Spotlight

A selection of stories from across the Federation

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in the face of growing opposition and the rise of the far right? These victories for sexual and reproductive rights and health are the result of relentless grassroots work and advocacy by our Member Associations, in partnership with community organizations, allied politicians, and the mobilization of public opinion.

Most Popular This Week

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in t

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan's Rising HIV Crisis: A Call for Action

On World AIDS Day, we commemorate the remarkable achievements of IPPF Member Associations in their unwavering commitment to combating the HIV epidemic.

Ensuring SRHR in Humanitarian Crises: What You Need to Know

Over the past two decades, global forced displacement has consistently increased, affecting an estimated 114 million people as of mid-2023.

Estonia, Nepal, Namibia, Japan, Thailand

The Rainbow Wave for Marriage Equality

Love wins! The fight for marriage equality has seen incredible progress worldwide, with a recent surge in legalizations.

France, Germany, Poland, United Kingdom, United States, Colombia, India, Tunisia

Abortion Rights: Latest Decisions and Developments around the World

Over the past 30 years, more than

Palestine

In their own words: The people providing sexual and reproductive health care under bombardment in Gaza

Week after week, heavy Israeli bombardment from air, land, and sea, has continued across most of the Gaza Strip.

Vanuatu

When getting to the hospital is difficult, Vanuatu mobile outreach can save lives

In the mountains of Kumera on Tanna Island, Vanuatu, the village women of Kamahaul normally spend over 10,000 Vatu ($83 USD) to travel to the nearest hospital.

Filter our stories by:

- Afghanistan

- Albania

- Aruba

- Bangladesh

- Benin

- Botswana

- Burundi

- Cambodia

- Cameroon

- Colombia

- Congo, Dem. Rep.

- Cook Islands

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Ethiopia

- Fiji

- France

- Germany

- Ghana

- Guinea-Conakry

- India

- Ireland

- Jamaica

- Japan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kiribati

- Lesotho

- Malawi

- Mali

- Mozambique

- Namibia

- Nepal

- Nigeria

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Poland

- (-) Senegal

- Somaliland

- Sri Lanka

- Sudan

- Thailand

- Togo

- Tonga

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Tunisia

- (-) Uganda

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Vanuatu

- Zambia

| 05 January 2022

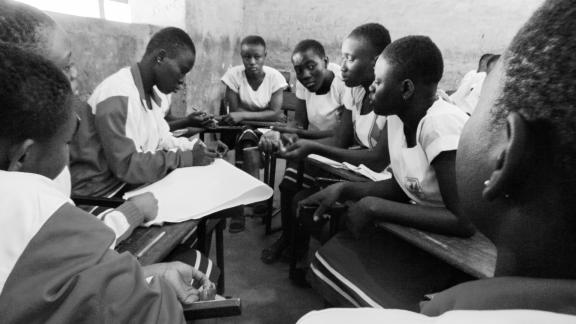

In pictures: The changemaker keeping her community healthy and happy

The Get Up, Speak Out! initiative works with and for young people to overcome barriers such as unequal gender norms, negative attitudes towards sexuality, taboos about sex, menstruation, and abortion. Empowering youth communities - especially girls and young women - with information and knowledge about sexual and reproductive health, and the provision of access to health and contraceptive care, is at the heart of the initiative. Get Up, Speak Out! is an international initiative developed by a consortium of partners including IPPF, Rutgers, CHOICE for Youth & Sexuality, Dance4Life, Simavi, and Aidsfonds, with support from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

| 16 May 2025

In pictures: The changemaker keeping her community healthy and happy

The Get Up, Speak Out! initiative works with and for young people to overcome barriers such as unequal gender norms, negative attitudes towards sexuality, taboos about sex, menstruation, and abortion. Empowering youth communities - especially girls and young women - with information and knowledge about sexual and reproductive health, and the provision of access to health and contraceptive care, is at the heart of the initiative. Get Up, Speak Out! is an international initiative developed by a consortium of partners including IPPF, Rutgers, CHOICE for Youth & Sexuality, Dance4Life, Simavi, and Aidsfonds, with support from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

| 23 January 2019

“Since the closure of the clinic ... we encounter a lot more problems in our area"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Asba Hann is the president of the Guediawaye chapter of IPPF’s Africa region youth action movement. She explains how the Global Gag Rule (GGR) cuts have deprived youth of a space to ask questions about their sexuality and seek advice on contraception. “Since the closure of the clinic, the nature of our advocacy has changed. We encounter a lot more problems in our area, above all from young people and women asking for services. ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial) was a little bit less expensive for them and in this suburb there is a lot of poverty. Our facilities as volunteers also closed. We offer information to young people but since the closure of the clinic and our space they no longer get it in the same way, because they used to come and visit us. We still do activities but it’s difficult to get the information out, so young people worry about their sexual health and can’t get the confirmation needed for their questions. Young people don’t want to be seen going to a pharmacy and getting contraception, at risk of being seen by members of the community. They preferred seeing a midwife, discreetly, and to obtain their contraception privately. Young people often also can’t afford the contraception in the clinics and pharmacies. It would be much easier for us to have a specific place to hold events with the midwives who could then explain things to young people. A lot of the teenagers here still aren’t connected to the internet and active on social media. Others work all day and can’t look at their phones, and announcements get lost when they look at all their messages at night. Being on the ground is the best way for us to connect to young people.”

