Spotlight

A selection of stories from across the Federation

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in the face of growing opposition and the rise of the far right? These victories for sexual and reproductive rights and health are the result of relentless grassroots work and advocacy by our Member Associations, in partnership with community organizations, allied politicians, and the mobilization of public opinion.

Most Popular This Week

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in t

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan's Rising HIV Crisis: A Call for Action

On World AIDS Day, we commemorate the remarkable achievements of IPPF Member Associations in their unwavering commitment to combating the HIV epidemic.

Ensuring SRHR in Humanitarian Crises: What You Need to Know

Over the past two decades, global forced displacement has consistently increased, affecting an estimated 114 million people as of mid-2023.

Estonia, Nepal, Namibia, Japan, Thailand

The Rainbow Wave for Marriage Equality

Love wins! The fight for marriage equality has seen incredible progress worldwide, with a recent surge in legalizations.

France, Germany, Poland, United Kingdom, United States, Colombia, India, Tunisia

Abortion Rights: Latest Decisions and Developments around the World

Over the past 30 years, more than

Palestine

In their own words: The people providing sexual and reproductive health care under bombardment in Gaza

Week after week, heavy Israeli bombardment from air, land, and sea, has continued across most of the Gaza Strip.

Vanuatu

When getting to the hospital is difficult, Vanuatu mobile outreach can save lives

In the mountains of Kumera on Tanna Island, Vanuatu, the village women of Kamahaul normally spend over 10,000 Vatu ($83 USD) to travel to the nearest hospital.

Filter our stories by:

- Afghan Family Guidance Association

- Albanian Center for Population and Development

- Asociación Pro-Bienestar de la Familia Colombiana

- Associação Moçambicana para Desenvolvimento da Família

- Association Béninoise pour la Promotion de la Famille

- (-) Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial

- Association Malienne pour la Protection et la Promotion de la Famille

- Association pour le Bien-Etre Familial/Naissances Désirables

- Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Étre Familial

- Association Togolaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial

- Association Tunisienne de la Santé de la Reproduction

- Botswana Family Welfare Association

- Cameroon National Association for Family Welfare

- Cook Islands Family Welfare Association

- Eesti Seksuaaltervise Liit / Estonian Sexual Health Association

- Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia

- Family Planning Association of India

- Family Planning Association of Malawi

- Family Planning Association of Nepal

- Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka

- Family Planning Association of Trinidad and Tobago

- Foundation for the Promotion of Responsible Parenthood - Aruba

- Indonesian Planned Parenthood Association

- Jamaica Family Planning Association

- Kazakhstan Association on Sexual and Reproductive Health (KMPA)

- Kiribati Family Health Association

- Lesotho Planned Parenthood Association

- Mouvement Français pour le Planning Familial

- Palestinian Family Planning and Protection Association (PFPPA)

- Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana

- Planned Parenthood Association of Thailand

- Planned Parenthood Association of Zambia

- Planned Parenthood Federation of America

- Planned Parenthood Federation of Nigeria

- Pro Familia - Germany

- Rahnuma-Family Planning Association of Pakistan

- Reproductive & Family Health Association of Fiji

- Reproductive Health Association of Cambodia (RHAC)

- Reproductive Health Uganda

- Somaliland Family Health Association

- Sudan Family Planning Association

- (-) Tonga Family Health Association

- Vanuatu Family Health Association

| 29 March 2018

"I have a feeling the future will be better"

Leiti is a Tongan word to describe transgender women, it comes from the English word “lady”. In Tonga the transgender community is organized by the Tonga Leiti Association (TLA), and with the support of Tonga Family Health Association (TFHA). Together they are educating people to help stop the discrimination and stigma surrounding the Leiti community. Leilani, who identifies as a leiti, has been working with the Tonga Leiti Association, supported by Tonga Health Family Association to battle the stigma surrounding the leiti and LGBTI+ community in Tonga. She says "I started to dress like a leiti at a very young age. Being a leiti in a Tongan family is very difficult because being a leiti or having a son who’s a leiti are considered shameful, so for the family (it) is very difficult to accept us. Many leitis run away from their families." Frequently facing abuse Access to health care and sexual and reproductive health service is another difficulty the leiti community face: going to public clinics, they often face abuse and are more likely to be ignored or dismissed by staff. When they are turned away from other clinics, Leilani knows she can always rely on Tonga Health Family Association for help. 'I think Tonga Family Health has done a lot up to now. They always come and do our annual HIV testing and they supply us (with) some condom because we do the condom distribution here in Tonga and if we have a case in our members or anybody come to our office we refer them to Tonga Family Health. They really, really help us a lot. They (are the) only one that can understand us." Tonga Family Health Association and Tonga Leiti Association partnership allows for both organisations to attend training workshops run by one another. A valuable opportunity not only for clinic staff but for volunteers like Leilani. "When the Tonga Family Health run the training they always ask some members from TLA to come and train with them and we do the same with them. When I give a presentation at the TFHA's clinic, I share with people what we do; I ask them for to change their mindset and how they look about us." Overcoming stigma and discrimination With her training, Leilani visits schools to help educate, inform and overcome the stigma and discrimination surrounding the leiti community. Many young leiti's drop out of school at an early age due to verbal, physical and in some cases sexual abuse. Slowly, Leilani is seeing a positive change in the schools she visits. “We go to school because there a lot of discrimination of the leiti's in high school and primary school too. I have been going from school to school for two years. My plan to visit all the schools in Tonga. We mostly go to all-boys schools is because discrimination in school is mostly done by boys. I was very happy last year when I went to a boys school and so how they really appreciate the work and how well they treated the Leiti's in the school." In February, Tonga was hit by tropical cyclone Gita, the worst cyclone to hit the island in over 60 years. Leilani worries that not enough is being done to ensure the needs of the Leiti and LGBTI+ community is being met during and post humanitarian disasters. "We are one of the vulnerable groups, after the cyclone Gita we should be one of the first priority for the government, or the hospital or any donations. Cause our life is very unique and we are easy to harm." Despite the hardships surrounding the leiti community, Leilani is hopeful for the future, "I can see a lot of families that now accept leiti's in their house and they treat them well. I have a feeling the future will be better. Please stop discriminating against us, but love us. We are here to stay, we are not here to chase away." Watch the Humanitarian teams response to Cyclone Gita

| 15 May 2025

"I have a feeling the future will be better"

