Spotlight

A selection of stories from across the Federation

What does the year 2024 hold for us?

As the new year begins, we take a look at the trends and challenges ahead for sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Most Popular This Week

Palestine

In their own words: The people providing sexual and reproductive health care under bombardment in Gaza

Week after week, heavy Israeli bombardment from air, land, and sea, has continued across most of the Gaza Strip.

Vanuatu

When getting to the hospital is difficult, Vanuatu mobile outreach can save lives

In the mountains of Kumera on Tanna Island, Vanuatu, the village women of Kamahaul normally spend over 10,000 Vatu ($83 USD) to travel to the nearest hospital.

Vanuatu

Sex: changing minds and winning hearts in Tanna, Vanuatu

“Very traditional.” These two words are often used to describe the people of Tanna in Vanuatu, one of the most populated islands in the small country in the Pacific.

Vanuatu

Vanuatu cyclone response: The mental health toll on humanitarian providers

Girls and women from nearby villages flock to mobile health clinics set up by the Vanuatu Family Health Association (VFHA).

Cook Islands

Trans & Proud: Being Transgender in the Cook Islands

It’s a scene like many others around the world: a loving family pour over childhood photos, giggling and reminiscing about the memories.

Cook Islands

In Pictures: The activists who helped win LGBTI+ rights in the Cook Islands

The Cook Islands has removed a law that criminalizes homosexuality, in a huge victory for the local LGBTI+ community.

Cook Islands

Dean and the Cook Islands Condom Car

On the island of Rarotonga, the main island of the Cook Islands in the South Pacific, a little white van makes its rounds on the palm-tree lined circular road.

Filter our stories by:

| 22 January 2018

"We are non-judgemental; we embark on a mutual learning process."

