Spotlight

A selection of stories from across the Federation

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in the face of growing opposition and the rise of the far right? These victories for sexual and reproductive rights and health are the result of relentless grassroots work and advocacy by our Member Associations, in partnership with community organizations, allied politicians, and the mobilization of public opinion.

Most Popular This Week

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in t

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan's Rising HIV Crisis: A Call for Action

On World AIDS Day, we commemorate the remarkable achievements of IPPF Member Associations in their unwavering commitment to combating the HIV epidemic.

Ensuring SRHR in Humanitarian Crises: What You Need to Know

Over the past two decades, global forced displacement has consistently increased, affecting an estimated 114 million people as of mid-2023.

Estonia, Nepal, Namibia, Japan, Thailand

The Rainbow Wave for Marriage Equality

Love wins! The fight for marriage equality has seen incredible progress worldwide, with a recent surge in legalizations.

France, Germany, Poland, United Kingdom, United States, Colombia, India, Tunisia

Abortion Rights: Latest Decisions and Developments around the World

Over the past 30 years, more than

Palestine

In their own words: The people providing sexual and reproductive health care under bombardment in Gaza

Week after week, heavy Israeli bombardment from air, land, and sea, has continued across most of the Gaza Strip.

Vanuatu

When getting to the hospital is difficult, Vanuatu mobile outreach can save lives

In the mountains of Kumera on Tanna Island, Vanuatu, the village women of Kamahaul normally spend over 10,000 Vatu ($83 USD) to travel to the nearest hospital.

Filter our stories by:

| 08 January 2021

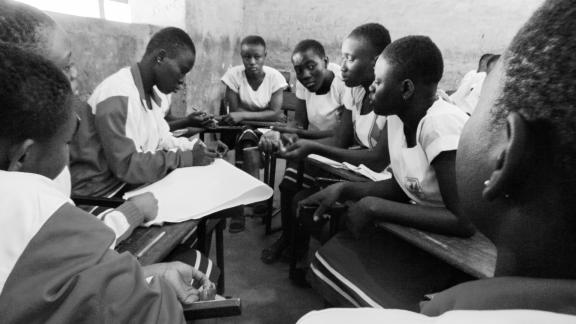

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 15 May 2025

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 25 July 2017

Female volunteers take the lead to deliver life critical health advice after the earthquake

“After the earthquake, there were so many problems. So many homes were destroyed. People are still living in temporary homes because they’re unable to rebuild their homes.” Pasang Tamang lives in Gatlang, high up in the mountains of northern Nepal, 15 kilometres from the Tibetan border. It is a sublimely beautiful village of traditional three-storied houses and Buddhist shrines resting on the slopes of a mountain and thronged by lush potato fields. The 2000 or so people living here are ethnic Tamang, a people of strong cultural traditions, who live across across Nepal but particularly in the lands bordering Tibet. The earthquake of 25 April had a devastating impact on Gatlang. Most of the traditional houses in the heart of the village were damaged or destroyed, and people were forced to move into small shacks of corrugated iron and plastic, where many still live. “Seven people died and three were injured and then later died,” says Pasang. These numbers might seems small compared to some casualty numbers in Nepal, but in a tightknit village like Gatlang, the impact was felt keenly. Hundreds of people were forced into tents. “People suffered badly from the cold,” Pasang says. “Some people caught pneumonia.” At 2240 metres above sea level, nighttime temperatures in Gatlang can plunge. Pregnant women fared particularly badly: “They were unable to access nutritious food or find a warm place. They really suffered.” Pasang herself was badly injured. “During the earthquake, I was asleep in the house because I was ill,” she says. “When I felt the earthquake, I ran out of the house and while I was running I got injured, and my mouth was damaged.” Help was at hand . “After the earthquake, there were so many organisations that came to help, including FPAN,” Pasang says. As well as setting up health camps and providing a range of health care, “they provided family planning devices to people who were in need.” Hundreds of families still live in the corrugated iron and plastic sheds that were erected as a replacement for tents. The government has been slow to distribute funds, and the villagers say that any money they have received falls far short of the cost of rebuilding their old stone homes. Pasang’s house stands empty. “We will not be able to return home because the house is cracked and if there was another earthquake, it would be completely destroyed,” she says. Since the earthquake, she has begun working as a volunteer for FPAN. Her role involves travelling around villages in the area, raising awareness about different contraceptive methods and family planning. Volunteers like Pasang perform a crucial function in a region where literacy levels and a strongly patriarchal culture mean that women marry young and have to get consent from their husbands before using contraception. In this remote community, direct contact with a volunteer who can offer advice and guidance orally, and talk to women about their broader health needs, is absolutely vital.