| 16 May 2025

“Since the closure of the clinic ... we encounter a lot more problems in our area"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Asba Hann is the president of the Guediawaye chapter of IPPF’s Africa region youth action movement. She explains how the Global Gag Rule (GGR) cuts have deprived youth of a space to ask questions about their sexuality and seek advice on contraception. “Since the closure of the clinic, the nature of our advocacy has changed. We encounter a lot more problems in our area, above all from young people and women asking for services. ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial) was a little bit less expensive for them and in this suburb there is a lot of poverty. Our facilities as volunteers also closed. We offer information to young people but since the closure of the clinic and our space they no longer get it in the same way, because they used to come and visit us. We still do activities but it’s difficult to get the information out, so young people worry about their sexual health and can’t get the confirmation needed for their questions. Young people don’t want to be seen going to a pharmacy and getting contraception, at risk of being seen by members of the community. They preferred seeing a midwife, discreetly, and to obtain their contraception privately. Young people often also can’t afford the contraception in the clinics and pharmacies. It would be much easier for us to have a specific place to hold events with the midwives who could then explain things to young people. A lot of the teenagers here still aren’t connected to the internet and active on social media. Others work all day and can’t look at their phones, and announcements get lost when they look at all their messages at night. Being on the ground is the best way for us to connect to young people.”

| 23 January 2019

“Since the clinic closed in this town everything has been very difficult"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Betty Guèye is a midwife who used to live in Guediawaye but moved to Dakar after the closure of the clinic in the suburb of Senegal’s capital following global gag rule (GGR) funding cuts. She describes the effects of the closure and how Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) staff try to maximise the reduced service they still offer. “Since the clinic closed in this town everything has been very difficult. The majority of Senegalese are poor and we are losing clients because they cannot access the main clinic in Dakar. If they have an appointment on a Monday, after the weekend they won’t have the 200 francs (35 US cents) needed for the bus, and they will wait until Tuesday or Wednesday to come even though they are in pain. The clinic was of huge benefit to the community of Guediawaye and the surrounding suburbs as well. What we see now is that women wait until pain or infections are at a more advanced stage before they visit us in Dakar. Another effect is that if they need to update their contraception they will exceed the date required for the new injection or pill and then get pregnant as a result. In addition, raising awareness of sexual health in schools and neighbourhoods is a key part of our work. Religion and the lack of openness in the parent-child relationship inhibit these conversations in Senegal, and so young people don’t tell their parents when they have sexual health problems. We were very present in this area and now we only appear much more rarely in their lives, which has had negative consequences for the health of our young people. If we were still there as before, there would be fewer teenage pregnancies as well, with the advice and contraception that we provide. However, we hand out medication, we care for the community and we educate them when we can, when we are here and we have the money to do so. Our prices remain the same and they are competitive compared with the private clinics and pharmacies in the area. Young people will tell you that they are closer to the midwives and nurses here than to their parents. They can tell them anything. If a girl tells me she has had sex I can give her the morning after pill, but if she goes to the local health center she may feel she is being watched by her neighbours.” Ndeye Yacine Touré is a midwife who regularly fields calls from young women in Guediawaye seeking advice on their sexual health, and who no longer know where to turn. The closure of the Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) clinic in their area has left them seeking often desperate solutions to the taboo of having a child outside of marriage. “Many of our colleagues lost their jobs, and these were people who were supporting their families. It was a loss for the area as a whole, because this is a very poor neighbourhood where people don’t have many options in life. ASBEF Guediawaye was their main source of help because they came here for consultations but also for confidential advice. The services we offer at ASBEF are special, in a way, especially in the area of family planning. Women were at ease at the clinic, but since then there is a gap in their lives. The patients call us day and night wanting advice, asking how to find the main clinic in Dakar. Some say they no longer get check-ups or seek help because they lack the money to go elsewhere. Others say they miss certain midwives or nurses. We make use of emergency funds in several ways. We do pop-up events. I also give them my number and tell them how to get to the clinic in central Dakar, and reassure them that it will all be confidential and that they can seek treatment there. In Senegal, a girl having sex outside marriage isn’t accepted. Some young women were taking contraception secretly, but since the closure of the clinic it’s no longer possible. Some of them got pregnant as a result. They don’t want to bump into their mother at the public clinic so they just stop taking contraception. In Senegal, a girl having sex outside marriage isn’t accepted. The impact on young people is particularly serious. Some tell me they know they have a sexually transmitted infection but they are too afraid to go to the hospital and get it treated. Before they could talk to us and tell us that they had sex, and we could help them. They have to hide now and some seek unsafe abortions. ”

