughter, who she says has not yet been tested for HIV. "I want to educate my daughter," she says. "I really hope I can provide a better education for her." Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 21 August 2017

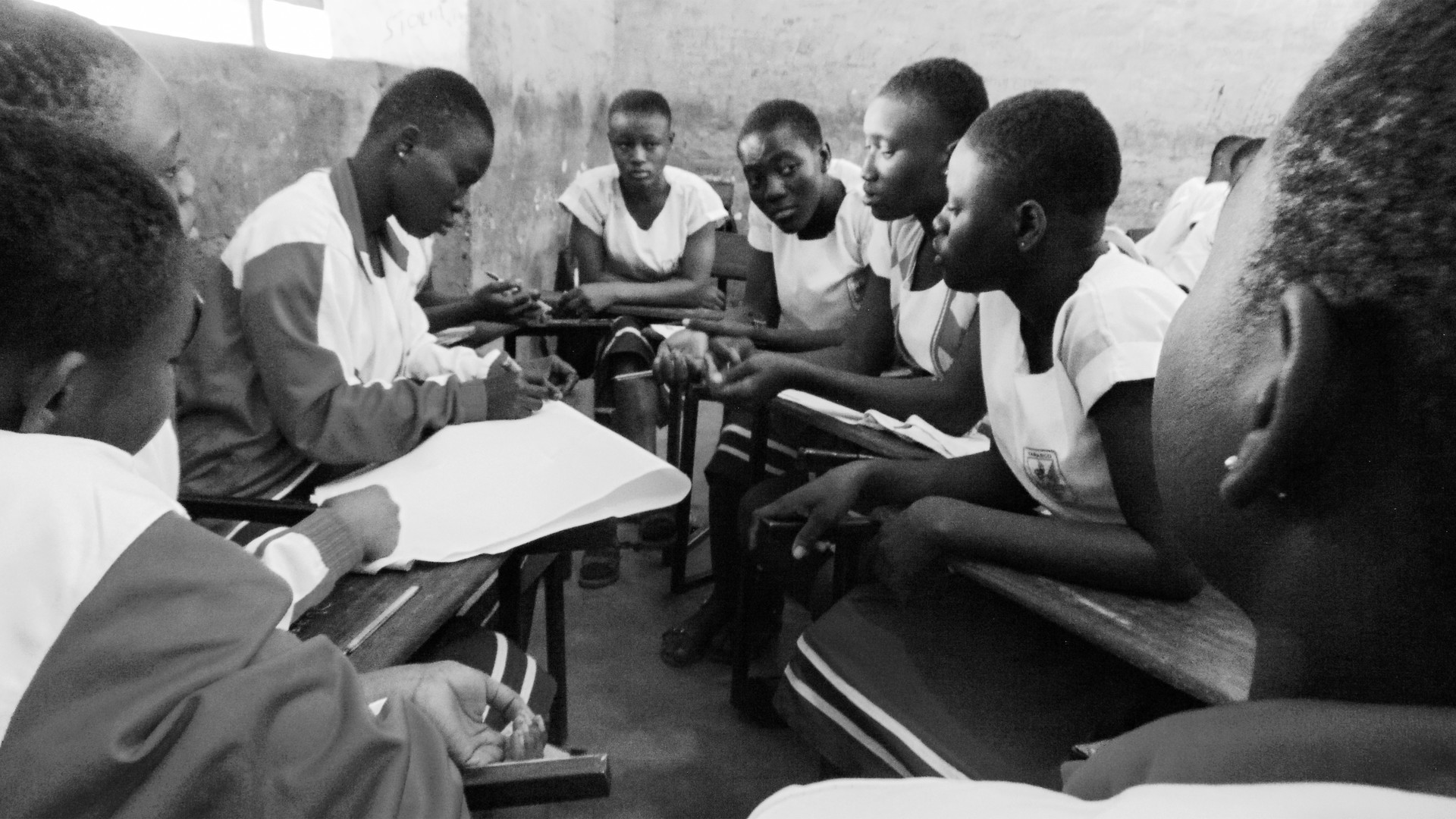

How youth volunteers are leading the conversation on HIV with young people in Nepal