| 15 May 2025

Female volunteers take the lead to deliver life critical health advice after the earthquake

“After the earthquake, there were so many problems. So many homes were destroyed. People are still living in temporary homes because they’re unable to rebuild their homes.” Pasang Tamang lives in Gatlang, high up in the mountains of northern Nepal, 15 kilometres from the Tibetan border. It is a sublimely beautiful village of traditional three-storied houses and Buddhist shrines resting on the slopes of a mountain and thronged by lush potato fields. The 2000 or so people living here are ethnic Tamang, a people of strong cultural traditions, who live across across Nepal but particularly in the lands bordering Tibet. The earthquake of 25 April had a devastating impact on Gatlang. Most of the traditional houses in the heart of the village were damaged or destroyed, and people were forced to move into small shacks of corrugated iron and plastic, where many still live. “Seven people died and three were injured and then later died,” says Pasang. These numbers might seems small compared to some casualty numbers in Nepal, but in a tightknit village like Gatlang, the impact was felt keenly. Hundreds of people were forced into tents. “People suffered badly from the cold,” Pasang says. “Some people caught pneumonia.” At 2240 metres above sea level, nighttime temperatures in Gatlang can plunge. Pregnant women fared particularly badly: “They were unable to access nutritious food or find a warm place. They really suffered.” Pasang herself was badly injured. “During the earthquake, I was asleep in the house because I was ill,” she says. “When I felt the earthquake, I ran out of the house and while I was running I got injured, and my mouth was damaged.” Help was at hand . “After the earthquake, there were so many organisations that came to help, including FPAN,” Pasang says. As well as setting up health camps and providing a range of health care, “they provided family planning devices to people who were in need.” Hundreds of families still live in the corrugated iron and plastic sheds that were erected as a replacement for tents. The government has been slow to distribute funds, and the villagers say that any money they have received falls far short of the cost of rebuilding their old stone homes. Pasang’s house stands empty. “We will not be able to return home because the house is cracked and if there was another earthquake, it would be completely destroyed,” she says. Since the earthquake, she has begun working as a volunteer for FPAN. Her role involves travelling around villages in the area, raising awareness about different contraceptive methods and family planning. Volunteers like Pasang perform a crucial function in a region where literacy levels and a strongly patriarchal culture mean that women marry young and have to get consent from their husbands before using contraception. In this remote community, direct contact with a volunteer who can offer advice and guidance orally, and talk to women about their broader health needs, is absolutely vital.

| 25 July 2017

Thousands of young volunteers join us after the earthquake

The April 2015 earthquake in Nepal brought death and devastation to thousands of people – from which many are still recovering. But there was one positive outcome: after the earthquake, thousands of young people came forward to support those affected as volunteers. For Rita Tukanbanjar, a twenty-two-year-old nurse from Bhaktapur in the Kathmandu Valley, the earthquake was an eye-opening ordeal: it gave her first-hand experience of the different ways that natural disasters can affect people, particularly women and girls. “After the earthquake, FPAN was organising menstrual hygiene classes for affected people, and I took part in these,” she says. The earthquake severely affected people’s access to healthcare, but women and girls were particularly vulnerable: living in tents can make menstrual hygiene difficult, and most aid agencies tend to neglect these needs and forget to factor them into relief efforts. “After the earthquake, lots of people were living in tents, as most of the houses had collapsed,” Rita says. “During that time, the girls, especially, were facing a lot of problems maintaining their menstrual hygiene. All the shops and services for menstrual hygiene were closed.” This makes FPAN’s work even more vital. The organisation stepped into the breach and organised classes on menstrual hygiene and taught women and girls how to make sanitary pads from scratch. This was not only useful during the earthquake, but provided valuable knowledge for women and girls to use in normal life too, Rita says: “From that time on wards, women are still making their own sanitary pads.” In an impoverished country like Nepal, many women and girls can simply not afford to buy sanitary pads and tampons. Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world with gross domestic product per capita of just $691 in 2014. In this largely patriarchal culture, the needs of women often come low down in a family’s priorities. “This is very important work and very useful,” Rita says. The women and girls also learned about how to protect themselves from sexual violence, which saw a surge in the weeks after the earthquake, with men preying on people living in tents and temporary shacks. Rita and her family lived in a tent for 20 days. “There was always the fear of getting abused,” she says. Eventually they managed to return home to live in the ruins of their house: “one part was undamaged so we covered it with a tent and managed to sleep there, on the ground floor.” Seeing the suffering the earthquake had caused, and the work FPAN and other organisations were doing to alleviate it, cemented Rita’s decision to begin volunteering. “After the earthquake, when things got back to normal, I joined FPAN.” She also completed her nursing degree, which had been interrupted by the disaster. “Since joining FPAN, I have been very busy creating awareness about sexual rights and all kinds of things, and running Friday sexual education classes in schools,” Rita says. “And since I have a nursing background, people often come to me with problems, and I give them suggestions and share my knowledge with them.” She also hopes to become a staff nurse for FPAN. “If that opportunity comes my way, then I would definitely love to do it,” she says.