Leiti is a Tongan word to describe transgender women, it comes from the English word “lady”. In Tonga the transgender community is organized by the Tonga Leiti Association (TLA), and with the support of Tonga Family Health Association (TFHA). Together they are educating people to help stop the discrimination and stigma surrounding the Leiti community. Leilani, who identifies as a leiti, has been working with the Tonga Leiti Association, supported by Tonga Health Family Association to battle the stigma surrounding the leiti and LGBTI+ community in Tonga. She says "I started to dress like a leiti at a very young age. Being a leiti in a Tongan family is very difficult because being a leiti or having a son who’s a leiti are considered shameful, so for the family (it) is very difficult to accept us. Many leitis run away from their families." Frequently facing abuse Access to health care and sexual and reproductive health service is another difficulty the leiti community face: going to public clinics, they often face abuse and are more likely to be ignored or dismissed by staff. When they are turned away from other clinics, Leilani knows she can always rely on Tonga Health Family Association for help. 'I think Tonga Family Health has done a lot up to now. They always come and do our annual HIV testing and they supply us (with) some condom because we do the condom distribution here in Tonga and if we have a case in our members or anybody come to our office we refer them to Tonga Family Health. They really, really help us a lot. They (are the) only one that can understand us." Tonga Family Health Association and Tonga Leiti Association partnership allows for both organisations to attend training workshops run by one another. A valuable opportunity not only for clinic staff but for volunteers like Leilani. "When the Tonga Family Health run the training they always ask some members from TLA to come and train with them and we do the same with them. When I give a presentation at the TFHA's clinic, I share with people what we do; I ask them for to change their mindset and how they look about us." Overcoming stigma and discrimination With her training, Leilani visits schools to help educate, inform and overcome the stigma and discrimination surrounding the leiti community. Many young leiti's drop out of school at an early age due to verbal, physical and in some cases sexual abuse. Slowly, Leilani is seeing a positive change in the schools she visits. “We go to school because there a lot of discrimination of the leiti's in high school and primary school too. I have been going from school to school for two years. My plan to visit all the schools in Tonga. We mostly go to all-boys schools is because discrimination in school is mostly done by boys. I was very happy last year when I went to a boys school and so how they really appreciate the work and how well they treated the Leiti's in the school." In February, Tonga was hit by tropical cyclone Gita, the worst cyclone to hit the island in over 60 years. Leilani worries that not enough is being done to ensure the needs of the Leiti and LGBTI+ community is being met during and post humanitarian disasters. "We are one of the vulnerable groups, after the cyclone Gita we should be one of the first priority for the government, or the hospital or any donations. Cause our life is very unique and we are easy to harm." Despite the hardships surrounding the leiti community, Leilani is hopeful for the future, "I can see a lot of families that now accept leiti's in their house and they treat them well. I have a feeling the future will be better. Please stop discriminating against us, but love us. We are here to stay, we are not here to chase away." Watch the Humanitarian teams response to Cyclone Gita

| 22 January 2018

"I am a living example of having a good life..."

At a local bar, we meet nine women from Kirundo. They’re all sex workers who became friends through Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial's (ABUBEF) peer educator project. Yvonne is 40 and has known that she’s HIV-positive for 22 years. After her diagnosis she was isolated from her friends and stigmatized both in public and at home, where she was even given separate plates to eat from. “I started to get drunk every day,” she says. “I hoped death would take me in my sleep. I didn’t believe in tomorrow. I was lost and lonely. Until I got to the ABUBEF clinic.” ABUBEF has supported her treatment for the past six years. “I take my pill every day and I am living example of having a good life even with a previous death sentence,” Yvonne explains. “But I see that the awareness of HIV, protection and testing provided by ABUBEF is still very small.” Yvonne became a peer educator, speaking in public about HIV awareness, wearing an ABUBEF T-shirt. The project spread to the wider region, and volunteers were given travel expenses, materials and training, along with condoms for distribution. But funding cuts mean those expenses are no longer available. Yvonne says she’ll carry on in Kirundo even if she can’t travel more widely like she used to. Her friend, 29-year-old Perusi, shares her experience of ABUBEF as a safe space where her privacy will be respected. It often happens, she says, that her clients rape her, and run away, failing to pay. Since sex work is illegal, she says, and there’s no protection from the authorities, and sex workers like her often feel rejected by society. But at ABUBEF’s clinics, they are welcomed.

| 16 May 2025

"I am a living example of having a good life..."

