Spotlight

A selection of stories from across the Federation

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in the face of growing opposition and the rise of the far right? These victories for sexual and reproductive rights and health are the result of relentless grassroots work and advocacy by our Member Associations, in partnership with community organizations, allied politicians, and the mobilization of public opinion.

Most Popular This Week

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in t

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan's Rising HIV Crisis: A Call for Action

On World AIDS Day, we commemorate the remarkable achievements of IPPF Member Associations in their unwavering commitment to combating the HIV epidemic.

Ensuring SRHR in Humanitarian Crises: What You Need to Know

Over the past two decades, global forced displacement has consistently increased, affecting an estimated 114 million people as of mid-2023.

Estonia, Nepal, Namibia, Japan, Thailand

The Rainbow Wave for Marriage Equality

Love wins! The fight for marriage equality has seen incredible progress worldwide, with a recent surge in legalizations.

France, Germany, Poland, United Kingdom, United States, Colombia, India, Tunisia

Abortion Rights: Latest Decisions and Developments around the World

Over the past 30 years, more than

Palestine

In their own words: The people providing sexual and reproductive health care under bombardment in Gaza

Week after week, heavy Israeli bombardment from air, land, and sea, has continued across most of the Gaza Strip.

Vanuatu

When getting to the hospital is difficult, Vanuatu mobile outreach can save lives

In the mountains of Kumera on Tanna Island, Vanuatu, the village women of Kamahaul normally spend over 10,000 Vatu ($83 USD) to travel to the nearest hospital.

Filter our stories by:

- Afghan Family Guidance Association

- Albanian Center for Population and Development

- Asociación Pro-Bienestar de la Familia Colombiana

- Associação Moçambicana para Desenvolvimento da Família

- Association Béninoise pour la Promotion de la Famille

- Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial

- (-) Association Malienne pour la Protection et la Promotion de la Famille

- Association pour le Bien-Etre Familial/Naissances Désirables

- Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Étre Familial

- Association Togolaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial

- Association Tunisienne de la Santé de la Reproduction

- Botswana Family Welfare Association

- Cameroon National Association for Family Welfare

- Cook Islands Family Welfare Association

- Eesti Seksuaaltervise Liit / Estonian Sexual Health Association

- Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia

- Family Planning Association of India

- Family Planning Association of Malawi

- Family Planning Association of Nepal

- Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka

- Family Planning Association of Trinidad and Tobago

- Foundation for the Promotion of Responsible Parenthood - Aruba

- Indonesian Planned Parenthood Association

- Jamaica Family Planning Association

- Kazakhstan Association on Sexual and Reproductive Health (KMPA)

- Kiribati Family Health Association

- Lesotho Planned Parenthood Association

- Mouvement Français pour le Planning Familial

- Palestinian Family Planning and Protection Association (PFPPA)

- (-) Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana

- Planned Parenthood Association of Thailand

- Planned Parenthood Association of Zambia

- Planned Parenthood Federation of America

- Planned Parenthood Federation of Nigeria

- Pro Familia - Germany

- Rahnuma-Family Planning Association of Pakistan

- Reproductive & Family Health Association of Fiji

- Reproductive Health Association of Cambodia (RHAC)

- Reproductive Health Uganda

- Somaliland Family Health Association

- Sudan Family Planning Association

- Tonga Family Health Association

- Vanuatu Family Health Association

| 08 January 2021

"Girls have to know their rights"

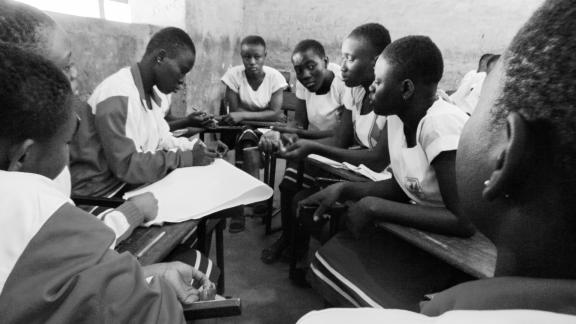

Aminata Sonogo listened intently to the group of young volunteers as they explained different types of contraception, and raised her hand with questions. Sitting at a wooden school desk at 22, Aminata is older than most of her classmates, but she shrugs off the looks and comments. She has fought hard to be here. Aminata is studying in Bamako, the capital of Mali. Just a quarter of Malian girls complete secondary school, according to UNICEF. But even if she will graduate later than most, Aminata is conscious of how far she has come. “I wanted to go to high school but I needed to pass some exams to get here. In the end, it took me three years,” she said. At the start of her final year of collège, or middle school, Aminata got pregnant. She is far from alone: 38% of Malian girls will be pregnant or a mother by the age of 18. Abortion is illegal in Mali except in cases of rape, incest or danger to the mother’s life, and even then it is difficult to obtain, according to medical professionals. Determined to take control of her life “I felt a lot of stigma from my classmates and even my teachers. I tried to ignore them and carry on going to school and studying. But I gave birth to my daughter just before my exams, so I couldn’t take them.” Aminata went through her pregnancy with little support, as the father of her daughter, Fatoumata, distanced himself from her after arguments about their situation. “I have had some problems with the father of the baby. We fought a lot and I didn’t see him for most of the pregnancy, right until the birth,” she recalled. The first year of her daughter’s life was a blur of doctors’ appointments, as Fatoumata was often ill. It seemed Aminata’s chances of finishing school were slipping away. But gradually her family began to take a more active role in caring for her daughter, and she began demanding more help from Fatoumata’s father too. She went back to school in the autumn, 18 months after Fatoumata’s birth and with more determination than ever. She no longer had time to hang out with friends after school, but attended classes, took care of her daughter and then studied more. At the end of the academic year, it paid off. “I did it. I passed my exams and now I am in high school,” Aminata said, smiling and relaxing her shoulders. "Family planning protects girls" Aminata’s next goal is her high school diploma, and obtaining it while trying to navigate the difficult world of relationships and sex. “It’s something you can talk about with your close friends. I would be too ashamed to talk about this with my parents,” she said. She is guided by visits from the young volunteers of the Association Malienne pour la Protection et Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), and shares her own story with classmates who she sees at risk. “The guys come up to you and tell you that you are beautiful, but if you don’t want to sleep with them they will rape you. That’s the choice. You can accept or you can refuse and they will rape you anyway,” she said. “Girls have to know their rights”. After listening to the volunteers talk about all the different options for contraception, she is reviewing her own choices. “Family planning protects girls,” Aminata said. “It means we can protect ourselves from pregnancies that we don’t want”.

