Spotlight

A selection of stories from across the Federation

What does the year 2024 hold for us?

As the new year begins, we take a look at the trends and challenges ahead for sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Most Popular This Week

Palestine

In their own words: The people providing sexual and reproductive health care under bombardment in Gaza

Week after week, heavy Israeli bombardment from air, land, and sea, has continued across most of the Gaza Strip.

Vanuatu

When getting to the hospital is difficult, Vanuatu mobile outreach can save lives

In the mountains of Kumera on Tanna Island, Vanuatu, the village women of Kamahaul normally spend over 10,000 Vatu ($83 USD) to travel to the nearest hospital.

Vanuatu

Sex: changing minds and winning hearts in Tanna, Vanuatu

“Very traditional.” These two words are often used to describe the people of Tanna in Vanuatu, one of the most populated islands in the small country in the Pacific.

Vanuatu

Vanuatu cyclone response: The mental health toll on humanitarian providers

Girls and women from nearby villages flock to mobile health clinics set up by the Vanuatu Family Health Association (VFHA).

Cook Islands

Trans & Proud: Being Transgender in the Cook Islands

It’s a scene like many others around the world: a loving family pour over childhood photos, giggling and reminiscing about the memories.

Cook Islands

In Pictures: The activists who helped win LGBTI+ rights in the Cook Islands

The Cook Islands has removed a law that criminalizes homosexuality, in a huge victory for the local LGBTI+ community.

Cook Islands

Dean and the Cook Islands Condom Car

On the island of Rarotonga, the main island of the Cook Islands in the South Pacific, a little white van makes its rounds on the palm-tree lined circular road.

Filter our stories by:

- Associação Moçambicana para Desenvolvimento da Família

- Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial

- Association Malienne pour la Protection et la Promotion de la Famille

- Association Togolaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial

- Cameroon National Association for Family Welfare

- Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia

- Family Planning Association of Malawi

- Family Planning Association of Nepal

- Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka

- Foundation for the Promotion of Responsible Parenthood - Aruba

- Jamaica Family Planning Association

- Lesotho Planned Parenthood Association

- Palestinian Family Planning and Protection Association (PFPPA)

- Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana

- Planned Parenthood Federation of Nigeria

- Reproductive & Family Health Association of Fiji

- Reproductive Health Uganda

- Somaliland Family Health Association

- Tonga Family Health Association

- Vanuatu Family Health Association

| 11 March 2021

“FAMPLAN has made its mark”

Cultural barriers and stigma have threatened the work of the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN), but according to one senior healthcare provider at the Beth Jacobs Clinic in St Ann, Jamaica things have taken a positive turn, though some myths around contraceptive care seem to prevail. Committed to changing perceptions and attitudes Midwife, Dorothy, is head of maternal and child and sexual and reproductive healthcare at the Beth Jacobs Clinic and first began working with FAMPLAN in 1973. She says the organization has made its mark and reduced barriers and stigmatizing behaviour towards sexual health and contraceptive care. Cultural barriers were once often seen in families not equipped with basic knowledge about sexual health. “I remember some time ago a lady beat her daughter the first time she had her period as she believed the only way, she could see her period, is if a man had gone there [if the child was sexually active]. I had to send for her [mother] and have a session with both her and the child as to how a period works. She apologized to her daughter and said she was sorry. She never had the knowledge and she was happy for places like these where she could come and learn – both parent and child.” Working with religious groups to overcome stigma Religious groups once perpetuated stigma, so much so that women feared even walking near the FAMPLAN property. “Church women would hide and come, tell their husbands, partners or friend they are going to the doctor as they have a pain in their foot, which nuh guh suh [was not true]. Every minute you would see them looking to see if any church brother or sister came on the premises to see them as they would go back and tell the Minister because they don’t support family planning. But that was in the 90s.” Dorothy says that this has changed, and the church now participates in training sessions sexual healthcare and contraceptive choice, encouraging members to be informed about their wellbeing and reproductive rights. Navigating prevailing myths Yet despite the wealth of information and forward thinking of the communities the Beth Jacobs Clinic reaches, Dorothy says there are some prevailing myths, which if left unaddressed threaten to repeal the work of FAMPLAN. “Information sharing is important, and we try to have brochures on STIs, and issues around sexual and reproductive health and rights. But there are people who still believe sex with a virgin cures’ HIV, plus there are myths around contraceptive use too. We encourage reading. Back in the 70s, 80s, 90s we had a good library where we encouraged people to read, get books, get brochures. That is not so much now,” Dorothy says. Another challenge is ensuring women are consistent with accessing healthcare and contraception. “I saw a lady in the market who told me from the last day I did her pap smear she hasn’t done another one. That was five years ago. I had one recently - no pap smear for 14 years. I delivered her last child,” she says. Despite these challenges Dorothy remains dedicated and committed to her community knowing her work helps to improve women’s lives through choice. She is confident that the Mobile Unit with community-based distributors will be reintegrated into FAMPLAN healthcare delivery so that they can reach remote communities. “FAMPLAN has made its mark. It will never leave Jamaica or die.”

| 16 April 2024

“FAMPLAN has made its mark”

Cultural barriers and stigma have threatened the work of the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN), but according to one senior healthcare provider at the Beth Jacobs Clinic in St Ann, Jamaica things have taken a positive turn, though some myths around contraceptive care seem to prevail. Committed to changing perceptions and attitudes Midwife, Dorothy, is head of maternal and child and sexual and reproductive healthcare at the Beth Jacobs Clinic and first began working with FAMPLAN in 1973. She says the organization has made its mark and reduced barriers and stigmatizing behaviour towards sexual health and contraceptive care. Cultural barriers were once often seen in families not equipped with basic knowledge about sexual health. “I remember some time ago a lady beat her daughter the first time she had her period as she believed the only way, she could see her period, is if a man had gone there [if the child was sexually active]. I had to send for her [mother] and have a session with both her and the child as to how a period works. She apologized to her daughter and said she was sorry. She never had the knowledge and she was happy for places like these where she could come and learn – both parent and child.” Working with religious groups to overcome stigma Religious groups once perpetuated stigma, so much so that women feared even walking near the FAMPLAN property. “Church women would hide and come, tell their husbands, partners or friend they are going to the doctor as they have a pain in their foot, which nuh guh suh [was not true]. Every minute you would see them looking to see if any church brother or sister came on the premises to see them as they would go back and tell the Minister because they don’t support family planning. But that was in the 90s.” Dorothy says that this has changed, and the church now participates in training sessions sexual healthcare and contraceptive choice, encouraging members to be informed about their wellbeing and reproductive rights. Navigating prevailing myths Yet despite the wealth of information and forward thinking of the communities the Beth Jacobs Clinic reaches, Dorothy says there are some prevailing myths, which if left unaddressed threaten to repeal the work of FAMPLAN. “Information sharing is important, and we try to have brochures on STIs, and issues around sexual and reproductive health and rights. But there are people who still believe sex with a virgin cures’ HIV, plus there are myths around contraceptive use too. We encourage reading. Back in the 70s, 80s, 90s we had a good library where we encouraged people to read, get books, get brochures. That is not so much now,” Dorothy says. Another challenge is ensuring women are consistent with accessing healthcare and contraception. “I saw a lady in the market who told me from the last day I did her pap smear she hasn’t done another one. That was five years ago. I had one recently - no pap smear for 14 years. I delivered her last child,” she says. Despite these challenges Dorothy remains dedicated and committed to her community knowing her work helps to improve women’s lives through choice. She is confident that the Mobile Unit with community-based distributors will be reintegrated into FAMPLAN healthcare delivery so that they can reach remote communities. “FAMPLAN has made its mark. It will never leave Jamaica or die.”