At a local bar, we meet nine women from Kirundo. They’re all sex workers who became friends through Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial's (ABUBEF) peer educator project. Yvonne is 40 and has known that she’s HIV-positive for 22 years. After her diagnosis she was isolated from her friends and stigmatized both in public and at home, where she was even given separate plates to eat from. “I started to get drunk every day,” she says. “I hoped death would take me in my sleep. I didn’t believe in tomorrow. I was lost and lonely. Until I got to the ABUBEF clinic.” ABUBEF has supported her treatment for the past six years. “I take my pill every day and I am living example of having a good life even with a previous death sentence,” Yvonne explains. “But I see that the awareness of HIV, protection and testing provided by ABUBEF is still very small.” Yvonne became a peer educator, speaking in public about HIV awareness, wearing an ABUBEF T-shirt. The project spread to the wider region, and volunteers were given travel expenses, materials and training, along with condoms for distribution. But funding cuts mean those expenses are no longer available. Yvonne says she’ll carry on in Kirundo even if she can’t travel more widely like she used to. Her friend, 29-year-old Perusi, shares her experience of ABUBEF as a safe space where her privacy will be respected. It often happens, she says, that her clients rape her, and run away, failing to pay. Since sex work is illegal, she says, and there’s no protection from the authorities, and sex workers like her often feel rejected by society. But at ABUBEF’s clinics, they are welcomed.

| 22 January 2018

“They saved the life of me and my child”

Monica has never told anyone about the attack. She was pregnant at the time, already had two teenage sons, and rape is a taboo subject in her community in Burundi. Knowing that her attacker was HIV-positive, and fearing that her husband would accuse her of provocation - or worse still, leave her - she turned to a place she knew would help. ABUBEF is the Association Burundaise Pour Le Bien-Etre Familial. Their clinic in Kirundo offered Monica HIV counselling and treatment for the duration of her pregnancy. Above all, ABUBEF offered privacy. Neither Monica nor her daughter has tested positive for HIV. “They saved the life of me and my child,” Monica says. “I hope they get an award for their psychological and health support for women.” Three years on from the attack, Monica, now 45, raises her children and tends the family farm where she grows beans, cassava, potatoes and rice. She’s proud of her eldest son who’s due to start university this year. She educates her boys against violence, and spreads the word about ABUBEF. Monica speaks to other women to make sure they know where to seek help if they need it. Her attacker still lives in the neighbourhood, and she worries that he’s transmitting HIV. But the ABUBEF clinic that helped Monica is under threat from funding cuts. The possibility that it could close prompted her to tell her story. “This is a disaster for our community,” she says. “I know how much the clinic needs support from donors, how much they need new equipment and money for new staff. I want people to know that this facility is one of a kind - and without it many people will be lost.”

| 16 May 2025

“They saved the life of me and my child”

Monica has never told anyone about the attack. She was pregnant at the time, already had two teenage sons, and rape is a taboo subject in her community in Burundi. Knowing that her attacker was HIV-positive, and fearing that her husband would accuse her of provocation - or worse still, leave her - she turned to a place she knew would help. ABUBEF is the Association Burundaise Pour Le Bien-Etre Familial. Their clinic in Kirundo offered Monica HIV counselling and treatment for the duration of her pregnancy. Above all, ABUBEF offered privacy. Neither Monica nor her daughter has tested positive for HIV. “They saved the life of me and my child,” Monica says. “I hope they get an award for their psychological and health support for women.” Three years on from the attack, Monica, now 45, raises her children and tends the family farm where she grows beans, cassava, potatoes and rice. She’s proud of her eldest son who’s due to start university this year. She educates her boys against violence, and spreads the word about ABUBEF. Monica speaks to other women to make sure they know where to seek help if they need it. Her attacker still lives in the neighbourhood, and she worries that he’s transmitting HIV. But the ABUBEF clinic that helped Monica is under threat from funding cuts. The possibility that it could close prompted her to tell her story. “This is a disaster for our community,” she says. “I know how much the clinic needs support from donors, how much they need new equipment and money for new staff. I want people to know that this facility is one of a kind - and without it many people will be lost.”

| 19 January 2018

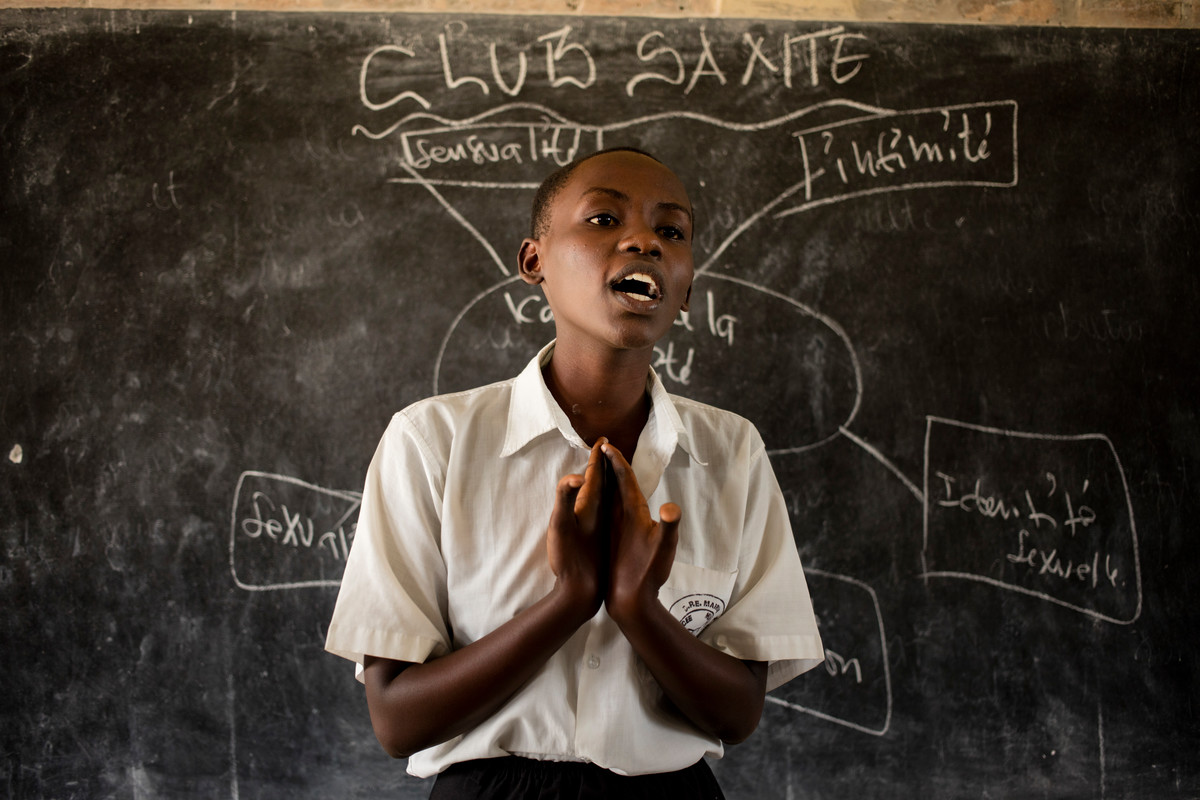

“I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one"