| 15 May 2025

"Girls have to know their rights"

Aminata Sonogo listened intently to the group of young volunteers as they explained different types of contraception, and raised her hand with questions. Sitting at a wooden school desk at 22, Aminata is older than most of her classmates, but she shrugs off the looks and comments. She has fought hard to be here. Aminata is studying in Bamako, the capital of Mali. Just a quarter of Malian girls complete secondary school, according to UNICEF. But even if she will graduate later than most, Aminata is conscious of how far she has come. “I wanted to go to high school but I needed to pass some exams to get here. In the end, it took me three years,” she said. At the start of her final year of collège, or middle school, Aminata got pregnant. She is far from alone: 38% of Malian girls will be pregnant or a mother by the age of 18. Abortion is illegal in Mali except in cases of rape, incest or danger to the mother’s life, and even then it is difficult to obtain, according to medical professionals. Determined to take control of her life “I felt a lot of stigma from my classmates and even my teachers. I tried to ignore them and carry on going to school and studying. But I gave birth to my daughter just before my exams, so I couldn’t take them.” Aminata went through her pregnancy with little support, as the father of her daughter, Fatoumata, distanced himself from her after arguments about their situation. “I have had some problems with the father of the baby. We fought a lot and I didn’t see him for most of the pregnancy, right until the birth,” she recalled. The first year of her daughter’s life was a blur of doctors’ appointments, as Fatoumata was often ill. It seemed Aminata’s chances of finishing school were slipping away. But gradually her family began to take a more active role in caring for her daughter, and she began demanding more help from Fatoumata’s father too. She went back to school in the autumn, 18 months after Fatoumata’s birth and with more determination than ever. She no longer had time to hang out with friends after school, but attended classes, took care of her daughter and then studied more. At the end of the academic year, it paid off. “I did it. I passed my exams and now I am in high school,” Aminata said, smiling and relaxing her shoulders. "Family planning protects girls" Aminata’s next goal is her high school diploma, and obtaining it while trying to navigate the difficult world of relationships and sex. “It’s something you can talk about with your close friends. I would be too ashamed to talk about this with my parents,” she said. She is guided by visits from the young volunteers of the Association Malienne pour la Protection et Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), and shares her own story with classmates who she sees at risk. “The guys come up to you and tell you that you are beautiful, but if you don’t want to sleep with them they will rape you. That’s the choice. You can accept or you can refuse and they will rape you anyway,” she said. “Girls have to know their rights”. After listening to the volunteers talk about all the different options for contraception, she is reviewing her own choices. “Family planning protects girls,” Aminata said. “It means we can protect ourselves from pregnancies that we don’t want”.

| 08 January 2021

"We see cases of early pregnancy from 14 years old – occasionally they are younger"

My name is Mariame Doumbia, I am a midwife with the Association Malienne pour la Protection et la Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), providing family planning and sexual health services to Malians in and around the capital, Bamako. I have worked with AMPPF for almost six years in total, but there was a break two years ago when American funding stopped due to the Global Gag Rule. I was able to come back to work with Canadian funding for the project SheDecides, and they have paid my salary for the last two years. I work at fixed and mobile clinics in Bamako. In the neighbourhood of Kalabancoro, which is on the outskirts of the capital, I receive clients at the clinic who would not be able to afford travel to somewhere farther away. It’s a poor neighbourhood. Providing the correct information The women come with their ideas about sex, sometimes with lots of rumours, but we go through it all with them to explain what sexual health is and how to maintain it. We clarify things for them. More and more they come with their mothers, or their boyfriends or husbands. The youngest ones come to ask about their periods and how they can count their menstrual cycle. Then they start to ask about sex. These days the price of sanitary pads is going down, so they are using bits of fabric less often, which is what I used to see. Seeing the impact of our work We see cases of early pregnancy here in Kalabancoro, but the numbers are definitely going down. Most are from 14 years old upwards, though occasionally they are younger. SheDecides has brought so much to this clinic, starting with the fact that before the project’s arrival there was no one here at all for a prolonged period of time. Now the community has the right to information and I try my best to answer all their questions.

| 15 May 2025

"We see cases of early pregnancy from 14 years old – occasionally they are younger"

My name is Mariame Doumbia, I am a midwife with the Association Malienne pour la Protection et la Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), providing family planning and sexual health services to Malians in and around the capital, Bamako. I have worked with AMPPF for almost six years in total, but there was a break two years ago when American funding stopped due to the Global Gag Rule. I was able to come back to work with Canadian funding for the project SheDecides, and they have paid my salary for the last two years. I work at fixed and mobile clinics in Bamako. In the neighbourhood of Kalabancoro, which is on the outskirts of the capital, I receive clients at the clinic who would not be able to afford travel to somewhere farther away. It’s a poor neighbourhood. Providing the correct information The women come with their ideas about sex, sometimes with lots of rumours, but we go through it all with them to explain what sexual health is and how to maintain it. We clarify things for them. More and more they come with their mothers, or their boyfriends or husbands. The youngest ones come to ask about their periods and how they can count their menstrual cycle. Then they start to ask about sex. These days the price of sanitary pads is going down, so they are using bits of fabric less often, which is what I used to see. Seeing the impact of our work We see cases of early pregnancy here in Kalabancoro, but the numbers are definitely going down. Most are from 14 years old upwards, though occasionally they are younger. SheDecides has brought so much to this clinic, starting with the fact that before the project’s arrival there was no one here at all for a prolonged period of time. Now the community has the right to information and I try my best to answer all their questions.