Mala Neupane is just 18 years old, but is already an experienced volunteer for the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN). Mala lives in Tansen, the hillside capital of Palpa, a region of rolling hills, pine forests and lush terraced fields in western Nepal. She works as a community home-based care mobiliser focusing on HIV: her job involves travelling to villages around Tansen to provide people with information about HIV and contraception. “Before, the community had very little knowledge regarding HIV and there used to be so much stigma and discrimination,” she says. “But later, when the Community Health Based Carers (CHBCs) started working in those communities, they had more knowledge and less stigma.” The youth of the volunteers proved an effective tool during their conversations with villagers. “At first, when they talked to people about family planning, they were not receptive: they felt resistance to using those devices,” Mala explains. “The CHBCs said to them: ‘young people like us are doing this kind of work, so why are you feeling such hesitation?’ After talking with them, they became ready to use contraceptives.” Her age is also important for connecting with young people, in a society of rapid change, she says. “Because we are young, we may know more about what young people’s needs and wants are. We can talk to young people about what family planning methods might be suitable for them, and what the options are.” “Young people’s involvement [in FPAN programmes] is very important to helping out young people like us.” It’s a simple message, but one reaping rich rewards for the lives and wellbeing of people in Palpa.

| 24 April 2024

How youth volunteers are leading the conversation on HIV with young people in Nepal

Mala Neupane is just 18 years old, but is already an experienced volunteer for the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN). Mala lives in Tansen, the hillside capital of Palpa, a region of rolling hills, pine forests and lush terraced fields in western Nepal. She works as a community home-based care mobiliser focusing on HIV: her job involves travelling to villages around Tansen to provide people with information about HIV and contraception. “Before, the community had very little knowledge regarding HIV and there used to be so much stigma and discrimination,” she says. “But later, when the Community Health Based Carers (CHBCs) started working in those communities, they had more knowledge and less stigma.” The youth of the volunteers proved an effective tool during their conversations with villagers. “At first, when they talked to people about family planning, they were not receptive: they felt resistance to using those devices,” Mala explains. “The CHBCs said to them: ‘young people like us are doing this kind of work, so why are you feeling such hesitation?’ After talking with them, they became ready to use contraceptives.” Her age is also important for connecting with young people, in a society of rapid change, she says. “Because we are young, we may know more about what young people’s needs and wants are. We can talk to young people about what family planning methods might be suitable for them, and what the options are.” “Young people’s involvement [in FPAN programmes] is very important to helping out young people like us.” It’s a simple message, but one reaping rich rewards for the lives and wellbeing of people in Palpa.

| 29 November 2017

Meet the college student who uses his music to battle the stigma surrounding HIV

Milan Khadka was just ten years old when he lost both his parents to HIV. “When I lost my parents, I used to feel so alone, like I didn’t have anyone in the world,” he says. “Whenever I saw other children getting love from others, I used to feel that I also might get that kind of love if I hadn’t lost my parents.” Like thousands of Nepali children, Milan’s parents left Nepal for India in search of work. Milan grew up in India until he was ten, when his mother died of AIDS-related causes. The family then returned to Nepal, but just eight months later, his father also died, and Milan was left in the care of his grandmother. “After I lost my parents, I went for VCT [voluntary counselling and testing] to check if I had HIV in my body,” Milan says. “After I was diagnosed as HIV positive, slowly all the people in the area found out about my status and there was so much discrimination. My friends at school didn’t want to sit with me and they humiliated and bullied me,” he says. “At home, I had a separate sleeping area and sleeping materials, separate dishes and a separate comb for my hair. I had to sleep alone.” Things began to improve for Milan when he met a local woman called Lakshmi Kunwar. After discovering she was HIV-positive, Lakshmi had dedicated her life to helping people living with HIV in Palpa, working as a community home-based care mobiliser for the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN) and other organisations. Struck by the plight of this small, orphaned boy, Lakshmi spoke to Milan’s family and teachers, who in turn spoke to his school mates. “After she spoke to my teachers, they started to support me,” Milan says. “And after getting information about HIV, my school friends started to like me and share things with me. And they said: ‘Milan has no one in this world, so we are the ones who must be with him. Who knows that what happened to him might not happen to us?” Lakshmi mentored him through school and college, encouraging him in his schoolwork. “Lakshmi is more than my mother,” he says. “My mother only gave birth to me but Lakshmi has looked after me all this time. Even if my mother was alive today, she might not do all the things for me that Lakshmi has done.” Milan went on to become a grade A student, regularly coming top of his class and leaving school with flying colours. Today, twenty-one-year-old Milan lives a busy and fulfilling life, juggling his college studies, his work as a community home-based care (CHBC) mobiliser for FPAN and a burgeoning music career. When not studying for a Bachelor’s of education at university in Tansen, he works as a CHBC mobiliser for FPAN, visiting villages in the area to raise awareness about how to prevent and treat HIV, and to distribute contraception. He also offers support to children living with HIV, explaining to them how he lost his parents and faced discrimination but now leads a happy and successful life. “There are 40 children in this area living with HIV,” he says. “I talk to them, collect information from them and help them get the support they need. And I tell them: ‘If I had given up at that time, I would not be like this now. So you also shouldn’t give up, and you have to live your life.” Watch Milan's story below:

| 24 April 2024

Meet the college student who uses his music to battle the stigma surrounding HIV

Milan Khadka was just ten years old when he lost both his parents to HIV. “When I lost my parents, I used to feel so alone, like I didn’t have anyone in the world,” he says. “Whenever I saw other children getting love from others, I used to feel that I also might get that kind of love if I hadn’t lost my parents.” Like thousands of Nepali children, Milan’s parents left Nepal for India in search of work. Milan grew up in India until he was ten, when his mother died of AIDS-related causes. The family then returned to Nepal, but just eight months later, his father also died, and Milan was left in the care of his grandmother. “After I lost my parents, I went for VCT [voluntary counselling and testing] to check if I had HIV in my body,” Milan says. “After I was diagnosed as HIV positive, slowly all the people in the area found out about my status and there was so much discrimination. My friends at school didn’t want to sit with me and they humiliated and bullied me,” he says. “At home, I had a separate sleeping area and sleeping materials, separate dishes and a separate comb for my hair. I had to sleep alone.” Things began to improve for Milan when he met a local woman called Lakshmi Kunwar. After discovering she was HIV-positive, Lakshmi had dedicated her life to helping people living with HIV in Palpa, working as a community home-based care mobiliser for the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN) and other organisations. Struck by the plight of this small, orphaned boy, Lakshmi spoke to Milan’s family and teachers, who in turn spoke to his school mates. “After she spoke to my teachers, they started to support me,” Milan says. “And after getting information about HIV, my school friends started to like me and share things with me. And they said: ‘Milan has no one in this world, so we are the ones who must be with him. Who knows that what happened to him might not happen to us?” Lakshmi mentored him through school and college, encouraging him in his schoolwork. “Lakshmi is more than my mother,” he says. “My mother only gave birth to me but Lakshmi has looked after me all this time. Even if my mother was alive today, she might not do all the things for me that Lakshmi has done.” Milan went on to become a grade A student, regularly coming top of his class and leaving school with flying colours. Today, twenty-one-year-old Milan lives a busy and fulfilling life, juggling his college studies, his work as a community home-based care (CHBC) mobiliser for FPAN and a burgeoning music career. When not studying for a Bachelor’s of education at university in Tansen, he works as a CHBC mobiliser for FPAN, visiting villages in the area to raise awareness about how to prevent and treat HIV, and to distribute contraception. He also offers support to children living with HIV, explaining to them how he lost his parents and faced discrimination but now leads a happy and successful life. “There are 40 children in this area living with HIV,” he says. “I talk to them, collect information from them and help them get the support they need. And I tell them: ‘If I had given up at that time, I would not be like this now. So you also shouldn’t give up, and you have to live your life.” Watch Milan's story below:

| 24 October 2017

"We visit them in their real lives, because they may not have time to go to clinics to check their status"