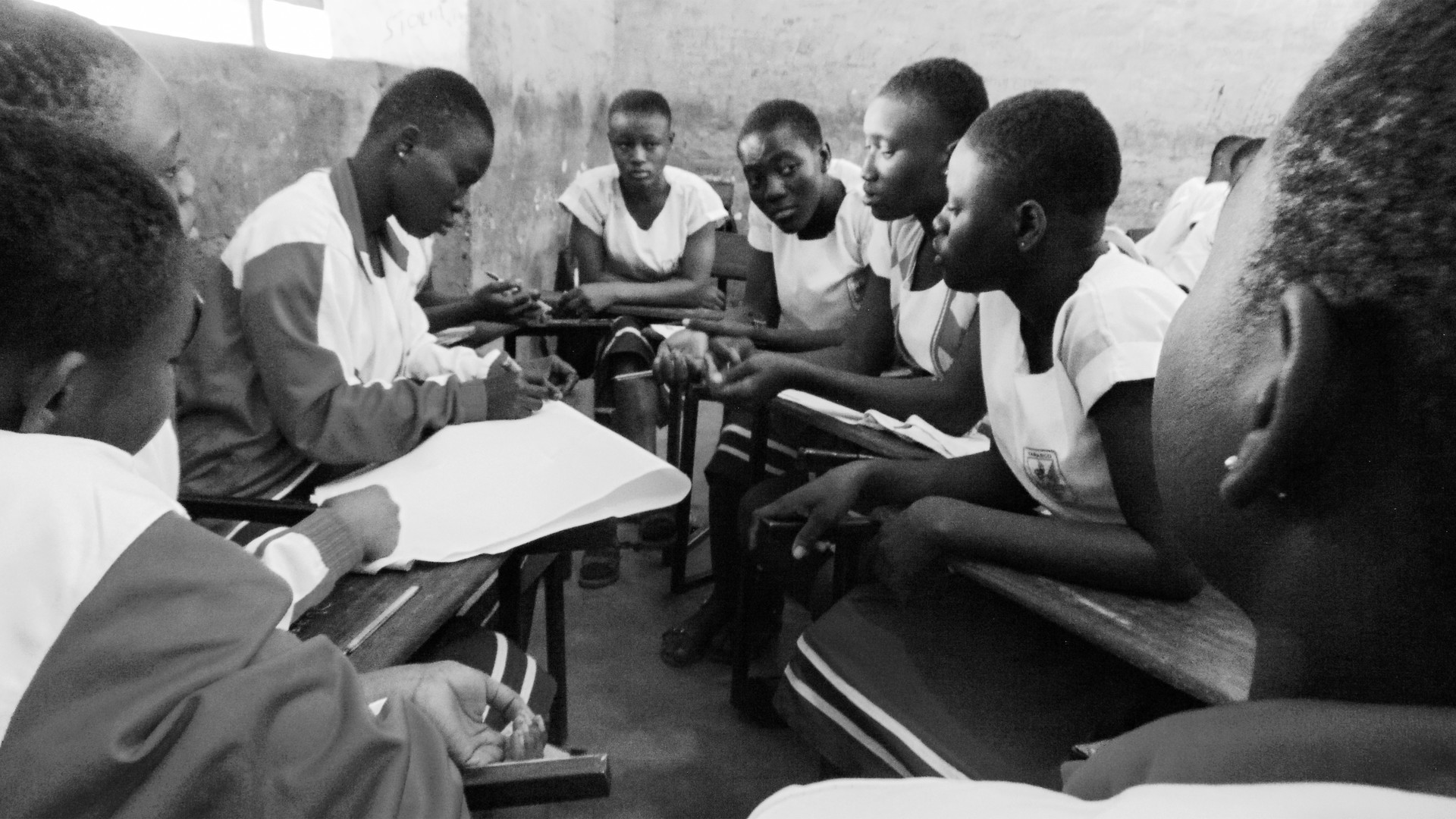

It used to take Matilda Meke-Banda six hours on her motorbike along dirt roads to reach two remote districts and deliver sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. In this part of southern Malawi, Machinga, family planning uptake is low, and the fertility rate, at 6.6, is the highest in the country. The Family Planning Association of Malawi, known as FPAM, runs a clinic in the town of Liwonde and it’s from here that Matilda travelled out six times a month. “We have established six watch groups, they are trained to address SRH issues in the community,” she explains. Luc Simon is the chair of one of those groups. “We teach about Family Planning,” he says. “We encourage parents and young people to go for HIV testing. We address forced early marriages, talk to parents and children to save a lot of young people.” And there are a lot of myths to dispel about family planning. Elizabeth Katunga is head of family planning in the district hospital in Machinga: “Family Planning is not very much accepted by the communities. Many women hide the use of contraceptives,” she says. “Injectables are most popular, easy to hide. We have cases here where husbands upon discovery of an implant take a knife and cut it out. It is not that people want big families per se but it is the misconceptions about contraceptives.” FPAM’s projects are based at the Youth Life clinic in Liwonde. The clinic offers integrated services: Family planning, HIV services, STI screening, cervical cancer screening and general healthcare (such as malaria). This joined-up approach has been effective says FPAM’s executive director Thoko Mbendera: “In government health facilities, you have different days, and long queues always, for family planning, for HIV, for general health, which is a challenge if the clinic is a 20 km walk away.There are privacy issues.” But now, FPAM’s services are being cut because of the Global Gag Rule (GGR), mobile clinics are grounded, and there are fears that much progress will be undone. Some of FPAM’s rural clients explain how the Watch Groups work in their community. “It starts with me as a man,” says group member George Mpemba. “We are examples on how to live with our wives. We are non-judgemental; we embark on a mutual learning process. Our meetings are not hearings, but a normal chat, there is laughing and talking. After the discussion we evaluate together and make an action plan.” Katherine, went to the group for help: “There was violence in my marriage; my husband forced himself on me even if I was tired from working in the field. When I complained there was trouble. He did not provide even the bedding. “He is a fisherman and he makes a lot of cash which he used to buy beer but nothing for us.I overheard a watch group meeting once and I realised there was a solution. They talked to him and made him realise that what he was doing was violence and against the law. It was ignorance.Things are better now, he brings money home, sex is consensual and sometimes he helps with household chores.”

| 16 April 2024

"We are non-judgemental; we embark on a mutual learning process."