| 11 March 2021

“This group is very dear to me”

Christan, 26, is committed to helping develop young people to become confident advocates for change. Christan is the executive assistant at the FAMPLAN Lenworth Jacobs Clinic. Her work overlaps with that of the Youth Action Movement (YAM), helping to foster the transitioning and development of youth into meaningful adults. Harnessing change through young advocates “FAMPLAN provides the space or capacity for young persons who they engage on a regular basis to grow — whether through outreach, rap sessions, educational sessions. The organization provides them with an opportunity to grow and build their capacity as it relates to advocating for sexual and reproductive health and rights amongst their other peers,” she said. Though she has passed on her youth officer baton, Christan, remains connected to YAM and ensures she leads by example. “When you have young adults, who are part of the organization, who lobby and advocate for the rights of other adults like themselves, then, on the other hand, you are going to have young people like Mario, Candice and Fiona who advocate for persons within their age cohort,” she said. “Transitioning out of the group and working alongside these young folks, I feel as if I can still share some of the realities they share, have one-on-one conversations with them, help them along their journey and also help myself as well, because social connectiveness is an important part of your mental health. This group is very, very, very dear to me.” Gaining confidence through volunteering With regards to its impact on her life, Christan said YAM helped her to become more of an extrovert and shaped her confidence. “I was more of an introvert and now I can get up do a wide presentation and engage other people without feeling like I do not have the capacity or expertise to bring across certain issues,” she said. However, she says that there is still a lot of sensitivity around sexual and reproductive health and rights. This can sometimes limit the conversations YAM is able to have and at times may generate fear among some of the group members. Turning members into advocates “There are certain sensitive topics that still present an issue when trying to bring it forward in certain spaces. Other challenges they [YAM members] may face are personal reservations. Although we provide them with the skillset, certain persons are still more reserved and are not able to be engaged in certain spaces. Sometimes they just want to stay in the back and issue flyers or something behind the scenes rather than being upfront.” But as the main aim of the movement is to develop advocates out of members, Christan’s conviction is helping to strengthen Yam's capacity. “To advocate you must be able to get up, stand up and speak for the persons who we classify as the voiceless or persons who are vulnerable and marginalised. I think that is one of the limitations as well. Going out and doing an HIV test and having counselling is OK, but as it relates to really standing up and advocating, being able to write a piece and send it to Parliament, being able to make certain submissions like editorial pieces. That needs to be strengthened,” says Christan.

| 16 April 2024

“This group is very dear to me”

Christan, 26, is committed to helping develop young people to become confident advocates for change. Christan is the executive assistant at the FAMPLAN Lenworth Jacobs Clinic. Her work overlaps with that of the Youth Action Movement (YAM), helping to foster the transitioning and development of youth into meaningful adults. Harnessing change through young advocates “FAMPLAN provides the space or capacity for young persons who they engage on a regular basis to grow — whether through outreach, rap sessions, educational sessions. The organization provides them with an opportunity to grow and build their capacity as it relates to advocating for sexual and reproductive health and rights amongst their other peers,” she said. Though she has passed on her youth officer baton, Christan, remains connected to YAM and ensures she leads by example. “When you have young adults, who are part of the organization, who lobby and advocate for the rights of other adults like themselves, then, on the other hand, you are going to have young people like Mario, Candice and Fiona who advocate for persons within their age cohort,” she said. “Transitioning out of the group and working alongside these young folks, I feel as if I can still share some of the realities they share, have one-on-one conversations with them, help them along their journey and also help myself as well, because social connectiveness is an important part of your mental health. This group is very, very, very dear to me.” Gaining confidence through volunteering With regards to its impact on her life, Christan said YAM helped her to become more of an extrovert and shaped her confidence. “I was more of an introvert and now I can get up do a wide presentation and engage other people without feeling like I do not have the capacity or expertise to bring across certain issues,” she said. However, she says that there is still a lot of sensitivity around sexual and reproductive health and rights. This can sometimes limit the conversations YAM is able to have and at times may generate fear among some of the group members. Turning members into advocates “There are certain sensitive topics that still present an issue when trying to bring it forward in certain spaces. Other challenges they [YAM members] may face are personal reservations. Although we provide them with the skillset, certain persons are still more reserved and are not able to be engaged in certain spaces. Sometimes they just want to stay in the back and issue flyers or something behind the scenes rather than being upfront.” But as the main aim of the movement is to develop advocates out of members, Christan’s conviction is helping to strengthen Yam's capacity. “To advocate you must be able to get up, stand up and speak for the persons who we classify as the voiceless or persons who are vulnerable and marginalised. I think that is one of the limitations as well. Going out and doing an HIV test and having counselling is OK, but as it relates to really standing up and advocating, being able to write a piece and send it to Parliament, being able to make certain submissions like editorial pieces. That needs to be strengthened,” says Christan.

| 14 January 2021

“Most NGOs don’t come here because it’s so hard to reach”

Dressed in a sparkling white medical coat, Alinafe runs one of Family Planning Association of Malawi (FPAM) mobile clinics in the village of Chigude. Under the hot midday sun, she patiently answering the questions of staff, volunteers and clients - all while heavily pregnant herself. Delivering care to remote communities “Most NGOs don’t come here because it’s so hard to reach,” she says, as women queue up in neat lines in front of two khaki tents to receive anything from a cervical cancer screening to abortion counselling. Without the mobile clinic, local women risk life-threatening health issues as a result of unsafe abortion or illnesses linked to undiagnosed HIV status. According to the Guttmacher Institute, complications from abortion are the cause of 6–18% of maternal deaths in Malawi. District Manager Alinafe joined the Family Planning Association of Malawi in 2016, when she was just 20 years old, after going to nursing school and getting her degree in public health. She was one of the team involved in the Linkages project, which provided free family planning care to sex workers in Mzuzu until it was discontinued following the 2017 Global Gag Rule. Seeing the impact of lost funding on care “This change has reduced our reach,” Alinafe says, explaining that before the Gag Rule they were reaching sex workers in all four traditional authorities in Mzimba North - now they mostly work in just one. She says this means they are “denying people services which are very important” and without reaching people with sexual and reproductive healthcare, increasing the risk of STIs. The reduction in healthcare has also led to a breakdown in the trust FPAM had worked to build in communities, gaining support from those in respected positions such as chiefs. “Important people in the communities have been complaining to us, saying why did you do this? You were here, these things were happening and our people were benefiting a lot but now nothing is good at all,” explains Alinafe. Still, she is determined to serve her community against the odds - running the outreach clinic funded by Global Affairs Canada five times a week, in four traditional authorities, as well as the FPAM Youth Life Centre in Mzuzu. “On a serious note, unsafe abortions are happening in this area at a very high rate,” says Alinafe at the FPAM clinic in Chigude. “Talking about abortions is a very important thing. Whether we like it or not, on-the-ground these things are really happening, so we can’t ignore them.”