| 08 January 2021

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 15 May 2025

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 07 January 2021

In pictures: Overcoming the impact of the Global Gag Rule in Mali

In 2017, the Association Malienne pour la Protection et la Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), was hit hard by the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR). The impact was swift and devastating – depleted budgets meant that AMPPF had to cut back on key staff and suspend education activities and community healthcare provision. The situation turned around with funding from the Canadian Government supporting the SheDecides project, filling the gap left by GGR. AMPPF has been able to employ staff ensuring their team can reach the most vulnerable clients who would otherwise be left without access to sexual healthcare and increase their outreach to youth. Putting communities first Mama Keita Sy Diallo, midwife The SheDecides project has allowed AMPPF to maintain three mobile clinics, travelling to more remote areas where transportation costs and huge distances separate women from access to health and contraceptive care.“SheDecides has helped us a lot, above all in our work outside our own permanent clinics. When we go out in the community we have a lot of clients, and many women come to us who would otherwise not have the means to obtain advice or contraception,” explained Mama Keita Sy Diallo, a midwife and AMPPF board member. She runs consultations at community health centers in underserved areas of the Malian capital. “Everything is free for the women in these sessions.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email SheDecides projects ensures free access to healthcare and contraception Fatoumata Dramé, client By 9am at the Asaco Sekasi community health center in Bamako, its wooden benches are full of clients waiting their turn at a SheDecides outreach session. Fatoumata Dramé, 30, got here early and has already been fitted for a new implant. “I came here for family planning, and it’s my first time. I’ve just moved to the area so I came because it’s close to home,” she said. Bouncing two-month-old Tiemoko on her knee, Dramé said her main motivation was to space the births of her children. “I am a mum of three now. My first child is 7 years old. I try to leave three years between each child. It helps with my health,” she explained. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Targeting youth Mamadou Bah, Youth Action Movement “After the arrival of SheDecides, we intensified our targeting of vulnerable groups with activities in the evening, when domestic workers and those working during the day could attend,” said Mariam Modibo Tandina, who heads the national committee of the Youth Action Movement in Mali. “That means that young people in precarious situations could learn more about safer sex and family planning. Now they know how to protect themselves against sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Speaking out against FGM Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga, youth volunteer Fatoumata’s decision to join the Youth Action Movement was fueled by a personal loss. “My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Using dance and comedy to talk about sex Abdoulaye Camara, Head of AMPPF dance troupe Abdoulaye’s moves are not just for fun. He is head of the dance troupe of the AMPPF’s Youth Action Movement, which uses dance and comedy sketches to talk about sex. It’s a canny way to deliver messages about everything from using condoms to taking counterfeit antibiotics, to an audience who are often confused and ashamed about such topics. “We distract them with dance and humour and then we transmit those important messages about sex without offending them,” explained Abdoulaye. “We show them that it’s not to insult them or show them up, but just to explain how these things happen.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Determination to graduate Aminata Sonogo, student Sitting at a wooden school desk at 22, Sonogo is older than most of her classmates, but she shrugs off the looks and comments. She has fought hard to be here. “I wanted to go to high school but I needed to pass some exams to get here. In the end, it took me three years,” she said.At the start of her final year of collège, or middle school, Sonogo got pregnant. She went back to school in the autumn, 18 months after Fatoumata’s birth and with more determination than ever. At the end of the academic year, it paid off. “I did it. I passed my exams and now I am in high school,” Sonogo said, smiling and relaxing her shoulders. She is guided by visits from the AMPPF youth volunteers and shares her own story with classmates who she sees at risk of an unwanted pregnancy. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email AMPPF’s mobile clinic offers a lifeline to remote communities Mariame Doumbia, midwife “I work at a mobile clinic. It’s important for accessibility, so that the women living in poorly serviced areas can access sexual and reproductive health services, and reliable information.I like what I do. I like helping people, especially the young ones. They know I am always on call to help them, and even if I don’t know the answer at that moment, I will find out. I like everything about my work. Actually, it’s not just work for me, and I became a midwife for that reason. I’ve always been an educator on these issues in my community.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Trust underpins the relationship between AMPPF’s mobile team and the village of Missala Adama Samaké, village elder and chief of the Missala Health Center Adama Samaké, chief of the Missala Health Center, oversees the proceedings as a village elder with deep trust from his community. When the mobile clinic isn’t around, his center offers maternity services and treats the many cases of malaria that are diagnosed in the community. “Given the distance between here and Bamako, most of the villagers around here rely on us for treatment,” he said. “But when we announce that the mobile clinic is coming, the women make sure they are here.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Contraceptive choice Kadidiatou Sogoba, client Kadidiatou Sogoba, a mother of seven, waited nervously for her turn. “I came today because I keep getting ill and I have felt very weak, just not myself, since I had a Caesarean section three years ago. I lost a lot of blood,” she said. “I have been very afraid since the birth of my last child. We have been using condoms and we were getting a bit tired of them, so I am looking for another longer-term type of contraception.”After emerging half an hour later, Sogoba clutched a packet of the contraceptive pill, and said next time she would go for a cervical screening.Photos ©IPPF/Xaume Olleros/Mali Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email