| 15 May 2025

Thousands of young volunteers join us after the earthquake

The April 2015 earthquake in Nepal brought death and devastation to thousands of people – from which many are still recovering. But there was one positive outcome: after the earthquake, thousands of young people came forward to support those affected as volunteers. For Rita Tukanbanjar, a twenty-two-year-old nurse from Bhaktapur in the Kathmandu Valley, the earthquake was an eye-opening ordeal: it gave her first-hand experience of the different ways that natural disasters can affect people, particularly women and girls. “After the earthquake, FPAN was organising menstrual hygiene classes for affected people, and I took part in these,” she says. The earthquake severely affected people’s access to healthcare, but women and girls were particularly vulnerable: living in tents can make menstrual hygiene difficult, and most aid agencies tend to neglect these needs and forget to factor them into relief efforts. “After the earthquake, lots of people were living in tents, as most of the houses had collapsed,” Rita says. “During that time, the girls, especially, were facing a lot of problems maintaining their menstrual hygiene. All the shops and services for menstrual hygiene were closed.” This makes FPAN’s work even more vital. The organisation stepped into the breach and organised classes on menstrual hygiene and taught women and girls how to make sanitary pads from scratch. This was not only useful during the earthquake, but provided valuable knowledge for women and girls to use in normal life too, Rita says: “From that time on wards, women are still making their own sanitary pads.” In an impoverished country like Nepal, many women and girls can simply not afford to buy sanitary pads and tampons. Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world with gross domestic product per capita of just $691 in 2014. In this largely patriarchal culture, the needs of women often come low down in a family’s priorities. “This is very important work and very useful,” Rita says. The women and girls also learned about how to protect themselves from sexual violence, which saw a surge in the weeks after the earthquake, with men preying on people living in tents and temporary shacks. Rita and her family lived in a tent for 20 days. “There was always the fear of getting abused,” she says. Eventually they managed to return home to live in the ruins of their house: “one part was undamaged so we covered it with a tent and managed to sleep there, on the ground floor.” Seeing the suffering the earthquake had caused, and the work FPAN and other organisations were doing to alleviate it, cemented Rita’s decision to begin volunteering. “After the earthquake, when things got back to normal, I joined FPAN.” She also completed her nursing degree, which had been interrupted by the disaster. “Since joining FPAN, I have been very busy creating awareness about sexual rights and all kinds of things, and running Friday sexual education classes in schools,” Rita says. “And since I have a nursing background, people often come to me with problems, and I give them suggestions and share my knowledge with them.” She also hopes to become a staff nurse for FPAN. “If that opportunity comes my way, then I would definitely love to do it,” she says.

| 08 January 2021

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 15 May 2025

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 25 July 2017

Female volunteers take the lead to deliver life critical health advice after the earthquake