It used to take Matilda Meke-Banda six hours on her motorbike along dirt roads to reach two remote districts and deliver sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. In this part of southern Malawi, Machinga, family planning uptake is low, and the fertility rate, at 6.6, is the highest in the country. The Family Planning Association of Malawi, known as FPAM, runs a clinic in the town of Liwonde and it’s from here that Matilda travelled out six times a month. “We have established six watch groups, they are trained to address SRH issues in the community,” she explains. Luc Simon is the chair of one of those groups. “We teach about Family Planning,” he says. “We encourage parents and young people to go for HIV testing. We address forced early marriages, talk to parents and children to save a lot of young people.” And there are a lot of myths to dispel about family planning. Elizabeth Katunga is head of family planning in the district hospital in Machinga: “Family Planning is not very much accepted by the communities. Many women hide the use of contraceptives,” she says. “Injectables are most popular, easy to hide. We have cases here where husbands upon discovery of an implant take a knife and cut it out. It is not that people want big families per se but it is the misconceptions about contraceptives.” FPAM’s projects are based at the Youth Life clinic in Liwonde. The clinic offers integrated services: Family planning, HIV services, STI screening, cervical cancer screening and general healthcare (such as malaria). This joined-up approach has been effective says FPAM’s executive director Thoko Mbendera: “In government health facilities, you have different days, and long queues always, for family planning, for HIV, for general health, which is a challenge if the clinic is a 20 km walk away.There are privacy issues.” But now, FPAM’s services are being cut because of the Global Gag Rule (GGR), mobile clinics are grounded, and there are fears that much progress will be undone. Some of FPAM’s rural clients explain how the Watch Groups work in their community. “It starts with me as a man,” says group member George Mpemba. “We are examples on how to live with our wives. We are non-judgemental; we embark on a mutual learning process. Our meetings are not hearings, but a normal chat, there is laughing and talking. After the discussion we evaluate together and make an action plan.” Katherine, went to the group for help: “There was violence in my marriage; my husband forced himself on me even if I was tired from working in the field. When I complained there was trouble. He did not provide even the bedding. “He is a fisherman and he makes a lot of cash which he used to buy beer but nothing for us.I overheard a watch group meeting once and I realised there was a solution. They talked to him and made him realise that what he was doing was violence and against the law. It was ignorance.Things are better now, he brings money home, sex is consensual and sometimes he helps with household chores.”

| 19 January 2018

“I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one"

