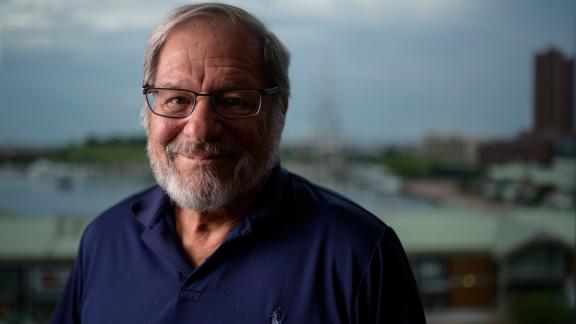

Steven Sinding remembers, pretty much to the day, when he became fascinated with population studies. He was a senior in college, and concern about global population growth was just starting to emerge. “Population was a hot topic in the ‘60s and ‘70s,” he says.

One of his favorite professors, Robert Neil, gave a lecture called the Mushroom Crowd. “It really captured my imagination,” he says. “It was a pivotal moment in my career.”

Decades later, Sinding has retired from a storied career as a population expert that took him from the US Agency for International Development to the World Bank to the Rockefeller Foundation to Columbia University, and eventually to become Director-General of the International Planned Parenthood Federation.

A lot has happened since Sinding started out. Decades ago, population was a different conversation, with policies focused chiefly on addressing high fertility rates and reducing population growth rates — in some cases by “inundating” communities with contraceptive supplies. The 1980’s, Sinding says, were marked by coercive policies in a few countries, particularly in Asia, aimed at forcing down birth rates, like one-child policy and coerced sterilization.

“But the field began to change as reproductive rights groups began to insist that programs be more holistic, addressing the needs of women much more broadly than just family planning.” To some, “family planning became a dirty word,” denoting a top-down approach to reducing population growth he says.

Then came 1994, and the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, which will mark its 25th anniversary in November. As a member of the US delegation in Cairo, Sinding helped set the agenda for the conference’s culminating document: the ICPD Programme of Action (PoA).

A major shift

The landmark UN conference marked a major shift in thinking about reproductive health and rights – not as a population control issue, but as a human rights issue. “From that time onward working in the population field meant really working in the field of women’s rights, reproductive rights, and broader approaches to addressing high fertility.

“What made the Cairo conference so exciting is that it put population in the context of a larger conversation in which the most basic human rights issues were addressed. One talked in Cairo about population as it was affected by educational policy and education programs, laws affecting the role of women in society, and gender relationships.”

Although Cairo changed the whole approach to population, it also came at the end of an era of remarkable achievements, Sinding says. At the beginning of Sinding’s career, the average fertility rate in the global south was 6.5 children—today it’s about 2.4. “That’s a revolutionary change in human behavior,” he says. But the top-down approach to programs and policies needed to change, he says.

Cairo homed in on the rights of adolescents and young people to reproductive health services, on male responsibility, and shifted focus away from coercive methods towards addressing the issue through programs that empower individuals. That was one of the most important changes that came out of Cairo.