“After the earthquake, there were so many problems. So many homes were destroyed. People are still living in temporary homes because they’re unable to rebuild their homes.” Pasang Tamang lives in Gatlang, high up in the mountains of northern Nepal, 15 kilometres from the Tibetan border. It is a sublimely beautiful village of traditional three-storied houses and Buddhist shrines resting on the slopes of a mountain and thronged by lush potato fields. The 2000 or so people living here are ethnic Tamang, a people of strong cultural traditions, who live across across Nepal but particularly in the lands bordering Tibet. The earthquake of 25 April had a devastating impact on Gatlang. Most of the traditional houses in the heart of the village were damaged or destroyed, and people were forced to move into small shacks of corrugated iron and plastic, where many still live. “Seven people died and three were injured and then later died,” says Pasang. These numbers might seems small compared to some casualty numbers in Nepal, but in a tightknit village like Gatlang, the impact was felt keenly. Hundreds of people were forced into tents. “People suffered badly from the cold,” Pasang says. “Some people caught pneumonia.” At 2240 metres above sea level, nighttime temperatures in Gatlang can plunge. Pregnant women fared particularly badly: “They were unable to access nutritious food or find a warm place. They really suffered.” Pasang herself was badly injured. “During the earthquake, I was asleep in the house because I was ill,” she says. “When I felt the earthquake, I ran out of the house and while I was running I got injured, and my mouth was damaged.” Help was at hand . “After the earthquake, there were so many organisations that came to help, including FPAN,” Pasang says. As well as setting up health camps and providing a range of health care, “they provided family planning devices to people who were in need.” Hundreds of families still live in the corrugated iron and plastic sheds that were erected as a replacement for tents. The government has been slow to distribute funds, and the villagers say that any money they have received falls far short of the cost of rebuilding their old stone homes. Pasang’s house stands empty. “We will not be able to return home because the house is cracked and if there was another earthquake, it would be completely destroyed,” she says. Since the earthquake, she has begun working as a volunteer for FPAN. Her role involves travelling around villages in the area, raising awareness about different contraceptive methods and family planning. Volunteers like Pasang perform a crucial function in a region where literacy levels and a strongly patriarchal culture mean that women marry young and have to get consent from their husbands before using contraception. In this remote community, direct contact with a volunteer who can offer advice and guidance orally, and talk to women about their broader health needs, is absolutely vital.

| 15 May 2025

Female volunteers take the lead to deliver life critical health advice after the earthquake

“After the earthquake, there were so many problems. So many homes were destroyed. People are still living in temporary homes because they’re unable to rebuild their homes.” Pasang Tamang lives in Gatlang, high up in the mountains of northern Nepal, 15 kilometres from the Tibetan border. It is a sublimely beautiful village of traditional three-storied houses and Buddhist shrines resting on the slopes of a mountain and thronged by lush potato fields. The 2000 or so people living here are ethnic Tamang, a people of strong cultural traditions, who live across across Nepal but particularly in the lands bordering Tibet. The earthquake of 25 April had a devastating impact on Gatlang. Most of the traditional houses in the heart of the village were damaged or destroyed, and people were forced to move into small shacks of corrugated iron and plastic, where many still live. “Seven people died and three were injured and then later died,” says Pasang. These numbers might seems small compared to some casualty numbers in Nepal, but in a tightknit village like Gatlang, the impact was felt keenly. Hundreds of people were forced into tents. “People suffered badly from the cold,” Pasang says. “Some people caught pneumonia.” At 2240 metres above sea level, nighttime temperatures in Gatlang can plunge. Pregnant women fared particularly badly: “They were unable to access nutritious food or find a warm place. They really suffered.” Pasang herself was badly injured. “During the earthquake, I was asleep in the house because I was ill,” she says. “When I felt the earthquake, I ran out of the house and while I was running I got injured, and my mouth was damaged.” Help was at hand . “After the earthquake, there were so many organisations that came to help, including FPAN,” Pasang says. As well as setting up health camps and providing a range of health care, “they provided family planning devices to people who were in need.” Hundreds of families still live in the corrugated iron and plastic sheds that were erected as a replacement for tents. The government has been slow to distribute funds, and the villagers say that any money they have received falls far short of the cost of rebuilding their old stone homes. Pasang’s house stands empty. “We will not be able to return home because the house is cracked and if there was another earthquake, it would be completely destroyed,” she says. Since the earthquake, she has begun working as a volunteer for FPAN. Her role involves travelling around villages in the area, raising awareness about different contraceptive methods and family planning. Volunteers like Pasang perform a crucial function in a region where literacy levels and a strongly patriarchal culture mean that women marry young and have to get consent from their husbands before using contraception. In this remote community, direct contact with a volunteer who can offer advice and guidance orally, and talk to women about their broader health needs, is absolutely vital.