Few people are at higher risk of HIV infection or STIs than sex workers. Although sex work is illegal in Thailand, like in so many countries many turn a blind eye. JiHye Hong is a volunteer with PPAT, the Planned Parenthood Association of Thailand, and she works with the HIV and STIs prevention team in and around Bangkok. One month into her volunteer project, she has already been out on 17 visits to women who work in high risk entertainment centres. “They can be a target group,” explains JiHye. “Some of them can’t speak Thai, and they don’t have Thai ID cards. They are young.” The HIV and STIs prevention team is part of PPAT’s Sexual and Reproductive Health department in Bangkok. It works with many partners in the city, including secondary schools and MSM (men who have sex with men) groups, as well as the owners of entertainment businesses. They go out to them on door-to-door visits. “We visit them in their real lives, because they may not have time to go to clinics to check their status,” says JiHye. “Usually we spend about an hour for educational sessions, and then we do activities together to check if they’ve understood. It’s the part we can all do together and enjoy.” The team JiHye works with takes a large picture book with them on their visits, one full of descriptions of symptoms and signs of STIs, including graphic images that show real cases of the results of HIV/AIDs and STIs. It’s a very clear way of make sure everyone understands the impact of STIs. Reaction to page titles and pictures which include “Syphilis” “Gonorrhoea” “Genital Herpes” and “Vaginal Candidiasis” are what you might expect. “They are often quite shocked, especially young people. They ask a lot of questions and share concerns,” says JiHye. The books and leaflets used by the PPAT team don’t just shock though. They also explain issues such as sexuality and sexual orientations too, to raise awareness and help those taking part in a session understand about diversity and equality. After the education sessions, tests are offered for HIV and/or Syphilis on the spot to anyone who wants one. For Thai nationals, up to two HIV tests a year are free, funded by the Thai Government. An HIV test after that is 140 Thai Baht or about four US Dollars. A test for Syphilis costs 50 Bhat. “An HIV rapid test takes less than 30 minutes to produce a result which is about 99% accurate,” says JiHye. The nurse will also take blood samples back to the lab for even more accurate testing, which takes two to three days.” At the same time, the groups are also given advice on how it use condoms correctly, with a model penis for demonstration, and small PPAT gift bags are handed out, containing condoms, a card with the phone numbers for PPATs clinics and a small carry case JiHye, who is from South Korea originally, is a graduate in public health at Tulane University, New Orleans. That inspired her to volunteer for work with PPAT. “I’ve really learned that people around the world are the same and equal, and a right to access to health services should be universal for all, regardless of ages, gender, sexual orientations, nationality, religions, and jobs.”

| 24 April 2024

"We visit them in their real lives, because they may not have time to go to clinics to check their status"

Few people are at higher risk of HIV infection or STIs than sex workers. Although sex work is illegal in Thailand, like in so many countries many turn a blind eye. JiHye Hong is a volunteer with PPAT, the Planned Parenthood Association of Thailand, and she works with the HIV and STIs prevention team in and around Bangkok. One month into her volunteer project, she has already been out on 17 visits to women who work in high risk entertainment centres. “They can be a target group,” explains JiHye. “Some of them can’t speak Thai, and they don’t have Thai ID cards. They are young.” The HIV and STIs prevention team is part of PPAT’s Sexual and Reproductive Health department in Bangkok. It works with many partners in the city, including secondary schools and MSM (men who have sex with men) groups, as well as the owners of entertainment businesses. They go out to them on door-to-door visits. “We visit them in their real lives, because they may not have time to go to clinics to check their status,” says JiHye. “Usually we spend about an hour for educational sessions, and then we do activities together to check if they’ve understood. It’s the part we can all do together and enjoy.” The team JiHye works with takes a large picture book with them on their visits, one full of descriptions of symptoms and signs of STIs, including graphic images that show real cases of the results of HIV/AIDs and STIs. It’s a very clear way of make sure everyone understands the impact of STIs. Reaction to page titles and pictures which include “Syphilis” “Gonorrhoea” “Genital Herpes” and “Vaginal Candidiasis” are what you might expect. “They are often quite shocked, especially young people. They ask a lot of questions and share concerns,” says JiHye. The books and leaflets used by the PPAT team don’t just shock though. They also explain issues such as sexuality and sexual orientations too, to raise awareness and help those taking part in a session understand about diversity and equality. After the education sessions, tests are offered for HIV and/or Syphilis on the spot to anyone who wants one. For Thai nationals, up to two HIV tests a year are free, funded by the Thai Government. An HIV test after that is 140 Thai Baht or about four US Dollars. A test for Syphilis costs 50 Bhat. “An HIV rapid test takes less than 30 minutes to produce a result which is about 99% accurate,” says JiHye. The nurse will also take blood samples back to the lab for even more accurate testing, which takes two to three days.” At the same time, the groups are also given advice on how it use condoms correctly, with a model penis for demonstration, and small PPAT gift bags are handed out, containing condoms, a card with the phone numbers for PPATs clinics and a small carry case JiHye, who is from South Korea originally, is a graduate in public health at Tulane University, New Orleans. That inspired her to volunteer for work with PPAT. “I’ve really learned that people around the world are the same and equal, and a right to access to health services should be universal for all, regardless of ages, gender, sexual orientations, nationality, religions, and jobs.”