| 16 April 2024

“Most NGOs don’t come here because it’s so hard to reach”

Dressed in a sparkling white medical coat, Alinafe runs one of Family Planning Association of Malawi (FPAM) mobile clinics in the village of Chigude. Under the hot midday sun, she patiently answering the questions of staff, volunteers and clients - all while heavily pregnant herself. Delivering care to remote communities “Most NGOs don’t come here because it’s so hard to reach,” she says, as women queue up in neat lines in front of two khaki tents to receive anything from a cervical cancer screening to abortion counselling. Without the mobile clinic, local women risk life-threatening health issues as a result of unsafe abortion or illnesses linked to undiagnosed HIV status. According to the Guttmacher Institute, complications from abortion are the cause of 6–18% of maternal deaths in Malawi. District Manager Alinafe joined the Family Planning Association of Malawi in 2016, when she was just 20 years old, after going to nursing school and getting her degree in public health. She was one of the team involved in the Linkages project, which provided free family planning care to sex workers in Mzuzu until it was discontinued following the 2017 Global Gag Rule. Seeing the impact of lost funding on care “This change has reduced our reach,” Alinafe says, explaining that before the Gag Rule they were reaching sex workers in all four traditional authorities in Mzimba North - now they mostly work in just one. She says this means they are “denying people services which are very important” and without reaching people with sexual and reproductive healthcare, increasing the risk of STIs. The reduction in healthcare has also led to a breakdown in the trust FPAM had worked to build in communities, gaining support from those in respected positions such as chiefs. “Important people in the communities have been complaining to us, saying why did you do this? You were here, these things were happening and our people were benefiting a lot but now nothing is good at all,” explains Alinafe. Still, she is determined to serve her community against the odds - running the outreach clinic funded by Global Affairs Canada five times a week, in four traditional authorities, as well as the FPAM Youth Life Centre in Mzuzu. “On a serious note, unsafe abortions are happening in this area at a very high rate,” says Alinafe at the FPAM clinic in Chigude. “Talking about abortions is a very important thing. Whether we like it or not, on-the-ground these things are really happening, so we can’t ignore them.”

| 14 January 2021

“I learnt about condoms and even female condoms"

Mary, a 30-year-old sex worker, happily drinks a beer at one of the bars she works at in downtown Lilongwe. Her grin is reflected in the entirely mirrored walls, lit with red and blue neon lights. Above her, a DJ sat in an elevated booth is playing pumping dancehall while a handful of people around the bar nod and dance along to the music. It’s not even midday yet. Mary got introduced to the Family Planning Association of Malawi through friends, who invited her to a training session for sex worker ‘peer educators’ on issues related to sexual and reproductive health and rights as part of the Linkages project. “I learnt about condoms and even female condoms, which I hadn’t heard of before,” remembers Mary. Life-changing care and support But the most life-changing care she received was an HIV test, where she learnt that she was positive and began anti-retroviral treatment (ART). “It was hard for me at first, but then I realized I had to start a new life,” says Mary, saying this included being open with her son about her status, who was 15 at the time. According to UNAIDS 2018 data, 9.2% of adult Malawians are living with HIV. Women and sex workers are disproportionately affected - the same year, 55% of sex workers were estimated to be living with HIV. Mary says she now feels much healthier and is open with her friends in the sex worker community about her status, also encouraging them to get tested for HIV. “Linkages brought us all closer together as we became open about these issues with each other,” remembers Mary. Looking out for other sex workers As a peer educator, Mary became a go-to person for other sex workers to turn to in cases of sexual assault. “I’ll receive a message from someone who has been assaulted, then call everyone together to discuss the issue, and we’d escort that person to report to police,” says Mary. During the Linkages project - which was impacted by the Global Gag Rule and abruptly discontinued in 2017 - Mary was given an allowance to travel to different ‘hotspot’ areas. In these bars and lodges, she explains in detail how she would go from room-to-room handing out male and female condoms and showing her peers how to use them. FPAM healthcare teams would also go directly to the hotspots reaching women with healthcare such as STI testing and abortion counselling. FPAM’s teams know how crucial it is to provide healthcare to their clients ensuring it is non-judgmental and confidential. This is a vital service: Mary says she has had four sex worker friends die as a result of unsafe abortions, and lack of knowledge about post-abortion care. “Since the project ended, most of us find it difficult to access these services,” says Mary, adding that “New sex workers don’t have the information I have, and without Linkages we’re not able to reach all the hotspot bars in Lilongwe to educate them.”

| 16 April 2024

“I learnt about condoms and even female condoms"

Mary, a 30-year-old sex worker, happily drinks a beer at one of the bars she works at in downtown Lilongwe. Her grin is reflected in the entirely mirrored walls, lit with red and blue neon lights. Above her, a DJ sat in an elevated booth is playing pumping dancehall while a handful of people around the bar nod and dance along to the music. It’s not even midday yet. Mary got introduced to the Family Planning Association of Malawi through friends, who invited her to a training session for sex worker ‘peer educators’ on issues related to sexual and reproductive health and rights as part of the Linkages project. “I learnt about condoms and even female condoms, which I hadn’t heard of before,” remembers Mary. Life-changing care and support But the most life-changing care she received was an HIV test, where she learnt that she was positive and began anti-retroviral treatment (ART). “It was hard for me at first, but then I realized I had to start a new life,” says Mary, saying this included being open with her son about her status, who was 15 at the time. According to UNAIDS 2018 data, 9.2% of adult Malawians are living with HIV. Women and sex workers are disproportionately affected - the same year, 55% of sex workers were estimated to be living with HIV. Mary says she now feels much healthier and is open with her friends in the sex worker community about her status, also encouraging them to get tested for HIV. “Linkages brought us all closer together as we became open about these issues with each other,” remembers Mary. Looking out for other sex workers As a peer educator, Mary became a go-to person for other sex workers to turn to in cases of sexual assault. “I’ll receive a message from someone who has been assaulted, then call everyone together to discuss the issue, and we’d escort that person to report to police,” says Mary. During the Linkages project - which was impacted by the Global Gag Rule and abruptly discontinued in 2017 - Mary was given an allowance to travel to different ‘hotspot’ areas. In these bars and lodges, she explains in detail how she would go from room-to-room handing out male and female condoms and showing her peers how to use them. FPAM healthcare teams would also go directly to the hotspots reaching women with healthcare such as STI testing and abortion counselling. FPAM’s teams know how crucial it is to provide healthcare to their clients ensuring it is non-judgmental and confidential. This is a vital service: Mary says she has had four sex worker friends die as a result of unsafe abortions, and lack of knowledge about post-abortion care. “Since the project ended, most of us find it difficult to access these services,” says Mary, adding that “New sex workers don’t have the information I have, and without Linkages we’re not able to reach all the hotspot bars in Lilongwe to educate them.”