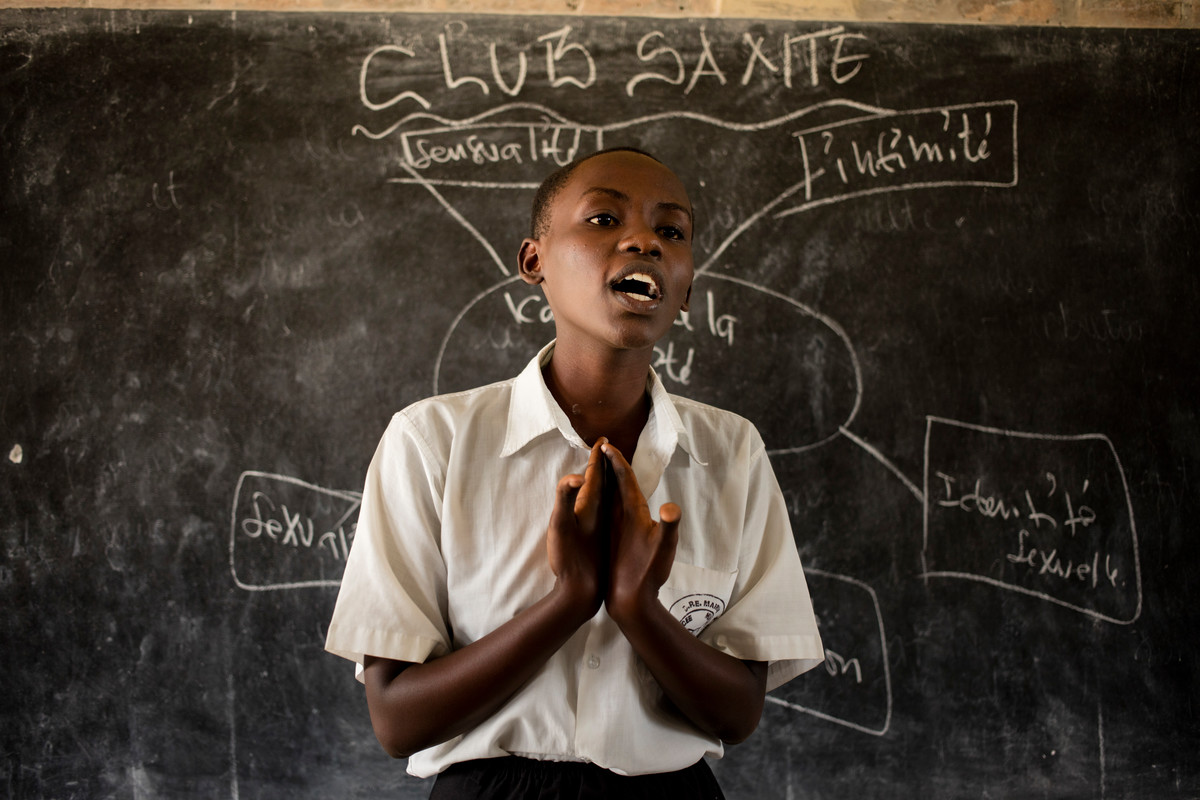

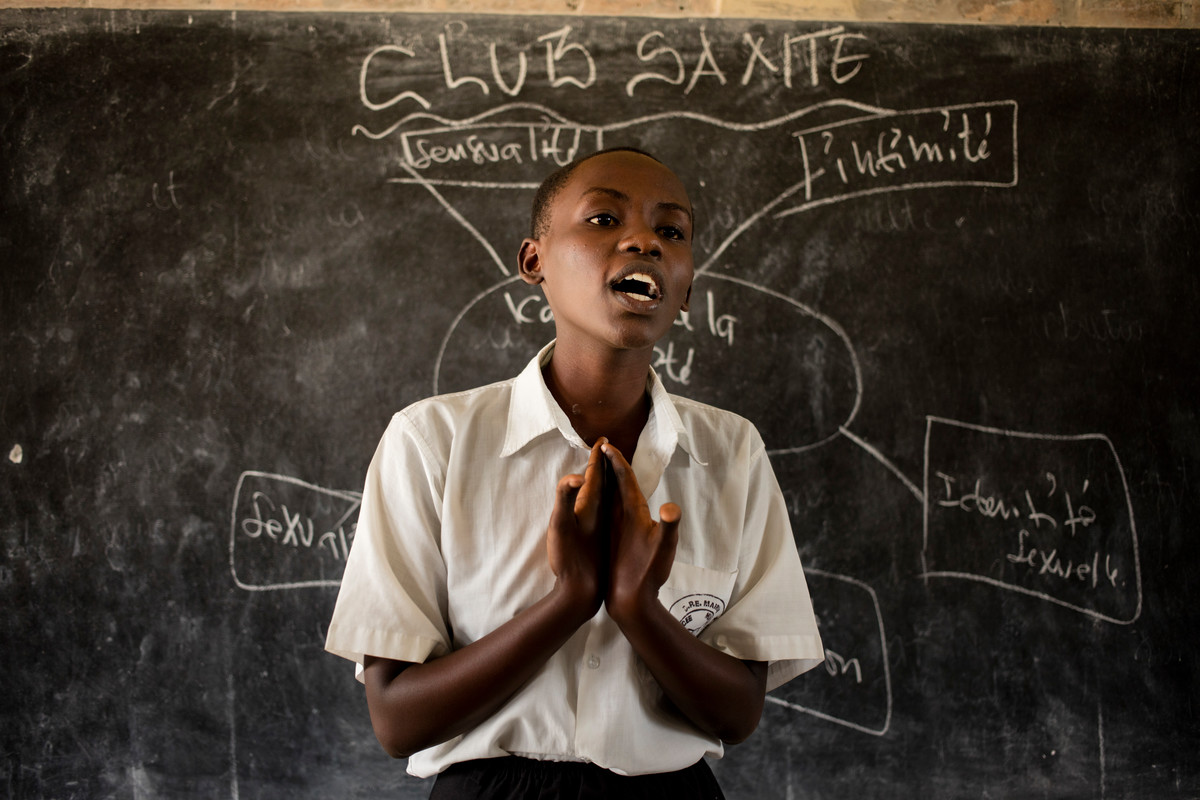

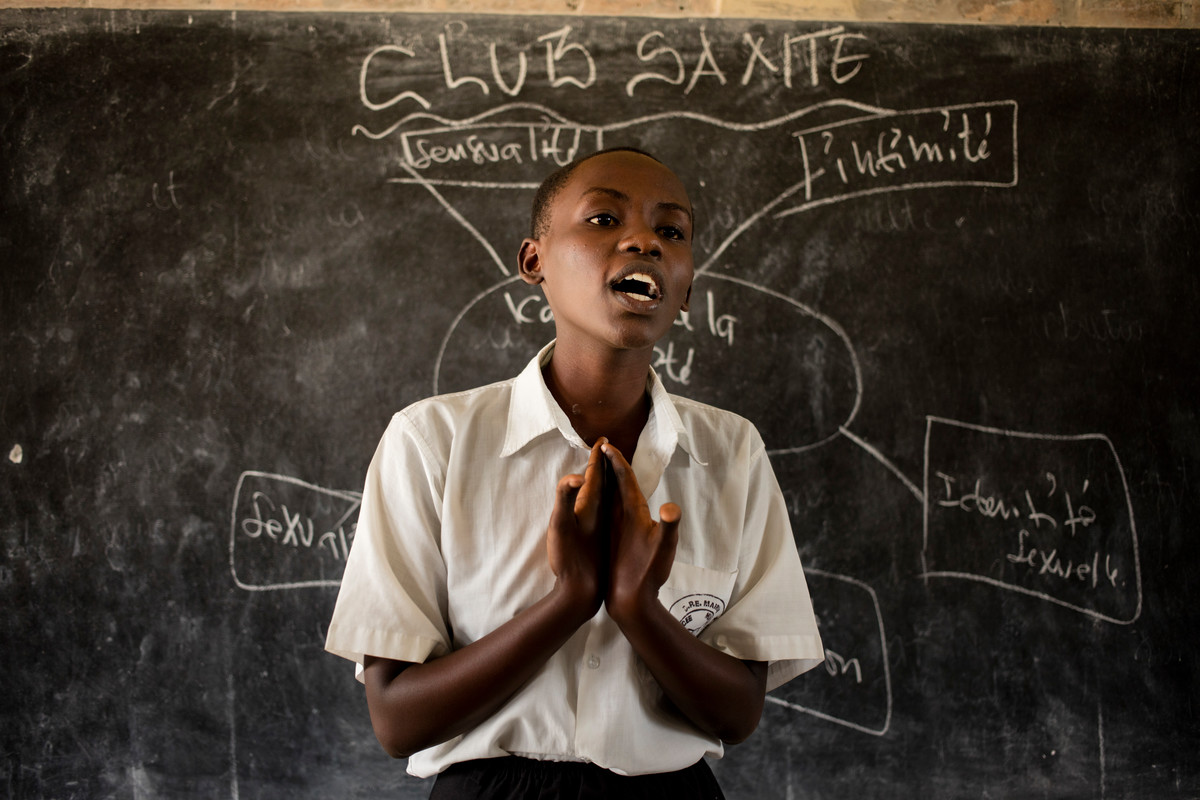

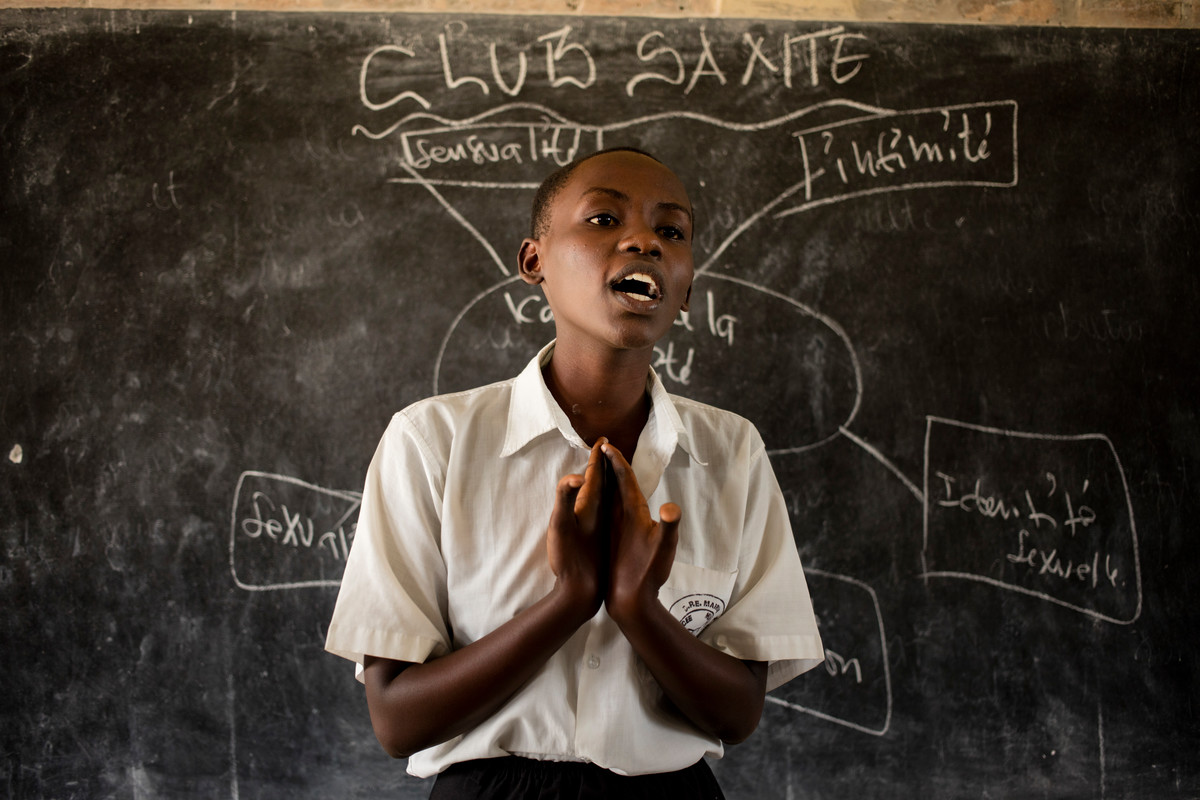

On Friday afternoon in Municipal Lycee of Nyakabiga, Burundi, headmistress Chantal Keza is introducing her students to the medical staff from Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ABUBEF). Peer educators at the school, trained by ABUBEF, will perform a short drama based around sexual health and will answer questions about contraception methods from students. One of the actresses is peer educator Ammande Berlyne Dushime. Ammande, who is 17 years old is one of three peer educators at the school. Ammande, together with her friends, perform their short drama on the stage based on a young girls quest for information on contraception. It ends on a positive note, with the girl receiving useful and correct information from a peer educator at her school. A story that could be a very real life scenario at her school. Peer programmes that trained Ammande, are under threat of closure due to the Global Gag rule. Ammande says, “I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one. I am ready to go on with work as peer educator, but if there are not going to be regular visits by the medical stuff from the clinic, then we will have no one to seek information and advice from. I am just a teenager, I know so little. Not only I will lose my support, but also I will not be taken serious by my schoolmates. With such important topic like sexual education and contraception, I am not the authority. I can only show the right way to go. And this