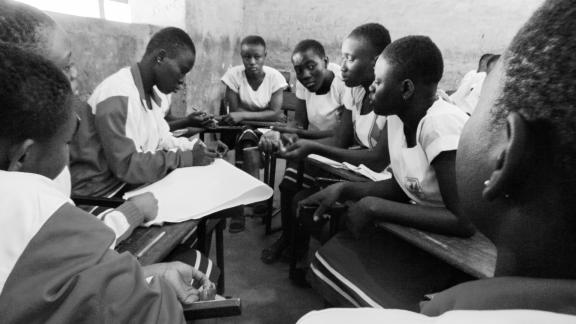

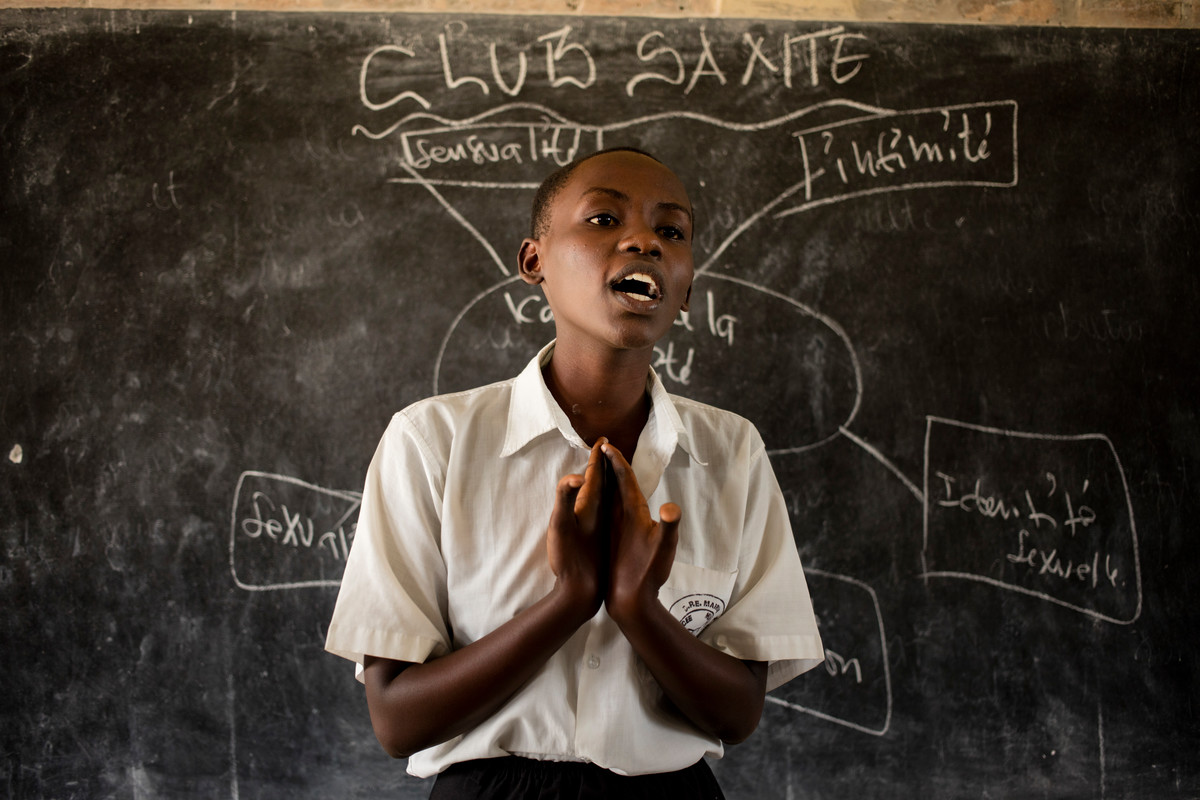

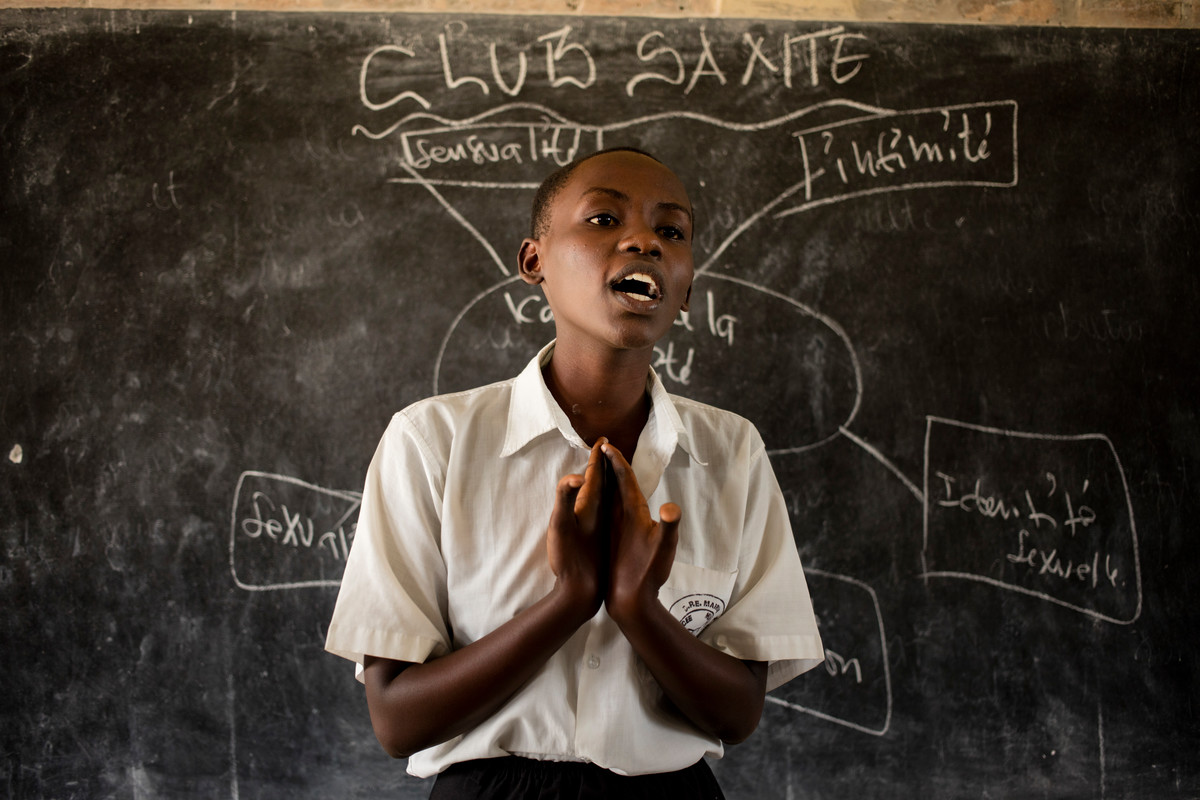

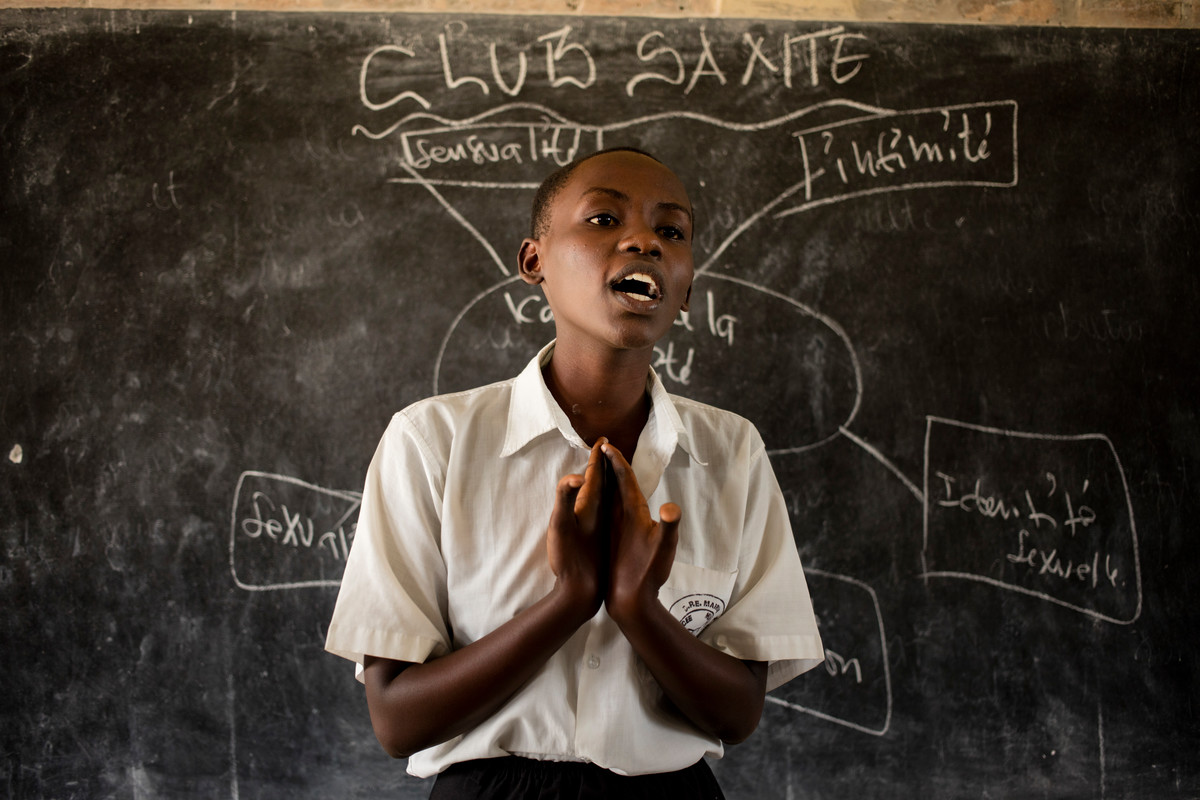

On Friday afternoon in Municipal Lycee of Nyakabiga, Burundi, headmistress Chantal Keza is introducing her students to the medical staff from Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ABUBEF). Peer educators at the school, trained by ABUBEF, will perform a short drama based around sexual health and will answer questions about contraception methods from students. One of the actresses is peer educator Ammande Berlyne Dushime. Ammande, who is 17 years old is one of three peer educators at the school. Ammande, together with her friends, perform their short drama on the stage based on a young girls quest for information on contraception. It ends on a positive note, with the girl receiving useful and correct information from a peer educator at her school. A story that could be a very real life scenario at her school. Peer programmes that trained Ammande, are under threat of closure due to the Global Gag rule. Ammande says, “I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one. I am ready to go on with work as peer educator, but if there are not going to be regular visits by the medical stuff from the clinic, then we will have no one to seek information and advice from. I am just a teenager, I know so little. Not only I will lose my support, but also I will not be taken serious by my schoolmates. With such important topic like sexual education and contraception, I am not the authority. I can only show the right way to go. And this road leads to ABUBEF.” She says “As peer educator I am responsible for Saturday morning meetings at the clinic. We sing songs, play games, have fun and learn new things about sex education, contraception, HIV protection and others. Visiting the clinic is then very easy, and no student has to be afraid, that showing up at the clinic that treats HIV positive people, will ruin their reputation. Now they know that we can meet there openly, and undercover of these meetings seek for help, information, professional advice and contraception methods” Peer educator classes are a safe and open place for students to openly talk about their sexual health. The Global Gage Rule will force peer educator programmes like this to close due to lack of funding. Help us bridge the funding gap Learn more about the Global Gag Rule

| 16 May 2025

“I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one"