| 12 September 2017

"I said to myself: I will live and I will let others living with HIV live"

Lakshmi Kunwar married young, at the age of 17. Shortly afterwards, Lakshmi’s husband, who worked as a migrant labourer in India, was diagnosed with HIV and died. “At that time, I was completely unaware of HIV,” Lakshmi says. “My husband had information that if someone is diagnosed with HIV, they will die very soon. So after he was diagnosed, he didn’t eat anything and he became very ill and after six months he died. He gave up.” Lakshmi contracted HIV too, and the early years of living with it were arduous. “It was a huge burden,” she says. “I didn’t want to eat anything so I ate very little. My weight at the time was 44 kilograms. I had different infections in my skin and allergies in her body. It was really a difficult time for me. … I was just waiting for my death. I got support from my home and in-laws but my neighbours started to discriminate against me – like they said HIV may transfer via different insects and parasites like lice.” Dedicating her life to help others Lakshmi’s life began to improve when she came across an organisation in Palpa that offered support to people living with HIV (PLHIV). “They told me that there is medicine for PLHIV which will prolong our lives,” she explains. “They took me to Kathmandu, where I got training and information on HIV and I started taking ARVs [antiretroviral drugs].” In Kathmandu Lakshmi decided that she would dedicate the rest of her life to supporting people living with HIV. “I made a plan that I would come back home [to Palpa], disclose my status and then do social work with other people living with HIV, so that they too may have hope to live. I said to myself: I will live and I will let others living with HIV live”. Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 24 April 2024

"I said to myself: I will live and I will let others living with HIV live"

Lakshmi Kunwar married young, at the age of 17. Shortly afterwards, Lakshmi’s husband, who worked as a migrant labourer in India, was diagnosed with HIV and died. “At that time, I was completely unaware of HIV,” Lakshmi says. “My husband had information that if someone is diagnosed with HIV, they will die very soon. So after he was diagnosed, he didn’t eat anything and he became very ill and after six months he died. He gave up.” Lakshmi contracted HIV too, and the early years of living with it were arduous. “It was a huge burden,” she says. “I didn’t want to eat anything so I ate very little. My weight at the time was 44 kilograms. I had different infections in my skin and allergies in her body. It was really a difficult time for me. … I was just waiting for my death. I got support from my home and in-laws but my neighbours started to discriminate against me – like they said HIV may transfer via different insects and parasites like lice.” Dedicating her life to help others Lakshmi’s life began to improve when she came across an organisation in Palpa that offered support to people living with HIV (PLHIV). “They told me that there is medicine for PLHIV which will prolong our lives,” she explains. “They took me to Kathmandu, where I got training and information on HIV and I started taking ARVs [antiretroviral drugs].” In Kathmandu Lakshmi decided that she would dedicate the rest of her life to supporting people living with HIV. “I made a plan that I would come back home [to Palpa], disclose my status and then do social work with other people living with HIV, so that they too may have hope to live. I said to myself: I will live and I will let others living with HIV live”. Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 08 September 2017

“Attitudes of younger people to HIV are not changing fast"