| 16 May 2025

In pictures: Overcoming the impact of the Global Gag Rule in Mali

In 2017, the Association Malienne pour la Protection et la Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), was hit hard by the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR). The impact was swift and devastating – depleted budgets meant that AMPPF had to cut back on key staff and suspend education activities and community healthcare provision. The situation turned around with funding from the Canadian Government supporting the SheDecides project, filling the gap left by GGR. AMPPF has been able to employ staff ensuring their team can reach the most vulnerable clients who would otherwise be left without access to sexual healthcare and increase their outreach to youth. Putting communities first Mama Keita Sy Diallo, midwife The SheDecides project has allowed AMPPF to maintain three mobile clinics, travelling to more remote areas where transportation costs and huge distances separate women from access to health and contraceptive care.“SheDecides has helped us a lot, above all in our work outside our own permanent clinics. When we go out in the community we have a lot of clients, and many women come to us who would otherwise not have the means to obtain advice or contraception,” explained Mama Keita Sy Diallo, a midwife and AMPPF board member. She runs consultations at community health centers in underserved areas of the Malian capital. “Everything is free for the women in these sessions.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email SheDecides projects ensures free access to healthcare and contraception Fatoumata Dramé, client By 9am at the Asaco Sekasi community health center in Bamako, its wooden benches are full of clients waiting their turn at a SheDecides outreach session. Fatoumata Dramé, 30, got here early and has already been fitted for a new implant. “I came here for family planning, and it’s my first time. I’ve just moved to the area so I came because it’s close to home,” she said. Bouncing two-month-old Tiemoko on her knee, Dramé said her main motivation was to space the births of her children. “I am a mum of three now. My first child is 7 years old. I try to leave three years between each child. It helps with my health,” she explained. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Targeting youth Mamadou Bah, Youth Action Movement “After the arrival of SheDecides, we intensified our targeting of vulnerable groups with activities in the evening, when domestic workers and those working during the day could attend,” said Mariam Modibo Tandina, who heads the national committee of the Youth Action Movement in Mali. “That means that young people in precarious situations could learn more about safer sex and family planning. Now they know how to protect themselves against sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Speaking out against FGM Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga, youth volunteer Fatoumata’s decision to join the Youth Action Movement was fueled by a personal loss. “My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Using dance and comedy to talk about sex Abdoulaye Camara, Head of AMPPF dance troupe Abdoulaye’s moves are not just for fun. He is head of the dance troupe of the AMPPF’s Youth Action Movement, which uses dance and comedy sketches to talk about sex. It’s a canny way to deliver messages about everything from using condoms to taking counterfeit antibiotics, to an audience who are often confused and ashamed about such topics. “We distract them with dance and humour and then we transmit those important messages about sex without offending them,” explained Abdoulaye. “We show them that it’s not to insult them or show them up, but just to explain how these things happen.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Determination to graduate Aminata Sonogo, student Sitting at a wooden school desk at 22, Sonogo is older than most of her classmates, but she shrugs off the looks and comments. She has fought hard to be here. “I wanted to go to high school but I needed to pass some exams to get here. In the end, it took me three years,” she said.At the start of her final year of collège, or middle school, Sonogo got pregnant. She went back to school in the autumn, 18 months after Fatoumata’s birth and with more determination than ever. At the end of the academic year, it paid off. “I did it. I passed my exams and now I am in high school,” Sonogo said, smiling and relaxing her shoulders. She is guided by visits from the AMPPF youth volunteers and shares her own story with classmates who she sees at risk of an unwanted pregnancy. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email AMPPF’s mobile clinic offers a lifeline to remote communities Mariame Doumbia, midwife “I work at a mobile clinic. It’s important for accessibility, so that the women living in poorly serviced areas can access sexual and reproductive health services, and reliable information.I like what I do. I like helping people, especially the young ones. They know I am always on call to help them, and even if I don’t know the answer at that moment, I will find out. I like everything about my work. Actually, it’s not just work for me, and I became a midwife for that reason. I’ve always been an educator on these issues in my community.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Trust underpins the relationship between AMPPF’s mobile team and the village of Missala Adama Samaké, village elder and chief of the Missala Health Center Adama Samaké, chief of the Missala Health Center, oversees the proceedings as a village elder with deep trust from his community. When the mobile clinic isn’t around, his center offers maternity services and treats the many cases of malaria that are diagnosed in the community. “Given the distance between here and Bamako, most of the villagers around here rely on us for treatment,” he said. “But when we announce that the mobile clinic is coming, the women make sure they are here.” Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Contraceptive choice Kadidiatou Sogoba, client Kadidiatou Sogoba, a mother of seven, waited nervously for her turn. “I came today because I keep getting ill and I have felt very weak, just not myself, since I had a Caesarean section three years ago. I lost a lot of blood,” she said. “I have been very afraid since the birth of my last child. We have been using condoms and we were getting a bit tired of them, so I am looking for another longer-term type of contraception.”After emerging half an hour later, Sogoba clutched a packet of the contraceptive pill, and said next time she would go for a cervical screening.Photos ©IPPF/Xaume Olleros/Mali Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email

| 20 February 2020

“Teenage pregnancies will decrease, unsafe abortions and deaths as a result of unsafe abortions will decrease"

Midwife Sophia Abrafi sits at her desk, sorting her paperwork before another patient comes in looking for family planning services. The 40-year-old midwife welcomes each patient with a warm smile and when she talks, her passion for her work is clear. At the Mim Health Centre, which is located in the Ahafo Region of Ghana, Abrafi says a sexual and reproductive health and right (SRHR) project through Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG) and the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA) allows her to offer comprehensive SRH services to those in the community, especially young people. Before the project, launched in 2018, she used to have to refer people to a town about 20 minutes away for comprehensive abortion care. She had also seen many women coming in for post abortion care service after trying to self-administer an abortion. “It was causing a lot of harm in this community...those cases were a lot, they will get pregnant, and they themselves will try to abort.” Providing care & services to young people Through the clinic, she speaks to young people about their sexual and reproductive health and rights. “Those who can’t [abstain] we offer them family planning services, so at least they can complete their schooling.” Offering these services is crucial in Mim, she says, because often young people are not aware of sexual and reproductive health risks. “Some of them will even get pregnant in the first attempt, so at least explaining to the person what it is, what she should do, or what she should expect in that stage -is very helpful.” She has already seen progress. “The young ones are coming. If the first one will come and you provide the service, she will go and inform the friends, and the friends will come.” Hairdresser Jennifer Osei, who is waiting to see Abrafi, is a testament to this. She did not learn about family planning at school. After a friend told her about the clinic, she has begun relying on staff like Abrafi to educate her. “I have come to take a family planning injection, it is my first time taking the injection. I have given birth to one child, and I don’t want to have many children now,” she says. Expanding services in Mim The SRHR project is working in three other clinics or health centres in Mim, including at the Ahmadiyya Muslim Hospital. When midwife Sherifa, 28, heard about the SRHR project coming to Mim, she knew it would help her hospital better help the community. The hospital was only offering care for pregnancy complications and did little family planning work. Now, it is supplied with a range of family planning commodities, and the ability to do comprehensive abortion care, as well as education on SRHR. Being able to offer these services especially helps school girls to prevent unintended pregnancies and to continue at school, she says. Sherifa also already sees success from this project, with young people now coming in for services, education and treatment of STIs. In the long term, she predicts many positive changes. “STI infection rates will decrease, teenage pregnancies will decrease, unsafe abortions and deaths as a result of unsafe abortions will decrease. The young people will now have more information about their sexual life in this community, as a result of the project.”

| 15 May 2025

“Teenage pregnancies will decrease, unsafe abortions and deaths as a result of unsafe abortions will decrease"

Midwife Sophia Abrafi sits at her desk, sorting her paperwork before another patient comes in looking for family planning services. The 40-year-old midwife welcomes each patient with a warm smile and when she talks, her passion for her work is clear. At the Mim Health Centre, which is located in the Ahafo Region of Ghana, Abrafi says a sexual and reproductive health and right (SRHR) project through Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG) and the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA) allows her to offer comprehensive SRH services to those in the community, especially young people. Before the project, launched in 2018, she used to have to refer people to a town about 20 minutes away for comprehensive abortion care. She had also seen many women coming in for post abortion care service after trying to self-administer an abortion. “It was causing a lot of harm in this community...those cases were a lot, they will get pregnant, and they themselves will try to abort.” Providing care & services to young people Through the clinic, she speaks to young people about their sexual and reproductive health and rights. “Those who can’t [abstain] we offer them family planning services, so at least they can complete their schooling.” Offering these services is crucial in Mim, she says, because often young people are not aware of sexual and reproductive health risks. “Some of them will even get pregnant in the first attempt, so at least explaining to the person what it is, what she should do, or what she should expect in that stage -is very helpful.” She has already seen progress. “The young ones are coming. If the first one will come and you provide the service, she will go and inform the friends, and the friends will come.” Hairdresser Jennifer Osei, who is waiting to see Abrafi, is a testament to this. She did not learn about family planning at school. After a friend told her about the clinic, she has begun relying on staff like Abrafi to educate her. “I have come to take a family planning injection, it is my first time taking the injection. I have given birth to one child, and I don’t want to have many children now,” she says. Expanding services in Mim The SRHR project is working in three other clinics or health centres in Mim, including at the Ahmadiyya Muslim Hospital. When midwife Sherifa, 28, heard about the SRHR project coming to Mim, she knew it would help her hospital better help the community. The hospital was only offering care for pregnancy complications and did little family planning work. Now, it is supplied with a range of family planning commodities, and the ability to do comprehensive abortion care, as well as education on SRHR. Being able to offer these services especially helps school girls to prevent unintended pregnancies and to continue at school, she says. Sherifa also already sees success from this project, with young people now coming in for services, education and treatment of STIs. In the long term, she predicts many positive changes. “STI infection rates will decrease, teenage pregnancies will decrease, unsafe abortions and deaths as a result of unsafe abortions will decrease. The young people will now have more information about their sexual life in this community, as a result of the project.”