| 08 January 2021

"Girls have to know their rights"

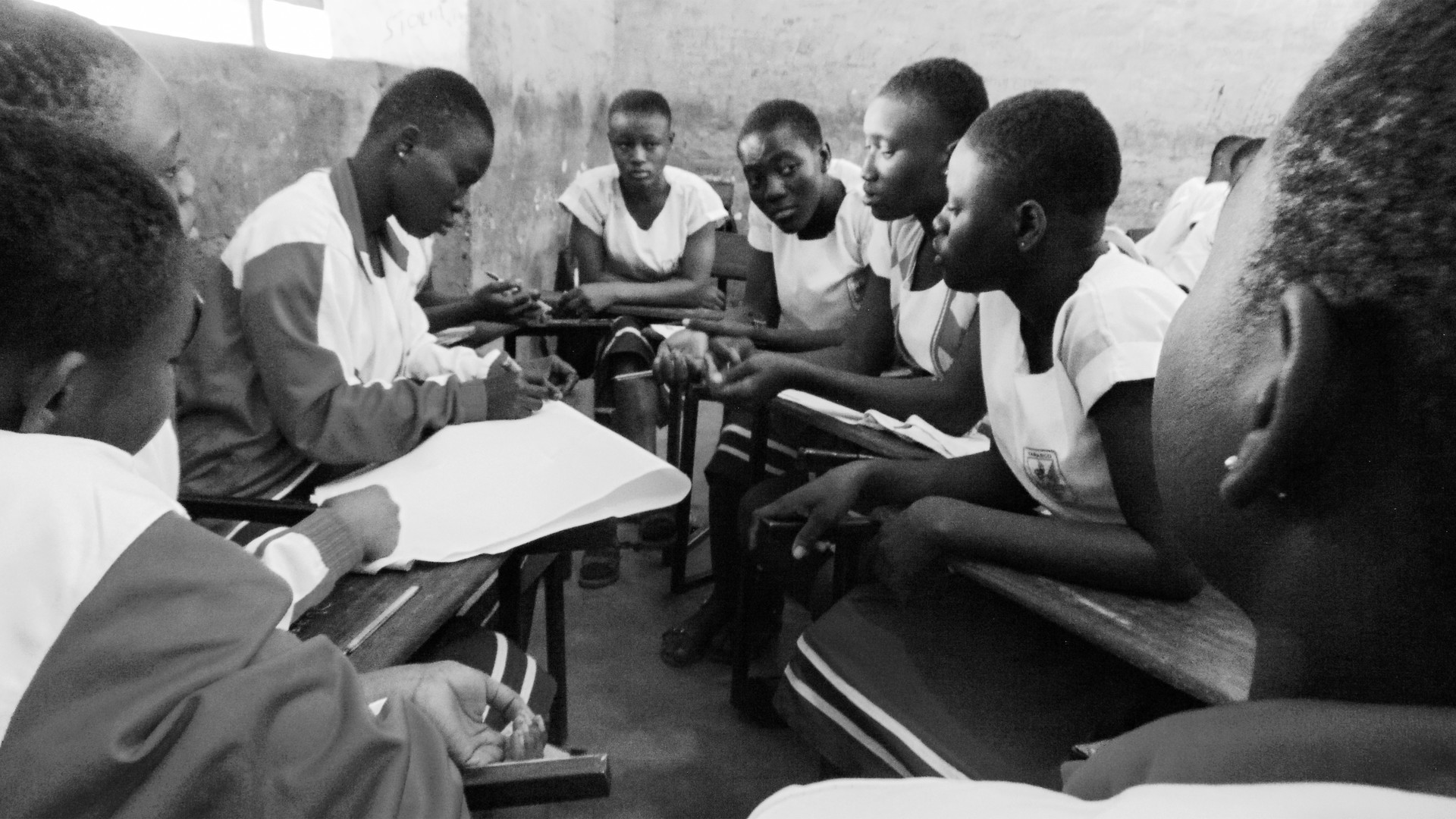

Aminata Sonogo listened intently to the group of young volunteers as they explained different types of contraception, and raised her hand with questions. Sitting at a wooden school desk at 22, Aminata is older than most of her classmates, but she shrugs off the looks and comments. She has fought hard to be here. Aminata is studying in Bamako, the capital of Mali. Just a quarter of Malian girls complete secondary school, according to UNICEF. But even if she will graduate later than most, Aminata is conscious of how far she has come. “I wanted to go to high school but I needed to pass some exams to get here. In the end, it took me three years,” she said. At the start of her final year of collège, or middle school, Aminata got pregnant. She is far from alone: 38% of Malian girls will be pregnant or a mother by the age of 18. Abortion is illegal in Mali except in cases of rape, incest or danger to the mother’s life, and even then it is difficult to obtain, according to medical professionals. Determined to take control of her life “I felt a lot of stigma from my classmates and even my teachers. I tried to ignore them and carry on going to school and studying. But I gave birth to my daughter just before my exams, so I couldn’t take them.” Aminata went through her pregnancy with little support, as the father of her daughter, Fatoumata, distanced himself from her after arguments about their situation. “I have had some problems with the father of the baby. We fought a lot and I didn’t see him for most of the pregnancy, right until the birth,” she recalled. The first year of her daughter’s life was a blur of doctors’ appointments, as Fatoumata was often ill. It seemed Aminata’s chances of finishing school were slipping away. But gradually her family began to take a more active role in caring for her daughter, and she began demanding more help from Fatoumata’s father too. She went back to school in the autumn, 18 months after Fatoumata’s birth and with more determination than ever. She no longer had time to hang out with friends after school, but attended classes, took care of her daughter and then studied more. At the end of the academic year, it paid off. “I did it. I passed my exams and now I am in high school,” Aminata said, smiling and relaxing her shoulders. "Family planning protects girls" Aminata’s next goal is her high school diploma, and obtaining it while trying to navigate the difficult world of relationships and sex. “It’s something you can talk about with your close friends. I would be too ashamed to talk about this with my parents,” she said. She is guided by visits from the young volunteers of the Association Malienne pour la Protection et Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), and shares her own story with classmates who she sees at risk. “The guys come up to you and tell you that you are beautiful, but if you don’t want to sleep with them they will rape you. That’s the choice. You can accept or you can refuse and they will rape you anyway,” she said. “Girls have to know their rights”. After listening to the volunteers talk about all the different options for contraception, she is reviewing her own choices. “Family planning protects girls,” Aminata said. “It means we can protect ourselves from pregnancies that we don’t want”.