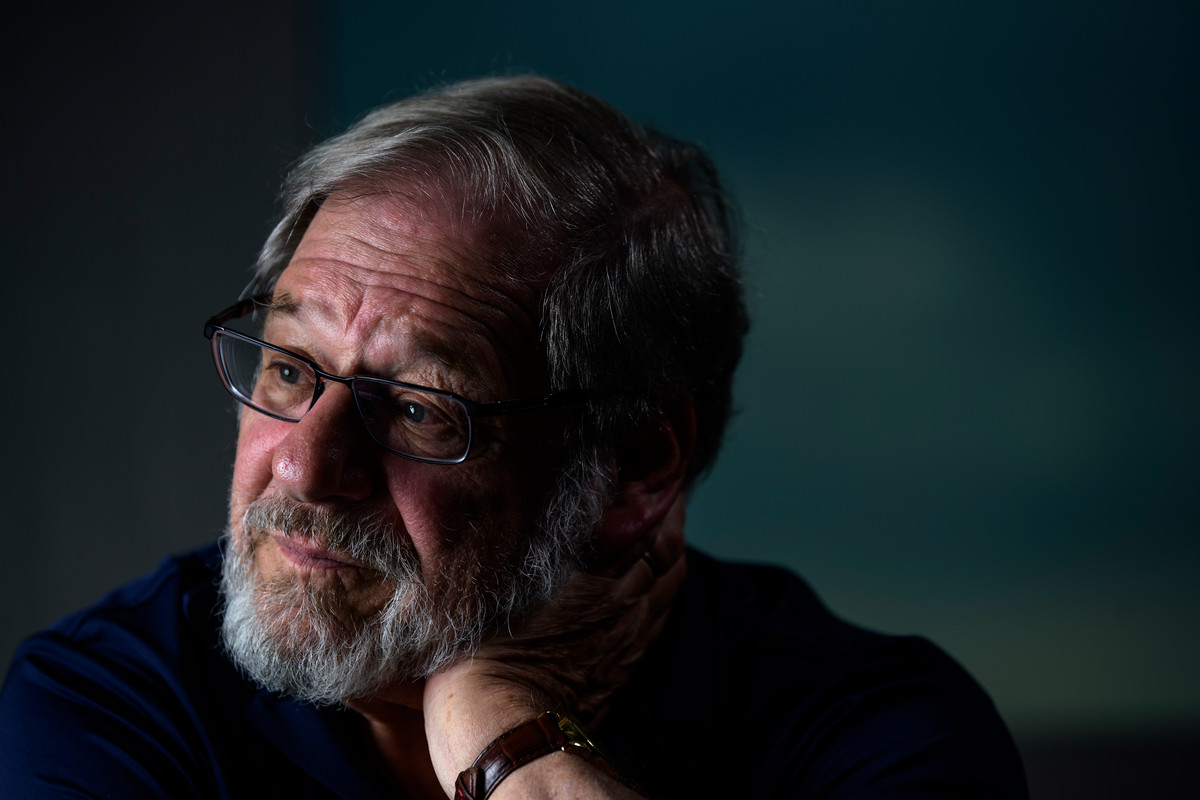

Despite Cairo’s achievements, it wasn’t without controversy, even for those who signed on to the Programme of Action. Is Sinding completely happy with the outcome? “No.”

“The Cairo conference — in my opinion — represented something of an overreaction to those coercive programs of the 1970s and ‘80s, but an understandable reaction.”

“While I think to say that the only thing that mattered was getting contraceptives into villages was wrong, it was equally wrong to say that the only thing that mattered was everything else. Strong voluntary family planning programs needed to be endorsed, but they weren’t. I think that what came out of Cairo was not sufficiently balanced.”

While a consensus was reached, the Programme of Action manifested very differently from country to country. In Europe, for example, broad access to reproductive healthcare had taken hold long before Cairo. But elsewhere after the conference, delegations returned home to discover that “politicians and theologians in their countries weren’t ready to go as far as the Programme of Action called for.”

A pushback since Cairo

In the years since Cairo, “There has been pushback against liberalism in general and the rights focus.” So much so, Sinding says, that his colleagues in the field have elected numerous times to not revisit the PoA, concerned that doing so could actually roll back important elements of it. “That suggests to me that since Cairo the community of nations has diminished in its commitment to what Cairo stands for.”

That spirit was largely defined by the dogged efforts of progressive feminist groups who brought an “extraordinarily well organized” voice that proved deeply influential at Cairo, resulting in a PoA that made a statement” that was ahead of its time, and may still be today. “The Cairo PoA was a remarkably progressive document, containing many goals that remain elusive still today and that represent an important unfinished agenda for the future,” he says.

And how did Cairo unite 179 nations under such a progressive agenda? Sinding refers to a Margaret Mead quote that he and his wife both love: “Don’t underestimate the importance of small groups of people changing the world. In fact, it’s the only thing that ever has,” he recites. “I think about that quote often when I think about what happened at Cairo.”

when