| 20 February 2020

"It has helped me a lot, without that information I would have given birth to many children..."

Factory workers at Mim Cashew, in a small town in rural Ghana, are taking their reproductive health choices into their own hands, thanks to a four-year project rolled out by Planned Parenthood Association Ghana (PPAG) along with the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA). The project, supported by private funding, focuses on factory workers as well as residents in the township of about 30, 000, where the factory is located. Under the project, health clinic staff in Mim have been supported to provide comprehensive abortion care, a range of different contraception choices and STI treatments as well as information and education. In both the community and the factory, there is a strong focus on SRHR trained peer educators delivering information to their colleagues and peers. An increase in knowledge So far, the project has yielded positive results - especially a notable increase amongst the workers on SRHR knowledge and access to services - like worker Janet Pinamang, who is a 32-year-old mother of two. She says the SRHR project has been great for her and her colleagues. "I have had a lot of benefits with the project from PPAG. PPAG has educated us on how the process is involved in a lady becoming pregnant. PPAG has also helped us to understand more on drug abuse and about HIV.” She also appreciated the project working in the wider community and helping to address high levels of teenage pregnancy. "I have seen a lot of change before the coming of PPAG little was known about HIV, and its impacts and how it was contracted - now PPAG has made us know how HIV is spread, how it is gotten and all that. PPAG has also got us to know the benefits of spacing our children." “It has helped me a lot” Pinamang's colleague, Sandra Opoku Agyemang, 27, is a mother of a six-year-old girl called Bridget. Agyemang says before the project came to Mim, she had only heard negative information around family planning. "I heard family planning leads to dizziness, it could lead to fatigue, you won't get a regular flow of menses and all that, and I also heard problems with heart attacks. I had heard of these problems, and I was afraid, so after the coming of PPAG, I went into family planning, and I realised all the things people talked about were not wholly true." Now using family planning herself, she says the future is bright for her, and her family. "It has helped me a lot, without that information I would have given birth to many children, not only Bridget. In the future, I plan to add on two [more children], even with the two I am going to plan."

| 15 May 2025

"It has helped me a lot, without that information I would have given birth to many children..."

Factory workers at Mim Cashew, in a small town in rural Ghana, are taking their reproductive health choices into their own hands, thanks to a four-year project rolled out by Planned Parenthood Association Ghana (PPAG) along with the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA). The project, supported by private funding, focuses on factory workers as well as residents in the township of about 30, 000, where the factory is located. Under the project, health clinic staff in Mim have been supported to provide comprehensive abortion care, a range of different contraception choices and STI treatments as well as information and education. In both the community and the factory, there is a strong focus on SRHR trained peer educators delivering information to their colleagues and peers. An increase in knowledge So far, the project has yielded positive results - especially a notable increase amongst the workers on SRHR knowledge and access to services - like worker Janet Pinamang, who is a 32-year-old mother of two. She says the SRHR project has been great for her and her colleagues. "I have had a lot of benefits with the project from PPAG. PPAG has educated us on how the process is involved in a lady becoming pregnant. PPAG has also helped us to understand more on drug abuse and about HIV.” She also appreciated the project working in the wider community and helping to address high levels of teenage pregnancy. "I have seen a lot of change before the coming of PPAG little was known about HIV, and its impacts and how it was contracted - now PPAG has made us know how HIV is spread, how it is gotten and all that. PPAG has also got us to know the benefits of spacing our children." “It has helped me a lot” Pinamang's colleague, Sandra Opoku Agyemang, 27, is a mother of a six-year-old girl called Bridget. Agyemang says before the project came to Mim, she had only heard negative information around family planning. "I heard family planning leads to dizziness, it could lead to fatigue, you won't get a regular flow of menses and all that, and I also heard problems with heart attacks. I had heard of these problems, and I was afraid, so after the coming of PPAG, I went into family planning, and I realised all the things people talked about were not wholly true." Now using family planning herself, she says the future is bright for her, and her family. "It has helped me a lot, without that information I would have given birth to many children, not only Bridget. In the future, I plan to add on two [more children], even with the two I am going to plan."

| 19 February 2020

“Despite all those challenges, I thought it was necessary to stay in school"