| 16 April 2024

"Girls have to know their rights"

Aminata Sonogo listened intently to the group of young volunteers as they explained different types of contraception, and raised her hand with questions. Sitting at a wooden school desk at 22, Aminata is older than most of her classmates, but she shrugs off the looks and comments. She has fought hard to be here. Aminata is studying in Bamako, the capital of Mali. Just a quarter of Malian girls complete secondary school, according to UNICEF. But even if she will graduate later than most, Aminata is conscious of how far she has come. “I wanted to go to high school but I needed to pass some exams to get here. In the end, it took me three years,” she said. At the start of her final year of collège, or middle school, Aminata got pregnant. She is far from alone: 38% of Malian girls will be pregnant or a mother by the age of 18. Abortion is illegal in Mali except in cases of rape, incest or danger to the mother’s life, and even then it is difficult to obtain, according to medical professionals. Determined to take control of her life “I felt a lot of stigma from my classmates and even my teachers. I tried to ignore them and carry on going to school and studying. But I gave birth to my daughter just before my exams, so I couldn’t take them.” Aminata went through her pregnancy with little support, as the father of her daughter, Fatoumata, distanced himself from her after arguments about their situation. “I have had some problems with the father of the baby. We fought a lot and I didn’t see him for most of the pregnancy, right until the birth,” she recalled. The first year of her daughter’s life was a blur of doctors’ appointments, as Fatoumata was often ill. It seemed Aminata’s chances of finishing school were slipping away. But gradually her family began to take a more active role in caring for her daughter, and she began demanding more help from Fatoumata’s father too. She went back to school in the autumn, 18 months after Fatoumata’s birth and with more determination than ever. She no longer had time to hang out with friends after school, but attended classes, took care of her daughter and then studied more. At the end of the academic year, it paid off. “I did it. I passed my exams and now I am in high school,” Aminata said, smiling and relaxing her shoulders. "Family planning protects girls" Aminata’s next goal is her high school diploma, and obtaining it while trying to navigate the difficult world of relationships and sex. “It’s something you can talk about with your close friends. I would be too ashamed to talk about this with my parents,” she said. She is guided by visits from the young volunteers of the Association Malienne pour la Protection et Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), and shares her own story with classmates who she sees at risk. “The guys come up to you and tell you that you are beautiful, but if you don’t want to sleep with them they will rape you. That’s the choice. You can accept or you can refuse and they will rape you anyway,” she said. “Girls have to know their rights”. After listening to the volunteers talk about all the different options for contraception, she is reviewing her own choices. “Family planning protects girls,” Aminata said. “It means we can protect ourselves from pregnancies that we don’t want”.

| 08 January 2021

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 16 April 2024

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 11 March 2021

“FAMPLAN has made its mark”

Cultural barriers and stigma have threatened the work of the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN), but according to one senior healthcare provider at the Beth Jacobs Clinic in St Ann, Jamaica things have taken a positive turn, though some myths around contraceptive care seem to prevail. Committed to changing perceptions and attitudes Midwife, Dorothy, is head of maternal and child and sexual and reproductive healthcare at the Beth Jacobs Clinic and first began working with FAMPLAN in 1973. She says the organization has made its mark and reduced barriers and stigmatizing behaviour towards sexual health and contraceptive care. Cultural barriers were once often seen in families not equipped with basic knowledge about sexual health. “I remember some time ago a lady beat her daughter the first time she had her period as she believed the only way, she could see her period, is if a man had gone there [if the child was sexually active]. I had to send for her [mother] and have a session with both her and the child as to how a period works. She apologized to her daughter and said she was sorry. She never had the knowledge and she was happy for places like these where she could come and learn – both parent and child.” Working with religious groups to overcome stigma Religious groups once perpetuated stigma, so much so that women feared even walking near the FAMPLAN property. “Church women would hide and come, tell their husbands, partners or friend they are going to the doctor as they have a pain in their foot, which nuh guh suh [was not true]. Every minute you would see them looking to see if any church brother or sister came on the premises to see them as they would go back and tell the Minister because they don’t support family planning. But that was in the 90s.” Dorothy says that this has changed, and the church now participates in training sessions sexual healthcare and contraceptive choice, encouraging members to be informed about their wellbeing and reproductive rights. Navigating prevailing myths Yet despite the wealth of information and forward thinking of the communities the Beth Jacobs Clinic reaches, Dorothy says there are some prevailing myths, which if left unaddressed threaten to repeal the work of FAMPLAN. “Information sharing is important, and we try to have brochures on STIs, and issues around sexual and reproductive health and rights. But there are people who still believe sex with a virgin cures’ HIV, plus there are myths around contraceptive use too. We encourage reading. Back in the 70s, 80s, 90s we had a good library where we encouraged people to read, get books, get brochures. That is not so much now,” Dorothy says. Another challenge is ensuring women are consistent with accessing healthcare and contraception. “I saw a lady in the market who told me from the last day I did her pap smear she hasn’t done another one. That was five years ago. I had one recently - no pap smear for 14 years. I delivered her last child,” she says. Despite these challenges Dorothy remains dedicated and committed to her community knowing her work helps to improve women’s lives through choice. She is confident that the Mobile Unit with community-based distributors will be reintegrated into FAMPLAN healthcare delivery so that they can reach remote communities. “FAMPLAN has made its mark. It will never leave Jamaica or die.”

| 16 April 2024

“FAMPLAN has made its mark”