road leads to ABUBEF.” She says “As peer educator I am responsible for Saturday morning meetings at the clinic. We sing songs, play games, have fun and learn new things about sex education, contraception, HIV protection and others. Visiting the clinic is then very easy, and no student has to be afraid, that showing up at the clinic that treats HIV positive people, will ruin their reputation. Now they know that we can meet there openly, and undercover of these meetings seek for help, information, professional advice and contraception methods” Peer educator classes are a safe and open place for students to openly talk about their sexual health. The Global Gage Rule will force peer educator programmes like this to close due to lack of funding. Help us bridge the funding gap Learn more about the Global Gag Rule

| 16 April 2024

“I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one"

On Friday afternoon in Municipal Lycee of Nyakabiga, Burundi, headmistress Chantal Keza is introducing her students to the medical staff from Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ABUBEF). Peer educators at the school, trained by ABUBEF, will perform a short drama based around sexual health and will answer questions about contraception methods from students. One of the actresses is peer educator Ammande Berlyne Dushime. Ammande, who is 17 years old is one of three peer educators at the school. Ammande, together with her friends, perform their short drama on the stage based on a young girls quest for information on contraception. It ends on a positive note, with the girl receiving useful and correct information from a peer educator at her school. A story that could be a very real life scenario at her school. Peer programmes that trained Ammande, are under threat of closure due to the Global Gag rule. Ammande says, “I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one. I am ready to go on with work as peer educator, but if there are not going to be regular visits by the medical stuff from the clinic, then we will have no one to seek information and advice from. I am just a teenager, I know so little. Not only I will lose my support, but also I will not be taken serious by my schoolmates. With such important topic like sexual education and contraception, I am not the authority. I can only show the right way to go. And this road leads to ABUBEF.” She says “As peer educator I am responsible for Saturday morning meetings at the clinic. We sing songs, play games, have fun and learn new things about sex education, contraception, HIV protection and others. Visiting the clinic is then very easy, and no student has to be afraid, that showing up at the clinic that treats HIV positive people, will ruin their reputation. Now they know that we can meet there openly, and undercover of these meetings seek for help, information, professional advice and contraception methods” Peer educator classes are a safe and open place for students to openly talk about their sexual health. The Global Gage Rule will force peer educator programmes like this to close due to lack of funding. Help us bridge the funding gap Learn more about the Global Gag Rule

| 22 January 2018

"We are non-judgemental; we embark on a mutual learning process."