“When I was 14, I was trafficked to India,” says 35-year-old Lakshmi Lama. “I was made unconscious and was taken to Mumbai. When I woke up, I didn’t even know that I had been trafficked, I didn’t know where I was.” Every year, thousands of Nepali women and girls are trafficked to India, some lured with the promise of domestic work only to find themselves in brothels or working as sex slaves. The visa-free border with India means the actual number of women and girls trafficked from Nepal is likely to be much higher. The earthquake of April 2015 also led to a surge in trafficking: women and girls living in tents or temporary housing, and young orphaned children were particularly vulnerable to traffickers. “I was in Mumbai for three years,” says Lakshmi. “Then I managed to send letters and photographs to my parents and eventually they came to Mumbai and helped rescue me from that place". During her time in India, Lakshmi contracted HIV. Life after her diagnosis was tough, Lakshmi explains. “When I was diagnosed with HIV, people used to discriminate saying, “you’ve got HIV and it might transfer to us so don’t come to our home, don’t touch us,’” she says. “It’s very challenging for people living with HIV in Nepal. People really suffer.” Today, Lakshmi lives in Banepa, a busy town around 25 kilometres east of Kathmandu. Things began to improve for her, she says, when she started attending HIV awareness classes run by Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN). Eventually she herself trained as an FPAN peer educator, and she now works hard visiting communities in Kavre, raising awareness about HIV prevention and treatment, and bringing people together to tackle stigma around the virus. The government needs to do far more to tackle HIV stigma in Nepal, particularly at village level, Lakshmi says, “Attitudes of younger people to HIV are not changing fast. People still say to me: ‘you have HIV, you may die soon’. There is so much stigma and discrimination in this community.” Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 24 April 2024

“Attitudes of younger people to HIV are not changing fast"

“When I was 14, I was trafficked to India,” says 35-year-old Lakshmi Lama. “I was made unconscious and was taken to Mumbai. When I woke up, I didn’t even know that I had been trafficked, I didn’t know where I was.” Every year, thousands of Nepali women and girls are trafficked to India, some lured with the promise of domestic work only to find themselves in brothels or working as sex slaves. The visa-free border with India means the actual number of women and girls trafficked from Nepal is likely to be much higher. The earthquake of April 2015 also led to a surge in trafficking: women and girls living in tents or temporary housing, and young orphaned children were particularly vulnerable to traffickers. “I was in Mumbai for three years,” says Lakshmi. “Then I managed to send letters and photographs to my parents and eventually they came to Mumbai and helped rescue me from that place". During her time in India, Lakshmi contracted HIV. Life after her diagnosis was tough, Lakshmi explains. “When I was diagnosed with HIV, people used to discriminate saying, “you’ve got HIV and it might transfer to us so don’t come to our home, don’t touch us,’” she says. “It’s very challenging for people living with HIV in Nepal. People really suffer.” Today, Lakshmi lives in Banepa, a busy town around 25 kilometres east of Kathmandu. Things began to improve for her, she says, when she started attending HIV awareness classes run by Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN). Eventually she herself trained as an FPAN peer educator, and she now works hard visiting communities in Kavre, raising awareness about HIV prevention and treatment, and bringing people together to tackle stigma around the virus. The government needs to do far more to tackle HIV stigma in Nepal, particularly at village level, Lakshmi says, “Attitudes of younger people to HIV are not changing fast. People still say to me: ‘you have HIV, you may die soon’. There is so much stigma and discrimination in this community.” Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 08 September 2017

'My neighbours used to discriminate against me and I suffered violence at the hands of my community'

"My husband used to work in India, and when he came back, he got ill and died," says Durga Thame. "We didn’t know that he was HIV-positive, but then then later my daughter got sick with typhoid and went to hospital and was diagnosed with HIV and died, and then I was tested and was found positive." Her story is tragic, but one all too familiar for the women living in this region. Men often travel to India in search of work, where they contract HIV and upon their return infect their wives. For Durga, the death of her husband and daughter and her own HIV positive diagnosis threw her into despair. "My neighbours used to discriminate against me … and I suffered violence at the hands of my community. Everybody used to say that they couldn’t eat whatever I cooked because they might get HIV." Then Durga heard about HIV education classes run by the Palpa branch of the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), a short bus journey up the road in Tansen, the capital of Palpa. "At those meetings, I got information about HIV," she says. "When I came back to my village, I began telling my neighbours about HIV. They came to know the facts and they realised it was a myth that HIV could be transferred by sharing food. Then they began treating me well." FPAN ran nutrition, hygiene, sanitation and livelihood classes that helped Durga turn the fortunes of her small homestead around. Durga sells goats and hens, and with these earnings supports her family – her father-in-law and her surviving daughter, who she says has not yet been tested for HIV. "I want to educate my daughter," she says. "I really hope I can provide a better education for her." Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 24 April 2024