Cultural barriers and stigma have threatened the work of the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN), but according to one senior healthcare provider at the Beth Jacobs Clinic in St Ann, Jamaica things have taken a positive turn, though some myths around contraceptive care seem to prevail. Committed to changing perceptions and attitudes Midwife, Dorothy, is head of maternal and child and sexual and reproductive healthcare at the Beth Jacobs Clinic and first began working with FAMPLAN in 1973. She says the organization has made its mark and reduced barriers and stigmatizing behaviour towards sexual health and contraceptive care. Cultural barriers were once often seen in families not equipped with basic knowledge about sexual health. “I remember some time ago a lady beat her daughter the first time she had her period as she believed the only way, she could see her period, is if a man had gone there [if the child was sexually active]. I had to send for her [mother] and have a session with both her and the child as to how a period works. She apologized to her daughter and said she was sorry. She never had the knowledge and she was happy for places like these where she could come and learn – both parent and child.” Working with religious groups to overcome stigma Religious groups once perpetuated stigma, so much so that women feared even walking near the FAMPLAN property. “Church women would hide and come, tell their husbands, partners or friend they are going to the doctor as they have a pain in their foot, which nuh guh suh [was not true]. Every minute you would see them looking to see if any church brother or sister came on the premises to see them as they would go back and tell the Minister because they don’t support family planning. But that was in the 90s.” Dorothy says that this has changed, and the church now participates in training sessions sexual healthcare and contraceptive choice, encouraging members to be informed about their wellbeing and reproductive rights. Navigating prevailing myths Yet despite the wealth of information and forward thinking of the communities the Beth Jacobs Clinic reaches, Dorothy says there are some prevailing myths, which if left unaddressed threaten to repeal the work of FAMPLAN. “Information sharing is important, and we try to have brochures on STIs, and issues around sexual and reproductive health and rights. But there are people who still believe sex with a virgin cures’ HIV, plus there are myths around contraceptive use too. We encourage reading. Back in the 70s, 80s, 90s we had a good library where we encouraged people to read, get books, get brochures. That is not so much now,” Dorothy says. Another challenge is ensuring women are consistent with accessing healthcare and contraception. “I saw a lady in the market who told me from the last day I did her pap smear she hasn’t done another one. That was five years ago. I had one recently - no pap smear for 14 years. I delivered her last child,” she says. Despite these challenges Dorothy remains dedicated and committed to her community knowing her work helps to improve women’s lives through choice. She is confident that the Mobile Unit with community-based distributors will be reintegrated into FAMPLAN healthcare delivery so that they can reach remote communities. “FAMPLAN has made its mark. It will never leave Jamaica or die.”

| 11 March 2021

“This group is very dear to me”

Christan, 26, is committed to helping develop young people to become confident advocates for change. Christan is the executive assistant at the FAMPLAN Lenworth Jacobs Clinic. Her work overlaps with that of the Youth Action Movement (YAM), helping to foster the transitioning and development of youth into meaningful adults. Harnessing change through young advocates “FAMPLAN provides the space or capacity for young persons who they engage on a regular basis to grow — whether through outreach, rap sessions, educational sessions. The organization provides them with an opportunity to grow and build their capacity as it relates to advocating for sexual and reproductive health and rights amongst their other peers,” she said. Though she has passed on her youth officer baton, Christan, remains connected to YAM and ensures she leads by example. “When you have young adults, who are part of the organization, who lobby and advocate for the rights of other adults like themselves, then, on the other hand, you are going to have young people like Mario, Candice and Fiona who advocate for persons within their age cohort,” she said. “Transitioning out of the group and working alongside these young folks, I feel as if I can still share some of the realities they share, have one-on-one conversations with them, help them along their journey and also help myself as well, because social connectiveness is an important part of your mental health. This group is very, very, very dear to me.” Gaining confidence through volunteering With regards to its impact on her life, Christan said YAM helped her to become more of an extrovert and shaped her confidence. “I was more of an introvert and now I can get up do a wide presentation and engage other people without feeling like I do not have the capacity or expertise to bring across certain issues,” she said. However, she says that there is still a lot of sensitivity around sexual and reproductive health and rights. This can sometimes limit the conversations YAM is able to have and at times may generate fear among some of the group members. Turning members into advocates “There are certain sensitive topics that still present an issue when trying to bring it forward in certain spaces. Other challenges they [YAM members] may face are personal reservations. Although we provide them with the skillset, certain persons are still more reserved and are not able to be engaged in certain spaces. Sometimes they just want to stay in the back and issue flyers or something behind the scenes rather than being upfront.” But as the main aim of the movement is to develop advocates out of members, Christan’s conviction is helping to strengthen Yam's capacity. “To advocate you must be able to get up, stand up and speak for the persons who we classify as the voiceless or persons who are vulnerable and marginalised. I think that is one of the limitations as well. Going out and doing an HIV test and having counselling is OK, but as it relates to really standing up and advocating, being able to write a piece and send it to Parliament, being able to make certain submissions like editorial pieces. That needs to be strengthened,” says Christan.

| 16 April 2024

“This group is very dear to me”

Christan, 26, is committed to helping develop young people to become confident advocates for change. Christan is the executive assistant at the FAMPLAN Lenworth Jacobs Clinic. Her work overlaps with that of the Youth Action Movement (YAM), helping to foster the transitioning and development of youth into meaningful adults. Harnessing change through young advocates “FAMPLAN provides the space or capacity for young persons who they engage on a regular basis to grow — whether through outreach, rap sessions, educational sessions. The organization provides them with an opportunity to grow and build their capacity as it relates to advocating for sexual and reproductive health and rights amongst their other peers,” she said. Though she has passed on her youth officer baton, Christan, remains connected to YAM and ensures she leads by example. “When you have young adults, who are part of the organization, who lobby and advocate for the rights of other adults like themselves, then, on the other hand, you are going to have young people like Mario, Candice and Fiona who advocate for persons within their age cohort,” she said. “Transitioning out of the group and working alongside these young folks, I feel as if I can still share some of the realities they share, have one-on-one conversations with them, help them along their journey and also help myself as well, because social connectiveness is an important part of your mental health. This group is very, very, very dear to me.” Gaining confidence through volunteering With regards to its impact on her life, Christan said YAM helped her to become more of an extrovert and shaped her confidence. “I was more of an introvert and now I can get up do a wide presentation and engage other people without feeling like I do not have the capacity or expertise to bring across certain issues,” she said. However, she says that there is still a lot of sensitivity around sexual and reproductive health and rights. This can sometimes limit the conversations YAM is able to have and at times may generate fear among some of the group members. Turning members into advocates “There are certain sensitive topics that still present an issue when trying to bring it forward in certain spaces. Other challenges they [YAM members] may face are personal reservations. Although we provide them with the skillset, certain persons are still more reserved and are not able to be engaged in certain spaces. Sometimes they just want to stay in the back and issue flyers or something behind the scenes rather than being upfront.” But as the main aim of the movement is to develop advocates out of members, Christan’s conviction is helping to strengthen Yam's capacity. “To advocate you must be able to get up, stand up and speak for the persons who we classify as the voiceless or persons who are vulnerable and marginalised. I think that is one of the limitations as well. Going out and doing an HIV test and having counselling is OK, but as it relates to really standing up and advocating, being able to write a piece and send it to Parliament, being able to make certain submissions like editorial pieces. That needs to be strengthened,” says Christan.

| 14 January 2021

“Most NGOs don’t come here because it’s so hard to reach”