It used to take Matilda Meke-Banda six hours on her motorbike along dirt roads to reach two remote districts and deliver sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. In this part of southern Malawi, Machinga, family planning uptake is low, and the fertility rate, at 6.6, is the highest in the country. The Family Planning Association of Malawi, known as FPAM, runs a clinic in the town of Liwonde and it’s from here that Matilda travelled out six times a month. “We have established six watch groups, they are trained to address SRH issues in the community,” she explains. Luc Simon is the chair of one of those groups. “We teach about Family Planning,” he says. “We encourage parents and young people to go for HIV testing. We address forced early marriages, talk to parents and children to save a lot of young people.” And there are a lot of myths to dispel about family planning. Elizabeth Katunga is head of family planning in the district hospital in Machinga: “Family Planning is not very much accepted by the communities. Many women hide the use of contraceptives,” she says. “Injectables are most popular, easy to hide. We have cases here where husbands upon discovery of an implant take a knife and cut it out. It is not that people want big families per se but it is the misconceptions about contraceptives.” FPAM’s projects are based at the Youth Life clinic in Liwonde. The clinic offers integrated services: Family planning, HIV services, STI screening, cervical cancer screening and general healthcare (such as malaria). This joined-up approach has been effective says FPAM’s executive director Thoko Mbendera: “In government health facilities, you have different days, and long queues always, for family planning, for HIV, for general health, which is a challenge if the clinic is a 20 km walk away.There are privacy issues.” But now, FPAM’s services are being cut because of the Global Gag Rule (GGR), mobile clinics are grounded, and there are fears that much progress will be undone. Some of FPAM’s rural clients explain how the Watch Groups work in their community. “It starts with me as a man,” says group member George Mpemba. “We are examples on how to live with our wives. We are non-judgemental; we embark on a mutual learning process. Our meetings are not hearings, but a normal chat, there is laughing and talking. After the discussion we evaluate together and make an action plan.” Katherine, went to the group for help: “There was violence in my marriage; my husband forced himself on me even if I was tired from working in the field. When I complained there was trouble. He did not provide even the bedding. “He is a fisherman and he makes a lot of cash which he used to buy beer but nothing for us.I overheard a watch group meeting once and I realised there was a solution. They talked to him and made him realise that what he was doing was violence and against the law. It was ignorance.Things are better now, he brings money home, sex is consensual and sometimes he helps with household chores.”

| 16 April 2024

"We are non-judgemental; we embark on a mutual learning process."

It used to take Matilda Meke-Banda six hours on her motorbike along dirt roads to reach two remote districts and deliver sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. In this part of southern Malawi, Machinga, family planning uptake is low, and the fertility rate, at 6.6, is the highest in the country. The Family Planning Association of Malawi, known as FPAM, runs a clinic in the town of Liwonde and it’s from here that Matilda travelled out six times a month. “We have established six watch groups, they are trained to address SRH issues in the community,” she explains. Luc Simon is the chair of one of those groups. “We teach about Family Planning,” he says. “We encourage parents and young people to go for HIV testing. We address forced early marriages, talk to parents and children to save a lot of young people.” And there are a lot of myths to dispel about family planning. Elizabeth Katunga is head of family planning in the district hospital in Machinga: “Family Planning is not very much accepted by the communities. Many women hide the use of contraceptives,” she says. “Injectables are most popular, easy to hide. We have cases here where husbands upon discovery of an implant take a knife and cut it out. It is not that people want big families per se but it is the misconceptions about contraceptives.” FPAM’s projects are based at the Youth Life clinic in Liwonde. The clinic offers integrated services: Family planning, HIV services, STI screening, cervical cancer screening and general healthcare (such as malaria). This joined-up approach has been effective says FPAM’s executive director Thoko Mbendera: “In government health facilities, you have different days, and long queues always, for family planning, for HIV, for general health, which is a challenge if the clinic is a 20 km walk away.There are privacy issues.” But now, FPAM’s services are being cut because of the Global Gag Rule (GGR), mobile clinics are grounded, and there are fears that much progress will be undone. Some of FPAM’s rural clients explain how the Watch Groups work in their community. “It starts with me as a man,” says group member George Mpemba. “We are examples on how to live with our wives. We are non-judgemental; we embark on a mutual learning process. Our meetings are not hearings, but a normal chat, there is laughing and talking. After the discussion we evaluate together and make an action plan.” Katherine, went to the group for help: “There was violence in my marriage; my husband forced himself on me even if I was tired from working in the field. When I complained there was trouble. He did not provide even the bedding. “He is a fisherman and he makes a lot of cash which he used to buy beer but nothing for us.I overheard a watch group meeting once and I realised there was a solution. They talked to him and made him realise that what he was doing was violence and against the law. It was ignorance.Things are better now, he brings money home, sex is consensual and sometimes he helps with household chores.”