When Gifty Anning Agyei was pregnant, her classmates teased her, telling her she should drop out of school. She thought of having an abortion, and at times she says she considered suicide. When her father, Ebenezer Anning Agyei found out about the pregnancy, he was furious and wanted to kick her out of the house and stop supporting her education. Getting the support she needed But with support from Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG) and advice from Ebenezer’s church pastor, Gifty is still in school, and she has a happy baby boy, named after Gifty’s father. Gifty and the baby are living at home, with Gifty’s parents and three of her siblings in Mim, a small town about eight hours drive northwest of Ghana’s capital Accra. “Despite all those challenges, I thought it was necessary to stay in school. I didn’t want any pregnancy to truncate my future,” Gifty says, while her parents nod in proud support. In this area of Ghana, research conducted in 2018 found young people like Gifty had high sexual and reproduce health and rights (SRHR) challenges, with low comprehensive knowledge of SHRH and concerns about high levels of teenage pregnancy. PPAG, along with the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA), launched a four-year project in Mim in 2018 aimed to address these issues. For Gifty, now 17, and her family, this meant support from PPAG, especially from the coordinator of the project in Mim, Abdul- Mumin Abukari. “I met Abdul when I was pregnant. He was very supportive and encouraged me so much even during antenatals he was with me. Through Abdul, PPAG encouraged me so much.” Her mother, Alice, says with support from PPAG her daughter did not have what might have been an unsafe abortion. The parents are also happy that the PPAG project is educating other young people on SRHR and ensuring they have access to services in Mim. Gifty says teenage pregnancy is common in Mim and is glad PPAG is trying to curb the high rates or support those who do give birth to continue their schooling. “It’s not the end of the road” “PPAG’s assistance is critical. There are so many ladies who when they get into the situation of early pregnancy that is the end of the road, but PPAG has made us know it is only a challenge but not the end of the road.” Gifty’s mum Alice says they see baby Ebenezer as one of their children, who they are raising, for now, so GIfty can continue with her schooling. “In the future, she will take on the responsibly more. Now the work is heavy, that is why we have taken it upon ourselves. In the future, when Gifty is well-employed that responsibility is going to be handed over to her, we will be only playing a supporting role.” Alice also says people in the community have commented on their dedication. “When we are out, people praise us for encouraging our daughter and drawing her closer to us and putting her back to school.” Dad Ebenezer smiles as he looks over at his grandson. “We are very happy now.” When she’s not at school or home with the baby, Gifty is doing an apprenticeship, learning to sew to follow her dream of becoming a fashion designer. For her, despite giving birth so young, she has her sights set on finishing her high school education in 2021 and then heading to higher education.

| 15 May 2025

“Despite all those challenges, I thought it was necessary to stay in school"

When Gifty Anning Agyei was pregnant, her classmates teased her, telling her she should drop out of school. She thought of having an abortion, and at times she says she considered suicide. When her father, Ebenezer Anning Agyei found out about the pregnancy, he was furious and wanted to kick her out of the house and stop supporting her education. Getting the support she needed But with support from Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG) and advice from Ebenezer’s church pastor, Gifty is still in school, and she has a happy baby boy, named after Gifty’s father. Gifty and the baby are living at home, with Gifty’s parents and three of her siblings in Mim, a small town about eight hours drive northwest of Ghana’s capital Accra. “Despite all those challenges, I thought it was necessary to stay in school. I didn’t want any pregnancy to truncate my future,” Gifty says, while her parents nod in proud support. In this area of Ghana, research conducted in 2018 found young people like Gifty had high sexual and reproduce health and rights (SRHR) challenges, with low comprehensive knowledge of SHRH and concerns about high levels of teenage pregnancy. PPAG, along with the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA), launched a four-year project in Mim in 2018 aimed to address these issues. For Gifty, now 17, and her family, this meant support from PPAG, especially from the coordinator of the project in Mim, Abdul- Mumin Abukari. “I met Abdul when I was pregnant. He was very supportive and encouraged me so much even during antenatals he was with me. Through Abdul, PPAG encouraged me so much.” Her mother, Alice, says with support from PPAG her daughter did not have what might have been an unsafe abortion. The parents are also happy that the PPAG project is educating other young people on SRHR and ensuring they have access to services in Mim. Gifty says teenage pregnancy is common in Mim and is glad PPAG is trying to curb the high rates or support those who do give birth to continue their schooling. “It’s not the end of the road” “PPAG’s assistance is critical. There are so many ladies who when they get into the situation of early pregnancy that is the end of the road, but PPAG has made us know it is only a challenge but not the end of the road.” Gifty’s mum Alice says they see baby Ebenezer as one of their children, who they are raising, for now, so GIfty can continue with her schooling. “In the future, she will take on the responsibly more. Now the work is heavy, that is why we have taken it upon ourselves. In the future, when Gifty is well-employed that responsibility is going to be handed over to her, we will be only playing a supporting role.” Alice also says people in the community have commented on their dedication. “When we are out, people praise us for encouraging our daughter and drawing her closer to us and putting her back to school.” Dad Ebenezer smiles as he looks over at his grandson. “We are very happy now.” When she’s not at school or home with the baby, Gifty is doing an apprenticeship, learning to sew to follow her dream of becoming a fashion designer. For her, despite giving birth so young, she has her sights set on finishing her high school education in 2021 and then heading to higher education.

| 19 February 2020

"They teach us as to how to avoid STDs and how to space our childbirth"

As the sun rises each morning, Dorcas Amakyewaa leaves her home she shares with her five children and mother and heads to work at a cashew factory. The factory is on the outskirts of Mim, a town in the Ahafo Region of Ghana. Along the streets of the township, people sell secondhand shoes and clothing or provisions from small, colourfully painted wooden shacks. “There are so many problems in town, notable among them [young people], teenage pregnancies and drug abuse,” Amakyewaa says, reflecting on the community of about 30,000 in Ghana. The chance to make a difference In 2018, Amakyewaa was offered a way to help address these issues in Mim, through a sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR) project brought to both the cashew factory and the surrounding community, through the Danish Family Planning Association, and Planned Parenthood Association Ghana (PPAG). Before the project implementation, some staff at the factory were interviewed and surveyed. Findings revealed similar concerns Amakyewaa had, along with the need for comprehensive education, access and information on the right to key SRHR services. The research also found a preference for receiving SRHR information through friends, colleagues or factory health outreach. These findings then led to PPAG training people in the factory to become SRHR peer educators, including Amakyewaa. She now passes on what she has learnt in her training to her colleagues in sessions, where they discuss different SRHR topics. “I guide them to space their births, and I also guide them on the effects of drug abuse.” The project has also increased access to hospitals, she adds. “The people I teach, I have given the numbers of some nurses to them. So that whenever they need the services of the nurses, they call them and meet them straight away.” Access to information One of the women Amakyewaa meets with to discuss sexual and reproductive health is Monica Asare, a mother of two. “I have had a lot of benefits from PPAG. They teach us as to how to avoid STDs and how to space our childbirth. I teach my child about what we are learning. I never had access to this information; it would have helped me a lot, probably I would have been in school.” Amakyewaa also says she didn’t have access to information and services when she was young. If she had, she says she would not have had a child at 17. She takes the information she has learnt, to share with her children and other young people in the community. When she gets home after work, Amakyewaa’s peer education does not stop, she continues. She also continues her teachings when she gets home. “PPAG’s project has been very helpful to me as a mother. When I go home, previously I was not communicating with my children with issues relating to reproduction.” Her 19-year-old daughter, Stella Akrasi, has also benefitted from her mothers training. “I see it to be good. I always share with my friends give them the importance of family planning. If she teaches me something I will have to go and tell them too” she says.

| 15 May 2025

"They teach us as to how to avoid STDs and how to space our childbirth"