| 25 July 2017

Thousands of young volunteers join us after the earthquake

The April 2015 earthquake in Nepal brought death and devastation to thousands of people – from which many are still recovering. But there was one positive outcome: after the earthquake, thousands of young people came forward to support those affected as volunteers. For Rita Tukanbanjar, a twenty-two-year-old nurse from Bhaktapur in the Kathmandu Valley, the earthquake was an eye-opening ordeal: it gave her first-hand experience of the different ways that natural disasters can affect people, particularly women and girls. “After the earthquake, FPAN was organising menstrual hygiene classes for affected people, and I took part in these,” she says. The earthquake severely affected people’s access to healthcare, but women and girls were particularly vulnerable: living in tents can make menstrual hygiene difficult, and most aid agencies tend to neglect these needs and forget to factor them into relief efforts. “After the earthquake, lots of people were living in tents, as most of the houses had collapsed,” Rita says. “During that time, the girls, especially, were facing a lot of problems maintaining their menstrual hygiene. All the shops and services for menstrual hygiene were closed.” This makes FPAN’s work even more vital. The organisation stepped into the breach and organised classes on menstrual hygiene and taught women and girls how to make sanitary pads from scratch. This was not only useful during the earthquake, but provided valuable knowledge for women and girls to use in normal life too, Rita says: “From that time on wards, women are still making their own sanitary pads.” In an impoverished country like Nepal, many women and girls can simply not afford to buy sanitary pads and tampons. Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world with gross domestic product per capita of just $691 in 2014. In this largely patriarchal culture, the needs of women often come low down in a family’s priorities. “This is very important work and very useful,” Rita says. The women and girls also learned about how to protect themselves from sexual violence, which saw a surge in the weeks after the earthquake, with men preying on people living in tents and temporary shacks. Rita and her family lived in a tent for 20 days. “There was always the fear of getting abused,” she says. Eventually they managed to return home to live in the ruins of their house: “one part was undamaged so we covered it with a tent and managed to sleep there, on the ground floor.” Seeing the suffering the earthquake had caused, and the work FPAN and other organisations were doing to alleviate it, cemented Rita’s decision to begin volunteering. “After the earthquake, when things got back to normal, I joined FPAN.” She also completed her nursing degree, which had been interrupted by the disaster. “Since joining FPAN, I have been very busy creating awareness about sexual rights and all kinds of things, and running Friday sexual education classes in schools,” Rita says. “And since I have a nursing background, people often come to me with problems, and I give them suggestions and share my knowledge with them.” She also hopes to become a staff nurse for FPAN. “If that opportunity comes my way, then I would definitely love to do it,” she says.

| 15 May 2025

Thousands of young volunteers join us after the earthquake

The April 2015 earthquake in Nepal brought death and devastation to thousands of people – from which many are still recovering. But there was one positive outcome: after the earthquake, thousands of young people came forward to support those affected as volunteers. For Rita Tukanbanjar, a twenty-two-year-old nurse from Bhaktapur in the Kathmandu Valley, the earthquake was an eye-opening ordeal: it gave her first-hand experience of the different ways that natural disasters can affect people, particularly women and girls. “After the earthquake, FPAN was organising menstrual hygiene classes for affected people, and I took part in these,” she says. The earthquake severely affected people’s access to healthcare, but women and girls were particularly vulnerable: living in tents can make menstrual hygiene difficult, and most aid agencies tend to neglect these needs and forget to factor them into relief efforts. “After the earthquake, lots of people were living in tents, as most of the houses had collapsed,” Rita says. “During that time, the girls, especially, were facing a lot of problems maintaining their menstrual hygiene. All the shops and services for menstrual hygiene were closed.” This makes FPAN’s work even more vital. The organisation stepped into the breach and organised classes on menstrual hygiene and taught women and girls how to make sanitary pads from scratch. This was not only useful during the earthquake, but provided valuable knowledge for women and girls to use in normal life too, Rita says: “From that time on wards, women are still making their own sanitary pads.” In an impoverished country like Nepal, many women and girls can simply not afford to buy sanitary pads and tampons. Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world with gross domestic product per capita of just $691 in 2014. In this largely patriarchal culture, the needs of women often come low down in a family’s priorities. “This is very important work and very useful,” Rita says. The women and girls also learned about how to protect themselves from sexual violence, which saw a surge in the weeks after the earthquake, with men preying on people living in tents and temporary shacks. Rita and her family lived in a tent for 20 days. “There was always the fear of getting abused,” she says. Eventually they managed to return home to live in the ruins of their house: “one part was undamaged so we covered it with a tent and managed to sleep there, on the ground floor.” Seeing the suffering the earthquake had caused, and the work FPAN and other organisations were doing to alleviate it, cemented Rita’s decision to begin volunteering. “After the earthquake, when things got back to normal, I joined FPAN.” She also completed her nursing degree, which had been interrupted by the disaster. “Since joining FPAN, I have been very busy creating awareness about sexual rights and all kinds of things, and running Friday sexual education classes in schools,” Rita says. “And since I have a nursing background, people often come to me with problems, and I give them suggestions and share my knowledge with them.” She also hopes to become a staff nurse for FPAN. “If that opportunity comes my way, then I would definitely love to do it,” she says.