| 19 January 2018

“I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one"

On Friday afternoon in Municipal Lycee of Nyakabiga, Burundi, headmistress Chantal Keza is introducing her students to the medical staff from Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ABUBEF). Peer educators at the school, trained by ABUBEF, will perform a short drama based around sexual health and will answer questions about contraception methods from students. One of the actresses is peer educator Ammande Berlyne Dushime. Ammande, who is 17 years old is one of three peer educators at the school. Ammande, together with her friends, perform their short drama on the stage based on a young girls quest for information on contraception. It ends on a positive note, with the girl receiving useful and correct information from a peer educator at her school. A story that could be a very real life scenario at her school. Peer programmes that trained Ammande, are under threat of closure due to the Global Gag rule. Ammande says, “I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one. I am ready to go on with work as peer educator, but if there are not going to be regular visits by the medical stuff from the clinic, then we will have no one to seek information and advice from. I am just a teenager, I know so little. Not only I will lose my support, but also I will not be taken serious by my schoolmates. With such important topic like sexual education and contraception, I am not the authority. I can only show the right way to go. And this road leads to ABUBEF.” She says “As peer educator I am responsible for Saturday morning meetings at the clinic. We sing songs, play games, have fun and learn new things about sex education, contraception, HIV protection and others. Visiting the clinic is then very easy, and no student has to be afraid, that showing up at the clinic that treats HIV positive people, will ruin their reputation. Now they know that we can meet there openly, and undercover of these meetings seek for help, information, professional advice and contraception methods” Peer educator classes are a safe and open place for students to openly talk about their sexual health. The Global Gage Rule will force peer educator programmes like this to close due to lack of funding. Help us bridge the funding gap Learn more about the Global Gag Rule

| 16 April 2024

“I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one"

On Friday afternoon in Municipal Lycee of Nyakabiga, Burundi, headmistress Chantal Keza is introducing her students to the medical staff from Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ABUBEF). Peer educators at the school, trained by ABUBEF, will perform a short drama based around sexual health and will answer questions about contraception methods from students. One of the actresses is peer educator Ammande Berlyne Dushime. Ammande, who is 17 years old is one of three peer educators at the school. Ammande, together with her friends, perform their short drama on the stage based on a young girls quest for information on contraception. It ends on a positive note, with the girl receiving useful and correct information from a peer educator at her school. A story that could be a very real life scenario at her school. Peer programmes that trained Ammande, are under threat of closure due to the Global Gag rule. Ammande says, “I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one. I am ready to go on with work as peer educator, but if there are not going to be regular visits by the medical stuff from the clinic, then we will have no one to seek information and advice from. I am just a teenager, I know so little. Not only I will lose my support, but also I will not be taken serious by my schoolmates. With such important topic like sexual education and contraception, I am not the authority. I can only show the right way to go. And this road leads to ABUBEF.” She says “As peer educator I am responsible for Saturday morning meetings at the clinic. We sing songs, play games, have fun and learn new things about sex education, contraception, HIV protection and others. Visiting the clinic is then very easy, and no student has to be afraid, that showing up at the clinic that treats HIV positive people, will ruin their reputation. Now they know that we can meet there openly, and undercover of these meetings seek for help, information, professional advice and contraception methods” Peer educator classes are a safe and open place for students to openly talk about their sexual health. The Global Gage Rule will force peer educator programmes like this to close due to lack of funding. Help us bridge the funding gap Learn more about the Global Gag Rule