'My neighbours used to discriminate against me and I suffered violence at the hands of my community'

"My husband used to work in India, and when he came back, he got ill and died," says Durga Thame. "We didn’t know that he was HIV-positive, but then then later my daughter got sick with typhoid and went to hospital and was diagnosed with HIV and died, and then I was tested and was found positive." Her story is tragic, but one all too familiar for the women living in this region. Men often travel to India in search of work, where they contract HIV and upon their return infect their wives. For Durga, the death of her husband and daughter and her own HIV positive diagnosis threw her into despair. "My neighbours used to discriminate against me … and I suffered violence at the hands of my community. Everybody used to say that they couldn’t eat whatever I cooked because they might get HIV." Then Durga heard about HIV education classes run by the Palpa branch of the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN), a short bus journey up the road in Tansen, the capital of Palpa. "At those meetings, I got information about HIV," she says. "When I came back to my village, I began telling my neighbours about HIV. They came to know the facts and they realised it was a myth that HIV could be transferred by sharing food. Then they began treating me well." FPAN ran nutrition, hygiene, sanitation and livelihood classes that helped Durga turn the fortunes of her small homestead around. Durga sells goats and hens, and with these earnings supports her family – her father-in-law and her surviving daughter, who she says has not yet been tested for HIV. "I want to educate my daughter," she says. "I really hope I can provide a better education for her." Stories Read more stories about our work with people living with HIV

| 21 August 2017

How youth volunteers are leading the conversation on HIV with young people in Nepal

Mala Neupane is just 18 years old, but is already an experienced volunteer for the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN). Mala lives in Tansen, the hillside capital of Palpa, a region of rolling hills, pine forests and lush terraced fields in western Nepal. She works as a community home-based care mobiliser focusing on HIV: her job involves travelling to villages around Tansen to provide people with information about HIV and contraception. “Before, the community had very little knowledge regarding HIV and there used to be so much stigma and discrimination,” she says. “But later, when the Community Health Based Carers (CHBCs) started working in those communities, they had more knowledge and less stigma.” The youth of the volunteers proved an effective tool during their conversations with villagers. “At first, when they talked to people about family planning, they were not receptive: they felt resistance to using those devices,” Mala explains. “The CHBCs said to them: ‘young people like us are doing this kind of work, so why are you feeling such hesitation?’ After talking with them, they became ready to use contraceptives.” Her age is also important for connecting with young people, in a society of rapid change, she says. “Because we are young, we may know more about what young people’s needs and wants are. We can talk to young people about what family planning methods might be suitable for them, and what the options are.” “Young people’s involvement [in FPAN programmes] is very important to helping out young people like us.” It’s a simple message, but one reaping rich rewards for the lives and wellbeing of people in Palpa.

| 24 April 2024

How youth volunteers are leading the conversation on HIV with young people in Nepal

Mala Neupane is just 18 years old, but is already an experienced volunteer for the Family Planning Association of Nepal (FPAN). Mala lives in Tansen, the hillside capital of Palpa, a region of rolling hills, pine forests and lush terraced fields in western Nepal. She works as a community home-based care mobiliser focusing on HIV: her job involves travelling to villages around Tansen to provide people with information about HIV and contraception. “Before, the community had very little knowledge regarding HIV and there used to be so much stigma and discrimination,” she says. “But later, when the Community Health Based Carers (CHBCs) started working in those communities, they had more knowledge and less stigma.” The youth of the volunteers proved an effective tool during their conversations with villagers. “At first, when they talked to people about family planning, they were not receptive: they felt resistance to using those devices,” Mala explains. “The CHBCs said to them: ‘young people like us are doing this kind of work, so why are you feeling such hesitation?’ After talking with them, they became ready to use contraceptives.” Her age is also important for connecting with young people, in a society of rapid change, she says. “Because we are young, we may know more about what young people’s needs and wants are. We can talk to young people about what family planning methods might be suitable for them, and what the options are.” “Young people’s involvement [in FPAN programmes] is very important to helping out young people like us.” It’s a simple message, but one reaping rich rewards for the lives and wellbeing of people in Palpa.