As the sun rises each morning, Dorcas Amakyewaa leaves her home she shares with her five children and mother and heads to work at a cashew factory. The factory is on the outskirts of Mim, a town in the Ahafo Region of Ghana. Along the streets of the township, people sell secondhand shoes and clothing or provisions from small, colourfully painted wooden shacks. “There are so many problems in town, notable among them [young people], teenage pregnancies and drug abuse,” Amakyewaa says, reflecting on the community of about 30,000 in Ghana. The chance to make a difference In 2018, Amakyewaa was offered a way to help address these issues in Mim, through a sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR) project brought to both the cashew factory and the surrounding community, through the Danish Family Planning Association, and Planned Parenthood Association Ghana (PPAG). Before the project implementation, some staff at the factory were interviewed and surveyed. Findings revealed similar concerns Amakyewaa had, along with the need for comprehensive education, access and information on the right to key SRHR services. The research also found a preference for receiving SRHR information through friends, colleagues or factory health outreach. These findings then led to PPAG training people in the factory to become SRHR peer educators, including Amakyewaa. She now passes on what she has learnt in her training to her colleagues in sessions, where they discuss different SRHR topics. “I guide them to space their births, and I also guide them on the effects of drug abuse.” The project has also increased access to hospitals, she adds. “The people I teach, I have given the numbers of some nurses to them. So that whenever they need the services of the nurses, they call them and meet them straight away.” Access to information One of the women Amakyewaa meets with to discuss sexual and reproductive health is Monica Asare, a mother of two. “I have had a lot of benefits from PPAG. They teach us as to how to avoid STDs and how to space our childbirth. I teach my child about what we are learning. I never had access to this information; it would have helped me a lot, probably I would have been in school.” Amakyewaa also says she didn’t have access to information and services when she was young. If she had, she says she would not have had a child at 17. She takes the information she has learnt, to share with her children and other young people in the community. When she gets home after work, Amakyewaa’s peer education does not stop, she continues. She also continues her teachings when she gets home. “PPAG’s project has been very helpful to me as a mother. When I go home, previously I was not communicating with my children with issues relating to reproduction.” Her 19-year-old daughter, Stella Akrasi, has also benefitted from her mothers training. “I see it to be good. I always share with my friends give them the importance of family planning. If she teaches me something I will have to go and tell them too” she says.

| 08 January 2021

"Girls have to know their rights"

Aminata Sonogo listened intently to the group of young volunteers as they explained different types of contraception, and raised her hand with questions. Sitting at a wooden school desk at 22, Aminata is older than most of her classmates, but she shrugs off the looks and comments. She has fought hard to be here. Aminata is studying in Bamako, the capital of Mali. Just a quarter of Malian girls complete secondary school, according to UNICEF. But even if she will graduate later than most, Aminata is conscious of how far she has come. “I wanted to go to high school but I needed to pass some exams to get here. In the end, it took me three years,” she said. At the start of her final year of collège, or middle school, Aminata got pregnant. She is far from alone: 38% of Malian girls will be pregnant or a mother by the age of 18. Abortion is illegal in Mali except in cases of rape, incest or danger to the mother’s life, and even then it is difficult to obtain, according to medical professionals. Determined to take control of her life “I felt a lot of stigma from my classmates and even my teachers. I tried to ignore them and carry on going to school and studying. But I gave birth to my daughter just before my exams, so I couldn’t take them.” Aminata went through her pregnancy with little support, as the father of her daughter, Fatoumata, distanced himself from her after arguments about their situation. “I have had some problems with the father of the baby. We fought a lot and I didn’t see him for most of the pregnancy, right until the birth,” she recalled. The first year of her daughter’s life was a blur of doctors’ appointments, as Fatoumata was often ill. It seemed Aminata’s chances of finishing school were slipping away. But gradually her family began to take a more active role in caring for her daughter, and she began demanding more help from Fatoumata’s father too. She went back to school in the autumn, 18 months after Fatoumata’s birth and with more determination than ever. She no longer had time to hang out with friends after school, but attended classes, took care of her daughter and then studied more. At the end of the academic year, it paid off. “I did it. I passed my exams and now I am in high school,” Aminata said, smiling and relaxing her shoulders. "Family planning protects girls" Aminata’s next goal is her high school diploma, and obtaining it while trying to navigate the difficult world of relationships and sex. “It’s something you can talk about with your close friends. I would be too ashamed to talk about this with my parents,” she said. She is guided by visits from the young volunteers of the Association Malienne pour la Protection et Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), and shares her own story with classmates who she sees at risk. “The guys come up to you and tell you that you are beautiful, but if you don’t want to sleep with them they will rape you. That’s the choice. You can accept or you can refuse and they will rape you anyway,” she said. “Girls have to know their rights”. After listening to the volunteers talk about all the different options for contraception, she is reviewing her own choices. “Family planning protects girls,” Aminata said. “It means we can protect ourselves from pregnancies that we don’t want”.

| 15 May 2025

"Girls have to know their rights"

Aminata Sonogo listened intently to the group of young volunteers as they explained different types of contraception, and raised her hand with questions. Sitting at a wooden school desk at 22, Aminata is older than most of her classmates, but she shrugs off the looks and comments. She has fought hard to be here. Aminata is studying in Bamako, the capital of Mali. Just a quarter of Malian girls complete secondary school, according to UNICEF. But even if she will graduate later than most, Aminata is conscious of how far she has come. “I wanted to go to high school but I needed to pass some exams to get here. In the end, it took me three years,” she said. At the start of her final year of collège, or middle school, Aminata got pregnant. She is far from alone: 38% of Malian girls will be pregnant or a mother by the age of 18. Abortion is illegal in Mali except in cases of rape, incest or danger to the mother’s life, and even then it is difficult to obtain, according to medical professionals. Determined to take control of her life “I felt a lot of stigma from my classmates and even my teachers. I tried to ignore them and carry on going to school and studying. But I gave birth to my daughter just before my exams, so I couldn’t take them.” Aminata went through her pregnancy with little support, as the father of her daughter, Fatoumata, distanced himself from her after arguments about their situation. “I have had some problems with the father of the baby. We fought a lot and I didn’t see him for most of the pregnancy, right until the birth,” she recalled. The first year of her daughter’s life was a blur of doctors’ appointments, as Fatoumata was often ill. It seemed Aminata’s chances of finishing school were slipping away. But gradually her family began to take a more active role in caring for her daughter, and she began demanding more help from Fatoumata’s father too. She went back to school in the autumn, 18 months after Fatoumata’s birth and with more determination than ever. She no longer had time to hang out with friends after school, but attended classes, took care of her daughter and then studied more. At the end of the academic year, it paid off. “I did it. I passed my exams and now I am in high school,” Aminata said, smiling and relaxing her shoulders. "Family planning protects girls" Aminata’s next goal is her high school diploma, and obtaining it while trying to navigate the difficult world of relationships and sex. “It’s something you can talk about with your close friends. I would be too ashamed to talk about this with my parents,” she said. She is guided by visits from the young volunteers of the Association Malienne pour la Protection et Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), and shares her own story with classmates who she sees at risk. “The guys come up to you and tell you that you are beautiful, but if you don’t want to sleep with them they will rape you. That’s the choice. You can accept or you can refuse and they will rape you anyway,” she said. “Girls have to know their rights”. After listening to the volunteers talk about all the different options for contraception, she is reviewing her own choices. “Family planning protects girls,” Aminata said. “It means we can protect ourselves from pregnancies that we don’t want”.