On Friday afternoon in Municipal Lycee of Nyakabiga, Burundi, headmistress Chantal Keza is introducing her students to the medical staff from Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ABUBEF). Peer educators at the school, trained by ABUBEF, will perform a short drama based around sexual health and will answer questions about contraception methods from students. One of the actresses is peer educator Ammande Berlyne Dushime. Ammande, who is 17 years old is one of three peer educators at the school. Ammande, together with her friends, perform their short drama on the stage based on a young girls quest for information on contraception. It ends on a positive note, with the girl receiving useful and correct information from a peer educator at her school. A story that could be a very real life scenario at her school. Peer programmes that trained Ammande, are under threat of closure due to the Global Gag rule. Ammande says, “I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one. I am ready to go on with work as peer educator, but if there are not going to be regular visits by the medical stuff from the clinic, then we will have no one to seek information and advice from. I am just a teenager, I know so little. Not only I will lose my support, but also I will not be taken serious by my schoolmates. With such important topic like sexual education and contraception, I am not the authority. I can only show the right way to go. And this road leads to ABUBEF.” She says “As peer educator I am responsible for Saturday morning meetings at the clinic. We sing songs, play games, have fun and learn new things about sex education, contraception, HIV protection and others. Visiting the clinic is then very easy, and no student has to be afraid, that showing up at the clinic that treats HIV positive people, will ruin their reputation. Now they know that we can meet there openly, and undercover of these meetings seek for help, information, professional advice and contraception methods” Peer educator classes are a safe and open place for students to openly talk about their sexual health. The Global Gage Rule will force peer educator programmes like this to close due to lack of funding. Help us bridge the funding gap Learn more about the Global Gag Rule

| 29 March 2018

"I have a feeling the future will be better"

Leiti is a Tongan word to describe transgender women, it comes from the English word “lady”. In Tonga the transgender community is organized by the Tonga Leiti Association (TLA), and with the support of Tonga Family Health Association (TFHA). Together they are educating people to help stop the discrimination and stigma surrounding the Leiti community. Leilani, who identifies as a leiti, has been working with the Tonga Leiti Association, supported by Tonga Health Family Association to battle the stigma surrounding the leiti and LGBTI+ community in Tonga. She says "I started to dress like a leiti at a very young age. Being a leiti in a Tongan family is very difficult because being a leiti or having a son who’s a leiti are considered shameful, so for the family (it) is very difficult to accept us. Many leitis run away from their families." Frequently facing abuse Access to health care and sexual and reproductive health service is another difficulty the leiti community face: going to public clinics, they often face abuse and are more likely to be ignored or dismissed by staff. When they are turned away from other clinics, Leilani knows she can always rely on Tonga Health Family Association for help. 'I think Tonga Family Health has done a lot up to now. They always come and do our annual HIV testing and they supply us (with) some condom because we do the condom distribution here in Tonga and if we have a case in our members or anybody come to our office we refer them to Tonga Family Health. They really, really help us a lot. They (are the) only one that can understand us." Tonga Family Health Association and Tonga Leiti Association partnership allows for both organisations to attend training workshops run by one another. A valuable opportunity not only for clinic staff but for volunteers like Leilani. "When the Tonga Family Health run the training they always ask some members from TLA to come and train with them and we do the same with them. When I give a presentation at the TFHA's clinic, I share with people what we do; I ask them for to change their mindset and how they look about us." Overcoming stigma and discrimination With her training, Leilani visits schools to help educate, inform and overcome the stigma and discrimination surrounding the leiti community. Many young leiti's drop out of school at an early age due to verbal, physical and in some cases sexual abuse. Slowly, Leilani is seeing a positive change in the schools she visits. “We go to school because there a lot of discrimination of the leiti's in high school and primary school too. I have been going from school to school for two years. My plan to visit all the schools in Tonga. We mostly go to all-boys schools is because discrimination in school is mostly done by boys. I was very happy last year when I went to a boys school and so how they really appreciate the work and how well they treated the Leiti's in the school." In February, Tonga was hit by tropical cyclone Gita, the worst cyclone to hit the island in over 60 years. Leilani worries that not enough is being done to ensure the needs of the Leiti and LGBTI+ community is being met during and post humanitarian disasters. "We are one of the vulnerable groups, after the cyclone Gita we should be one of the first priority for the government, or the hospital or any donations. Cause our life is very unique and we are easy to harm." Despite the hardships surrounding the leiti community, Leilani is hopeful for the future, "I can see a lot of families that now accept leiti's in their house and they treat them well. I have a feeling the future will be better. Please stop discriminating against us, but love us. We are here to stay, we are not here to chase away." Watch the Humanitarian teams response to Cyclone Gita

| 15 May 2025

"I have a feeling the future will be better"