Dressed in a sparkling white medical coat, Alinafe runs one of Family Planning Association of Malawi (FPAM) mobile clinics in the village of Chigude. Under the hot midday sun, she patiently answering the questions of staff, volunteers and clients - all while heavily pregnant herself. Delivering care to remote communities “Most NGOs don’t come here because it’s so hard to reach,” she says, as women queue up in neat lines in front of two khaki tents to receive anything from a cervical cancer screening to abortion counselling. Without the mobile clinic, local women risk life-threatening health issues as a result of unsafe abortion or illnesses linked to undiagnosed HIV status. According to the Guttmacher Institute, complications from abortion are the cause of 6–18% of maternal deaths in Malawi. District Manager Alinafe joined the Family Planning Association of Malawi in 2016, when she was just 20 years old, after going to nursing school and getting her degree in public health. She was one of the team involved in the Linkages project, which provided free family planning care to sex workers in Mzuzu until it was discontinued following the 2017 Global Gag Rule. Seeing the impact of lost funding on care “This change has reduced our reach,” Alinafe says, explaining that before the Gag Rule they were reaching sex workers in all four traditional authorities in Mzimba North - now they mostly work in just one. She says this means they are “denying people services which are very important” and without reaching people with sexual and reproductive healthcare, increasing the risk of STIs. The reduction in healthcare has also led to a breakdown in the trust FPAM had worked to build in communities, gaining support from those in respected positions such as chiefs. “Important people in the communities have been complaining to us, saying why did you do this? You were here, these things were happening and our people were benefiting a lot but now nothing is good at all,” explains Alinafe. Still, she is determined to serve her community against the odds - running the outreach clinic funded by Global Affairs Canada five times a week, in four traditional authorities, as well as the FPAM Youth Life Centre in Mzuzu. “On a serious note, unsafe abortions are happening in this area at a very high rate,” says Alinafe at the FPAM clinic in Chigude. “Talking about abortions is a very important thing. Whether we like it or not, on-the-ground these things are really happening, so we can’t ignore them.”

| 16 April 2024

“Most NGOs don’t come here because it’s so hard to reach”

Dressed in a sparkling white medical coat, Alinafe runs one of Family Planning Association of Malawi (FPAM) mobile clinics in the village of Chigude. Under the hot midday sun, she patiently answering the questions of staff, volunteers and clients - all while heavily pregnant herself. Delivering care to remote communities “Most NGOs don’t come here because it’s so hard to reach,” she says, as women queue up in neat lines in front of two khaki tents to receive anything from a cervical cancer screening to abortion counselling. Without the mobile clinic, local women risk life-threatening health issues as a result of unsafe abortion or illnesses linked to undiagnosed HIV status. According to the Guttmacher Institute, complications from abortion are the cause of 6–18% of maternal deaths in Malawi. District Manager Alinafe joined the Family Planning Association of Malawi in 2016, when she was just 20 years old, after going to nursing school and getting her degree in public health. She was one of the team involved in the Linkages project, which provided free family planning care to sex workers in Mzuzu until it was discontinued following the 2017 Global Gag Rule. Seeing the impact of lost funding on care “This change has reduced our reach,” Alinafe says, explaining that before the Gag Rule they were reaching sex workers in all four traditional authorities in Mzimba North - now they mostly work in just one. She says this means they are “denying people services which are very important” and without reaching people with sexual and reproductive healthcare, increasing the risk of STIs. The reduction in healthcare has also led to a breakdown in the trust FPAM had worked to build in communities, gaining support from those in respected positions such as chiefs. “Important people in the communities have been complaining to us, saying why did you do this? You were here, these things were happening and our people were benefiting a lot but now nothing is good at all,” explains Alinafe. Still, she is determined to serve her community against the odds - running the outreach clinic funded by Global Affairs Canada five times a week, in four traditional authorities, as well as the FPAM Youth Life Centre in Mzuzu. “On a serious note, unsafe abortions are happening in this area at a very high rate,” says Alinafe at the FPAM clinic in Chigude. “Talking about abortions is a very important thing. Whether we like it or not, on-the-ground these things are really happening, so we can’t ignore them.”

| 14 January 2021

“I learnt about condoms and even female condoms"

Mary, a 30-year-old sex worker, happily drinks a beer at one of the bars she works at in downtown Lilongwe. Her grin is reflected in the entirely mirrored walls, lit with red and blue neon lights. Above her, a DJ sat in an elevated booth is playing pumping dancehall while a handful of people around the bar nod and dance along to the music. It’s not even midday yet. Mary got introduced to the Family Planning Association of Malawi through friends, who invited her to a training session for sex worker ‘peer educators’ on issues related to sexual and reproductive health and rights as part of the Linkages project. “I learnt about condoms and even female condoms, which I hadn’t heard of before,” remembers Mary. Life-changing care and support But the most life-changing care she received was an HIV test, where she learnt that she was positive and began anti-retroviral treatment (ART). “It was hard for me at first, but then I realized I had to start a new life,” says Mary, saying this included being open with her son about her status, who was 15 at the time. According to UNAIDS 2018 data, 9.2% of adult Malawians are living with HIV. Women and sex workers are disproportionately affected - the same year, 55% of sex workers were estimated to be living with HIV. Mary says she now feels much healthier and is open with her friends in the sex worker community about her status, also encouraging them to get tested for HIV. “Linkages brought us all closer together as we became open about these issues with each other,” remembers Mary. Looking out for other sex workers As a peer educator, Mary became a go-to person for other sex workers to turn to in cases of sexual assault. “I’ll receive a message from someone who has been assaulted, then call everyone together to discuss the issue, and we’d escort that person to report to police,” says Mary. During the Linkages project - which was impacted by the Global Gag Rule and abruptly discontinued in 2017 - Mary was given an allowance to travel to different ‘hotspot’ areas. In these bars and lodges, she explains in detail how she would go from room-to-room handing out male and female condoms and showing her peers how to use them. FPAM healthcare teams would also go directly to the hotspots reaching women with healthcare such as STI testing and abortion counselling. FPAM’s teams know how crucial it is to provide healthcare to their clients ensuring it is non-judgmental and confidential. This is a vital service: Mary says she has had four sex worker friends die as a result of unsafe abortions, and lack of knowledge about post-abortion care. “Since the project ended, most of us find it difficult to access these services,” says Mary, adding that “New sex workers don’t have the information I have, and without Linkages we’re not able to reach all the hotspot bars in Lilongwe to educate them.”

| 16 April 2024

“I learnt about condoms and even female condoms"

