In Bangladesh menstrual regulation, the method of establishing non-pregnancy for a woman at risk of unintended pregnancy, has been a part of the country’s family planning program since 1979 and is allowed up to 10 –12 weeks after a woman’s last menstrual period. There are no legal restrictions on providing post-abortion care.

Dhukuriabera Family Health & Welfare Centre is prone to flooding during rainy season in Bangladesh. The watermarks on the walls of the clinic from last year’s flood almost reach the ceiling, and serve as a reminder of the extreme circumstances staff at the centre face in providing vital healthcare during a humanitarian crisis.

“Our office was flooded. We had to stand on chairs,” says Salma Parvin, a staff member of the centre, pointing to mildew marks on the walls. “Very few patients came to access services.”

“During floods there are lots of challenges,” says Dr. Laila Arjumand Banu at the Belkuchi Upazila Health & Family Planning Complex. “People get stuck and may forget to use the normal family planning methods.”

The inability to access medical centres during floods can have other repercussions.

“[When there are floods] clients sometimes have a procedure done by a village provider and thereafter come to us with complications,” says nursing supervisor Lovely Yasmin. “And then we have to provide services with [medical equipment] that we don’t have.”

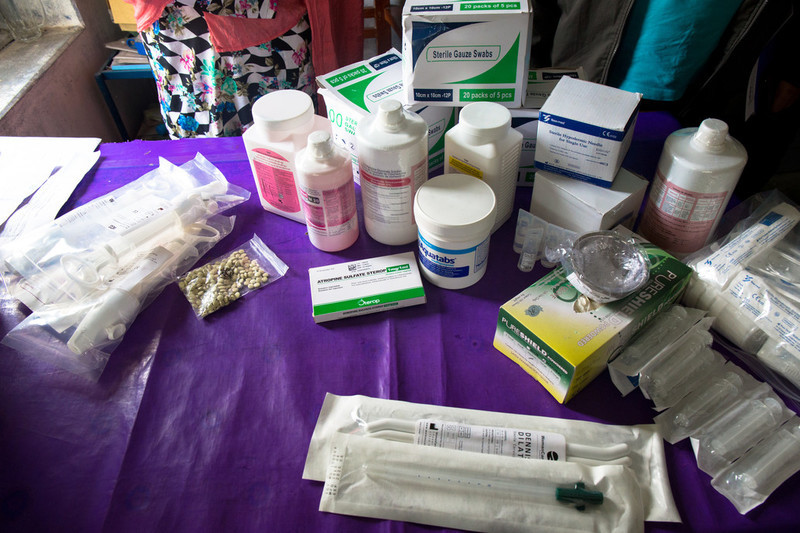

As part of their Innovation Programme project, IPPF’s South Asia office the IPPF South Asia office in collaboration with the University of Leicester and the Government of Bangladesh have has begun distributing UNFPA’s reproductive health kit 8 in strategic locations most prone to seasonal flooding. Kit 8 contains three months’ worth of medicine and equipment for the management of miscarriage and complications of unsafe abortion in emergency situations, essential to minimize associated morbidity and mortality.

“I find the kits very useful,” says nurse Lipara Khatun. “Patients will benefit as they can avail these services closer to home and not have to come all the way to centres.”

At her home in the village of Charmokimpur, Bijli Khatun, 32, explains how flooding was just one of many challenges her unplanned pregnancy presented. “One of [my] children is disabled and so the fear of possibly another disabled child was scary,” Bijli Khatun says. “And during the pregnancy I felt a lot of pain in my stomach and decided to get menstrual regulation.”

Bijli Khatun’s husband had heard about menstrual regulation services at the local health centre. Bijli decided she would undergo the procedure, but soon realized she would face some issues.

“The area surrounding my house was submerged in water,” she explains. “With great difficulty I went to the centre and it was closed that day so I had to come back and once the water receded then I went to the centre again and got a menstrual regulation procedure done.”

Even with legal validity, social stigma is another factor women have to consider. “Women who come are hesitant and do not share their health problem easily,” says nurse Lovely Yasmin. “They expect complete confidentiality… as people are religious and [the woman] might have problems at home or in her locality.”

The programme also provides vital post-procedure care –most commonly pain relief- of which many women who undergo menstrual regulation, would be unable to afford themselves. Shana Khatun, 34 says “After the menstrual regulation services the hospital gave me a number of medicines I could take, I was also prescribed a few medicines which I could not buy due to [my] poor financial condition.”

Shubhutara is another client. She’s 32 and a mother of four, and decided to undergo menstrual regulation services after finding out she was pregnant again.

“Even though I have [undergone] menstrual regulation I would not want to tell others,” she says. “They will feel I have sinned and they will insult me.”

Several of the women feared being identified by the community, saying they would face a backlash due to conservative religious beliefs held in the region.

Shana Khatun says she found the hospital trustworthy and helpful. “I will be very cautious that I should not get pregnant again,” she says. “However in the event I get pregnant again, then I will come to this hospital only.”

IPPF’s Innovation Programme supports small scale initiatives, which test new ways to tackle the biggest challenges in sexual and reproductive health and rights. Each project is partnered with a research organization, in this case the University of Leicester, to ensure their impact is measured and learning shared to improve the efficacy and evidence-base of our programming.

when

country

Bangladesh

Subject

Emergencies

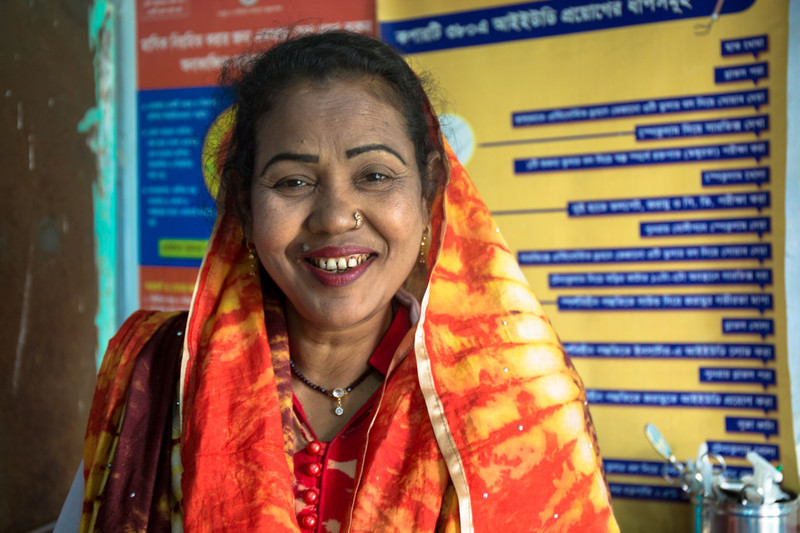

![Poly, 32, explains how six months ago her period stopped. Assuming she was pregnant she showed no other symptoms or physical changes. “My husband, father, and mother-in-law thought that my pregnancy had been eaten by a bad spirit,” Khatun says. “But when I came to the hospital the [doctor] found that I was only 3 weeks pregnant.” Concerned about health complications she decided to undergo menstrual regulation.](/sites/default/files/slideshows/Bangladesh_60475_IPPF_Victoria%20Milko_Bangladesh_IPPF%20%20.jpg)