Leiti is a Tongan word to describe transgender women, it comes from the English word “lady”. In Tonga the transgender community is organized by the Tonga Leiti Association (TLA), and with the support of Tonga Family Health Association (TFHA). Together they are educating people to help stop the discrimination and stigma surrounding the Leiti community. Leilani, who identifies as a leiti, has been working with the Tonga Leiti Association, supported by Tonga Health Family Association to battle the stigma surrounding the leiti and LGBTI+ community in Tonga. She says "I started to dress like a leiti at a very young age. Being a leiti in a Tongan family is very difficult because being a leiti or having a son who’s a leiti are considered shameful, so for the family (it) is very difficult to accept us. Many leitis run away from their families." Frequently facing abuse Access to health care and sexual and reproductive health service is another difficulty the leiti community face: going to public clinics, they often face abuse and are more likely to be ignored or dismissed by staff. When they are turned away from other clinics, Leilani knows she can always rely on Tonga Health Family Association for help. 'I think Tonga Family Health has done a lot up to now. They always come and do our annual HIV testing and they supply us (with) some condom because we do the condom distribution here in Tonga and if we have a case in our members or anybody come to our office we refer them to Tonga Family Health. They really, really help us a lot. They (are the) only one that can understand us." Tonga Family Health Association and Tonga Leiti Association partnership allows for both organisations to attend training workshops run by one another. A valuable opportunity not only for clinic staff but for volunteers like Leilani. "When the Tonga Family Health run the training they always ask some members from TLA to come and train with them and we do the same with them. When I give a presentation at the TFHA's clinic, I share with people what we do; I ask them for to change their mindset and how they look about us." Overcoming stigma and discrimination With her training, Leilani visits schools to help educate, inform and overcome the stigma and discrimination surrounding the leiti community. Many young leiti's drop out of school at an early age due to verbal, physical and in some cases sexual abuse. Slowly, Leilani is seeing a positive change in the schools she visits. “We go to school because there a lot of discrimination of the leiti's in high school and primary school too. I have been going from school to school for two years. My plan to visit all the schools in Tonga. We mostly go to all-boys schools is because discrimination in school is mostly done by boys. I was very happy last year when I went to a boys school and so how they really appreciate the work and how well they treated the Leiti's in the school." In February, Tonga was hit by tropical cyclone Gita, the worst cyclone to hit the island in over 60 years. Leilani worries that not enough is being done to ensure the needs of the Leiti and LGBTI+ community is being met during and post humanitarian disasters. "We are one of the vulnerable groups, after the cyclone Gita we should be one of the first priority for the government, or the hospital or any donations. Cause our life is very unique and we are easy to harm." Despite the hardships surrounding the leiti community, Leilani is hopeful for the future, "I can see a lot of families that now accept leiti's in their house and they treat them well. I have a feeling the future will be better. Please stop discriminating against us, but love us. We are here to stay, we are not here to chase away." Watch the Humanitarian teams response to Cyclone Gita

| 22 January 2018

"I am a living example of having a good life..."

At a local bar, we meet nine women from Kirundo. They’re all sex workers who became friends through Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial's (ABUBEF) peer educator project. Yvonne is 40 and has known that she’s HIV-positive for 22 years. After her diagnosis she was isolated from her friends and stigmatized both in public and at home, where she was even given separate plates to eat from. “I started to get drunk every day,” she says. “I hoped death would take me in my sleep. I didn’t believe in tomorrow. I was lost and lonely. Until I got to the ABUBEF clinic.” ABUBEF has supported her treatment for the past six years. “I take my pill every day and I am living example of having a good life even with a previous death sentence,” Yvonne explains. “But I see that the awareness of HIV, protection and testing provided by ABUBEF is still very small.” Yvonne became a peer educator, speaking in public about HIV awareness, wearing an ABUBEF T-shirt. The project spread to the wider region, and volunteers were given travel expenses, materials and training, along with condoms for distribution. But funding cuts mean those expenses are no longer available. Yvonne says she’ll carry on in Kirundo even if she can’t travel more widely like she used to. Her friend, 29-year-old Perusi, shares her experience of ABUBEF as a safe space where her privacy will be respected. It often happens, she says, that her clients rape her, and run away, failing to pay. Since sex work is illegal, she says, and there’s no protection from the authorities, and sex workers like her often feel rejected by society. But at ABUBEF’s clinics, they are welcomed.

| 16 May 2025

"I am a living example of having a good life..."

At a local bar, we meet nine women from Kirundo. They’re all sex workers who became friends through Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial's (ABUBEF) peer educator project. Yvonne is 40 and has known that she’s HIV-positive for 22 years. After her diagnosis she was isolated from her friends and stigmatized both in public and at home, where she was even given separate plates to eat from. “I started to get drunk every day,” she says. “I hoped death would take me in my sleep. I didn’t believe in tomorrow. I was lost and lonely. Until I got to the ABUBEF clinic.” ABUBEF has supported her treatment for the past six years. “I take my pill every day and I am living example of having a good life even with a previous death sentence,” Yvonne explains. “But I see that the awareness of HIV, protection and testing provided by ABUBEF is still very small.” Yvonne became a peer educator, speaking in public about HIV awareness, wearing an ABUBEF T-shirt. The project spread to the wider region, and volunteers were given travel expenses, materials and training, along with condoms for distribution. But funding cuts mean those expenses are no longer available. Yvonne says she’ll carry on in Kirundo even if she can’t travel more widely like she used to. Her friend, 29-year-old Perusi, shares her experience of ABUBEF as a safe space where her privacy will be respected. It often happens, she says, that her clients rape her, and run away, failing to pay. Since sex work is illegal, she says, and there’s no protection from the authorities, and sex workers like her often feel rejected by society. But at ABUBEF’s clinics, they are welcomed.

| 22 January 2018

“They saved the life of me and my child”