Mary, a 30-year-old sex worker, happily drinks a beer at one of the bars she works at in downtown Lilongwe. Her grin is reflected in the entirely mirrored walls, lit with red and blue neon lights. Above her, a DJ sat in an elevated booth is playing pumping dancehall while a handful of people around the bar nod and dance along to the music. It’s not even midday yet. Mary got introduced to the Family Planning Association of Malawi through friends, who invited her to a training session for sex worker ‘peer educators’ on issues related to sexual and reproductive health and rights as part of the Linkages project. “I learnt about condoms and even female condoms, which I hadn’t heard of before,” remembers Mary. Life-changing care and support But the most life-changing care she received was an HIV test, where she learnt that she was positive and began anti-retroviral treatment (ART). “It was hard for me at first, but then I realized I had to start a new life,” says Mary, saying this included being open with her son about her status, who was 15 at the time. According to UNAIDS 2018 data, 9.2% of adult Malawians are living with HIV. Women and sex workers are disproportionately affected - the same year, 55% of sex workers were estimated to be living with HIV. Mary says she now feels much healthier and is open with her friends in the sex worker community about her status, also encouraging them to get tested for HIV. “Linkages brought us all closer together as we became open about these issues with each other,” remembers Mary. Looking out for other sex workers As a peer educator, Mary became a go-to person for other sex workers to turn to in cases of sexual assault. “I’ll receive a message from someone who has been assaulted, then call everyone together to discuss the issue, and we’d escort that person to report to police,” says Mary. During the Linkages project - which was impacted by the Global Gag Rule and abruptly discontinued in 2017 - Mary was given an allowance to travel to different ‘hotspot’ areas. In these bars and lodges, she explains in detail how she would go from room-to-room handing out male and female condoms and showing her peers how to use them. FPAM healthcare teams would also go directly to the hotspots reaching women with healthcare such as STI testing and abortion counselling. FPAM’s teams know how crucial it is to provide healthcare to their clients ensuring it is non-judgmental and confidential. This is a vital service: Mary says she has had four sex worker friends die as a result of unsafe abortions, and lack of knowledge about post-abortion care. “Since the project ended, most of us find it difficult to access these services,” says Mary, adding that “New sex workers don’t have the information I have, and without Linkages we’re not able to reach all the hotspot bars in Lilongwe to educate them.”

| 08 January 2021

"Girls have to know their rights"

Aminata Sonogo listened intently to the group of young volunteers as they explained different types of contraception, and raised her hand with questions. Sitting at a wooden school desk at 22, Aminata is older than most of her classmates, but she shrugs off the looks and comments. She has fought hard to be here. Aminata is studying in Bamako, the capital of Mali. Just a quarter of Malian girls complete secondary school, according to UNICEF. But even if she will graduate later than most, Aminata is conscious of how far she has come. “I wanted to go to high school but I needed to pass some exams to get here. In the end, it took me three years,” she said. At the start of her final year of collège, or middle school, Aminata got pregnant. She is far from alone: 38% of Malian girls will be pregnant or a mother by the age of 18. Abortion is illegal in Mali except in cases of rape, incest or danger to the mother’s life, and even then it is difficult to obtain, according to medical professionals. Determined to take control of her life “I felt a lot of stigma from my classmates and even my teachers. I tried to ignore them and carry on going to school and studying. But I gave birth to my daughter just before my exams, so I couldn’t take them.” Aminata went through her pregnancy with little support, as the father of her daughter, Fatoumata, distanced himself from her after arguments about their situation. “I have had some problems with the father of the baby. We fought a lot and I didn’t see him for most of the pregnancy, right until the birth,” she recalled. The first year of her daughter’s life was a blur of doctors’ appointments, as Fatoumata was often ill. It seemed Aminata’s chances of finishing school were slipping away. But gradually her family began to take a more active role in caring for her daughter, and she began demanding more help from Fatoumata’s father too. She went back to school in the autumn, 18 months after Fatoumata’s birth and with more determination than ever. She no longer had time to hang out with friends after school, but attended classes, took care of her daughter and then studied more. At the end of the academic year, it paid off. “I did it. I passed my exams and now I am in high school,” Aminata said, smiling and relaxing her shoulders. "Family planning protects girls" Aminata’s next goal is her high school diploma, and obtaining it while trying to navigate the difficult world of relationships and sex. “It’s something you can talk about with your close friends. I would be too ashamed to talk about this with my parents,” she said. She is guided by visits from the young volunteers of the Association Malienne pour la Protection et Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), and shares her own story with classmates who she sees at risk. “The guys come up to you and tell you that you are beautiful, but if you don’t want to sleep with them they will rape you. That’s the choice. You can accept or you can refuse and they will rape you anyway,” she said. “Girls have to know their rights”. After listening to the volunteers talk about all the different options for contraception, she is reviewing her own choices. “Family planning protects girls,” Aminata said. “It means we can protect ourselves from pregnancies that we don’t want”.

| 16 April 2024

"Girls have to know their rights"

Aminata Sonogo listened intently to the group of young volunteers as they explained different types of contraception, and raised her hand with questions. Sitting at a wooden school desk at 22, Aminata is older than most of her classmates, but she shrugs off the looks and comments. She has fought hard to be here. Aminata is studying in Bamako, the capital of Mali. Just a quarter of Malian girls complete secondary school, according to UNICEF. But even if she will graduate later than most, Aminata is conscious of how far she has come. “I wanted to go to high school but I needed to pass some exams to get here. In the end, it took me three years,” she said. At the start of her final year of collège, or middle school, Aminata got pregnant. She is far from alone: 38% of Malian girls will be pregnant or a mother by the age of 18. Abortion is illegal in Mali except in cases of rape, incest or danger to the mother’s life, and even then it is difficult to obtain, according to medical professionals. Determined to take control of her life “I felt a lot of stigma from my classmates and even my teachers. I tried to ignore them and carry on going to school and studying. But I gave birth to my daughter just before my exams, so I couldn’t take them.” Aminata went through her pregnancy with little support, as the father of her daughter, Fatoumata, distanced himself from her after arguments about their situation. “I have had some problems with the father of the baby. We fought a lot and I didn’t see him for most of the pregnancy, right until the birth,” she recalled. The first year of her daughter’s life was a blur of doctors’ appointments, as Fatoumata was often ill. It seemed Aminata’s chances of finishing school were slipping away. But gradually her family began to take a more active role in caring for her daughter, and she began demanding more help from Fatoumata’s father too. She went back to school in the autumn, 18 months after Fatoumata’s birth and with more determination than ever. She no longer had time to hang out with friends after school, but attended classes, took care of her daughter and then studied more. At the end of the academic year, it paid off. “I did it. I passed my exams and now I am in high school,” Aminata said, smiling and relaxing her shoulders. "Family planning protects girls" Aminata’s next goal is her high school diploma, and obtaining it while trying to navigate the difficult world of relationships and sex. “It’s something you can talk about with your close friends. I would be too ashamed to talk about this with my parents,” she said. She is guided by visits from the young volunteers of the Association Malienne pour la Protection et Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), and shares her own story with classmates who she sees at risk. “The guys come up to you and tell you that you are beautiful, but if you don’t want to sleep with them they will rape you. That’s the choice. You can accept or you can refuse and they will rape you anyway,” she said. “Girls have to know their rights”. After listening to the volunteers talk about all the different options for contraception, she is reviewing her own choices. “Family planning protects girls,” Aminata said. “It means we can protect ourselves from pregnancies that we don’t want”.

| 08 January 2021

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 16 April 2024

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.