| 08 January 2021

"We see cases of early pregnancy from 14 years old – occasionally they are younger"

My name is Mariame Doumbia, I am a midwife with the Association Malienne pour la Protection et la Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), providing family planning and sexual health services to Malians in and around the capital, Bamako. I have worked with AMPPF for almost six years in total, but there was a break two years ago when American funding stopped due to the Global Gag Rule. I was able to come back to work with Canadian funding for the project SheDecides, and they have paid my salary for the last two years. I work at fixed and mobile clinics in Bamako. In the neighbourhood of Kalabancoro, which is on the outskirts of the capital, I receive clients at the clinic who would not be able to afford travel to somewhere farther away. It’s a poor neighbourhood. Providing the correct information The women come with their ideas about sex, sometimes with lots of rumours, but we go through it all with them to explain what sexual health is and how to maintain it. We clarify things for them. More and more they come with their mothers, or their boyfriends or husbands. The youngest ones come to ask about their periods and how they can count their menstrual cycle. Then they start to ask about sex. These days the price of sanitary pads is going down, so they are using bits of fabric less often, which is what I used to see. Seeing the impact of our work We see cases of early pregnancy here in Kalabancoro, but the numbers are definitely going down. Most are from 14 years old upwards, though occasionally they are younger. SheDecides has brought so much to this clinic, starting with the fact that before the project’s arrival there was no one here at all for a prolonged period of time. Now the community has the right to information and I try my best to answer all their questions.

| 15 May 2025

"We see cases of early pregnancy from 14 years old – occasionally they are younger"

My name is Mariame Doumbia, I am a midwife with the Association Malienne pour la Protection et la Promotion de la Famille (AMPPF), providing family planning and sexual health services to Malians in and around the capital, Bamako. I have worked with AMPPF for almost six years in total, but there was a break two years ago when American funding stopped due to the Global Gag Rule. I was able to come back to work with Canadian funding for the project SheDecides, and they have paid my salary for the last two years. I work at fixed and mobile clinics in Bamako. In the neighbourhood of Kalabancoro, which is on the outskirts of the capital, I receive clients at the clinic who would not be able to afford travel to somewhere farther away. It’s a poor neighbourhood. Providing the correct information The women come with their ideas about sex, sometimes with lots of rumours, but we go through it all with them to explain what sexual health is and how to maintain it. We clarify things for them. More and more they come with their mothers, or their boyfriends or husbands. The youngest ones come to ask about their periods and how they can count their menstrual cycle. Then they start to ask about sex. These days the price of sanitary pads is going down, so they are using bits of fabric less often, which is what I used to see. Seeing the impact of our work We see cases of early pregnancy here in Kalabancoro, but the numbers are definitely going down. Most are from 14 years old upwards, though occasionally they are younger. SheDecides has brought so much to this clinic, starting with the fact that before the project’s arrival there was no one here at all for a prolonged period of time. Now the community has the right to information and I try my best to answer all their questions.

| 08 January 2021

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 15 May 2025

"The movement helps girls to know their rights and their bodies"

My name is Fatoumata Yehiya Maiga. I’m 23-years-old, and I’m an IT specialist. I joined the Youth Action Movement at the end of 2018. The head of the movement in Mali is a friend of mine, and I met her before I knew she was the president. She invited me to their events and over time persuaded me to join. I watched them raising awareness about sexual and reproductive health, using sketches and speeches. I learnt a lot. Overcoming taboos I went home and talked about what I had seen and learnt with my family. In Africa, and even more so in the village where I come from in Gao, northern Mali, people don’t talk about these things. I wanted to take my sisters to the events, but every time I spoke about them my relatives would just say it was to teach girls to have sex, and that it’s taboo. That’s not what I believe. I think the movement helps girls, most of all, to know their sexual rights, their bodies, what to do and what not to do to stay healthy and safe. They don’t understand this concept. My family would say it was just a smokescreen to convince girls to get involved in something dirty. I have had to tell my younger cousins about their periods, for example, when they came from the village to live in the city. One of my cousins was so scared, and told me she was bleeding from her vagina and didn’t know why. We talk about managing periods in the Youth Action Movement, as well as how to manage cramps and feel better. The devastating impact of FGM But there was a much more important reason for me to join the movement. My parents are educated, so me and my sisters were never cut. I learned about female genital mutilation at a conference I attended in 2016. I didn’t know that there were different types of severity and ways that girls could be cut. I hadn’t understood quite how dangerous this practice is. Then, two years ago, I lost my friend Aïssata. She got married young, at 17. She struggled to conceive until she was 23. The day she gave birth, there were complications and she died. The doctors said that the excision was botched and that’s what killed her. From that day on, I decided I needed to teach all the girls in my community about how harmful this practice is for their health. I was so horrified by the way she died. Normally, girls in Mali are cut when they are three or four years old, though for some it’s done at birth. When they are older and get pregnant, I know they face the same challenges as every woman does giving birth, but they also live with the dangerous consequences of this unhealthy practice. The importance of talking openly The problem lies with the families. I want us, as a movement, to talk with the parents and explain to them how they can contribute to their children’s sexual health. I wish it were no longer a taboo between parents and their girls. But if we talk in such direct terms, they only see disobedience, and say that we are encouraging promiscuity. We need to talk to teenagers because they are already parents in many cases. They are the ones who decide to go through with cutting their daughters, or not. A lot of Mali is hard to reach though. We need travelling groups to go to those isolated rural areas and talk to people about sexual health. Pregnancy is the girl’s decision, and girls have a right to be healthy, and to choose their future.

| 07 January 2021

In pictures: Overcoming the impact of the Global Gag Rule in Mali