Monica has never told anyone about the attack. She was pregnant at the time, already had two teenage sons, and rape is a taboo subject in her community in Burundi. Knowing that her attacker was HIV-positive, and fearing that her husband would accuse her of provocation - or worse still, leave her - she turned to a place she knew would help. ABUBEF is the Association Burundaise Pour Le Bien-Etre Familial. Their clinic in Kirundo offered Monica HIV counselling and treatment for the duration of her pregnancy. Above all, ABUBEF offered privacy. Neither Monica nor her daughter has tested positive for HIV. “They saved the life of me and my child,” Monica says. “I hope they get an award for their psychological and health support for women.” Three years on from the attack, Monica, now 45, raises her children and tends the family farm where she grows beans, cassava, potatoes and rice. She’s proud of her eldest son who’s due to start university this year. She educates her boys against violence, and spreads the word about ABUBEF. Monica speaks to other women to make sure they know where to seek help if they need it. Her attacker still lives in the neighbourhood, and she worries that he’s transmitting HIV. But the ABUBEF clinic that helped Monica is under threat from funding cuts. The possibility that it could close prompted her to tell her story. “This is a disaster for our community,” she says. “I know how much the clinic needs support from donors, how much they need new equipment and money for new staff. I want people to know that this facility is one of a kind - and without it many people will be lost.”

| 16 May 2025

“They saved the life of me and my child”

Monica has never told anyone about the attack. She was pregnant at the time, already had two teenage sons, and rape is a taboo subject in her community in Burundi. Knowing that her attacker was HIV-positive, and fearing that her husband would accuse her of provocation - or worse still, leave her - she turned to a place she knew would help. ABUBEF is the Association Burundaise Pour Le Bien-Etre Familial. Their clinic in Kirundo offered Monica HIV counselling and treatment for the duration of her pregnancy. Above all, ABUBEF offered privacy. Neither Monica nor her daughter has tested positive for HIV. “They saved the life of me and my child,” Monica says. “I hope they get an award for their psychological and health support for women.” Three years on from the attack, Monica, now 45, raises her children and tends the family farm where she grows beans, cassava, potatoes and rice. She’s proud of her eldest son who’s due to start university this year. She educates her boys against violence, and spreads the word about ABUBEF. Monica speaks to other women to make sure they know where to seek help if they need it. Her attacker still lives in the neighbourhood, and she worries that he’s transmitting HIV. But the ABUBEF clinic that helped Monica is under threat from funding cuts. The possibility that it could close prompted her to tell her story. “This is a disaster for our community,” she says. “I know how much the clinic needs support from donors, how much they need new equipment and money for new staff. I want people to know that this facility is one of a kind - and without it many people will be lost.”

| 19 January 2018

“I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one"

On Friday afternoon in Municipal Lycee of Nyakabiga, Burundi, headmistress Chantal Keza is introducing her students to the medical staff from Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ABUBEF). Peer educators at the school, trained by ABUBEF, will perform a short drama based around sexual health and will answer questions about contraception methods from students. One of the actresses is peer educator Ammande Berlyne Dushime. Ammande, who is 17 years old is one of three peer educators at the school. Ammande, together with her friends, perform their short drama on the stage based on a young girls quest for information on contraception. It ends on a positive note, with the girl receiving useful and correct information from a peer educator at her school. A story that could be a very real life scenario at her school. Peer programmes that trained Ammande, are under threat of closure due to the Global Gag rule. Ammande says, “I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one. I am ready to go on with work as peer educator, but if there are not going to be regular visits by the medical stuff from the clinic, then we will have no one to seek information and advice from. I am just a teenager, I know so little. Not only I will lose my support, but also I will not be taken serious by my schoolmates. With such important topic like sexual education and contraception, I am not the authority. I can only show the right way to go. And this road leads to ABUBEF.” She says “As peer educator I am responsible for Saturday morning meetings at the clinic. We sing songs, play games, have fun and learn new things about sex education, contraception, HIV protection and others. Visiting the clinic is then very easy, and no student has to be afraid, that showing up at the clinic that treats HIV positive people, will ruin their reputation. Now they know that we can meet there openly, and undercover of these meetings seek for help, information, professional advice and contraception methods” Peer educator classes are a safe and open place for students to openly talk about their sexual health. The Global Gage Rule will force peer educator programmes like this to close due to lack of funding. Help us bridge the funding gap Learn more about the Global Gag Rule

| 16 May 2025

“I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one"

On Friday afternoon in Municipal Lycee of Nyakabiga, Burundi, headmistress Chantal Keza is introducing her students to the medical staff from Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ABUBEF). Peer educators at the school, trained by ABUBEF, will perform a short drama based around sexual health and will answer questions about contraception methods from students. One of the actresses is peer educator Ammande Berlyne Dushime. Ammande, who is 17 years old is one of three peer educators at the school. Ammande, together with her friends, perform their short drama on the stage based on a young girls quest for information on contraception. It ends on a positive note, with the girl receiving useful and correct information from a peer educator at her school. A story that could be a very real life scenario at her school. Peer programmes that trained Ammande, are under threat of closure due to the Global Gag rule. Ammande says, “I am afraid what will happen when there will be no more projects like this one. I am ready to go on with work as peer educator, but if there are not going to be regular visits by the medical stuff from the clinic, then we will have no one to seek information and advice from. I am just a teenager, I know so little. Not only I will lose my support, but also I will not be taken serious by my schoolmates. With such important topic like sexual education and contraception, I am not the authority. I can only show the right way to go. And this road leads to ABUBEF.” She says “As peer educator I am responsible for Saturday morning meetings at the clinic. We sing songs, play games, have fun and learn new things about sex education, contraception, HIV protection and others. Visiting the clinic is then very easy, and no student has to be afraid, that showing up at the clinic that treats HIV positive people, will ruin their reputation. Now they know that we can meet there openly, and undercover of these meetings seek for help, information, professional advice and contraception methods” Peer educator classes are a safe and open place for students to openly talk about their sexual health. The Global Gage Rule will force peer educator programmes like this to close due to lack of funding. Help us bridge the funding gap Learn more about the Global Gag Rule