| 16 May 2025

“Since the clinic closed in this town everything has been very difficult"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Betty Guèye is a midwife who used to live in Guediawaye but moved to Dakar after the closure of the clinic in the suburb of Senegal’s capital following global gag rule (GGR) funding cuts. She describes the effects of the closure and how Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) staff try to maximise the reduced service they still offer. “Since the clinic closed in this town everything has been very difficult. The majority of Senegalese are poor and we are losing clients because they cannot access the main clinic in Dakar. If they have an appointment on a Monday, after the weekend they won’t have the 200 francs (35 US cents) needed for the bus, and they will wait until Tuesday or Wednesday to come even though they are in pain. The clinic was of huge benefit to the community of Guediawaye and the surrounding suburbs as well. What we see now is that women wait until pain or infections are at a more advanced stage before they visit us in Dakar. Another effect is that if they need to update their contraception they will exceed the date required for the new injection or pill and then get pregnant as a result. In addition, raising awareness of sexual health in schools and neighbourhoods is a key part of our work. Religion and the lack of openness in the parent-child relationship inhibit these conversations in Senegal, and so young people don’t tell their parents when they have sexual health problems. We were very present in this area and now we only appear much more rarely in their lives, which has had negative consequences for the health of our young people. If we were still there as before, there would be fewer teenage pregnancies as well, with the advice and contraception that we provide. However, we hand out medication, we care for the community and we educate them when we can, when we are here and we have the money to do so. Our prices remain the same and they are competitive compared with the private clinics and pharmacies in the area. Young people will tell you that they are closer to the midwives and nurses here than to their parents. They can tell them anything. If a girl tells me she has had sex I can give her the morning after pill, but if she goes to the local health center she may feel she is being watched by her neighbours.” Ndeye Yacine Touré is a midwife who regularly fields calls from young women in Guediawaye seeking advice on their sexual health, and who no longer know where to turn. The closure of the Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) clinic in their area has left them seeking often desperate solutions to the taboo of having a child outside of marriage. “Many of our colleagues lost their jobs, and these were people who were supporting their families. It was a loss for the area as a whole, because this is a very poor neighbourhood where people don’t have many options in life. ASBEF Guediawaye was their main source of help because they came here for consultations but also for confidential advice. The services we offer at ASBEF are special, in a way, especially in the area of family planning. Women were at ease at the clinic, but since then there is a gap in their lives. The patients call us day and night wanting advice, asking how to find the main clinic in Dakar. Some say they no longer get check-ups or seek help because they lack the money to go elsewhere. Others say they miss certain midwives or nurses. We make use of emergency funds in several ways. We do pop-up events. I also give them my number and tell them how to get to the clinic in central Dakar, and reassure them that it will all be confidential and that they can seek treatment there. In Senegal, a girl having sex outside marriage isn’t accepted. Some young women were taking contraception secretly, but since the closure of the clinic it’s no longer possible. Some of them got pregnant as a result. They don’t want to bump into their mother at the public clinic so they just stop taking contraception. In Senegal, a girl having sex outside marriage isn’t accepted. The impact on young people is particularly serious. Some tell me they know they have a sexually transmitted infection but they are too afraid to go to the hospital and get it treated. Before they could talk to us and tell us that they had sex, and we could help them. They have to hide now and some seek unsafe abortions. ”

| 22 January 2019

“I used to attend the clinic regularly and then one day I didn’t know what happened. The clinic just shut down"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Maguette Mbow, a 33-year-old homemaker, describes how the closure of Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in Guediawaye, a suburb of Dakar, has affected her, and explains the difficulties with the alternative providers available. She spoke about how the closure of her local clinic has impacted her life at a pop-up clinic set up for the day at a school in Guediawaye. “I heard that ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial), was doing consultations here today and I dropped everything at home to come. There was a clinic here in Guediawaye but we don’t have it anymore. I’m here for family planning because that’s what I used to get at the clinic; it was their strong point. I take the Pill and I came to change the type I take, but the midwife advised me today to keep taking the same one. I’ve used the pill between my pregnancies. I have two children aged 2 and 6, but for now I’m not sure if I want a third child. When the clinic closed, I started going to the public facilities instead. There is always an enormous queue. You can get there in the morning and wait until 3pm for a consultation. (The closure) has affected everyone here very seriously. All my friends and family went to ASBEF Guediawaye, but now we are in the other public and private clinics receiving a really poor service. I had all of my pre-natal care at ASBEF and when I was younger I used the services for young people as well. They helped me take the morning after pill a few times and that really left its mark on me. They are great with young people; they are knowledgeable and really good with teenagers. There are still taboos surrounding sexuality in Senegal but they know how to handle them. These days, when ASBEF come to Guediawaye they have to set up in different places each time. It’s a bit annoying because if you know a place well and it’s full of well-trained people who you know personally, you feel more at ease. I would like things to go back to how they were before, and for the clinic to reopen. I would also have liked to send my children there one day when the time came, to benefit from the same service. Sometimes I travel right into Dakar for a consultation at the ASBEF headquarters, but often I don’t have the money.” Fatou Bimtou Diop, 20, is a final year student at Lycée Seydina Limamou Laye in Guediawaye. She explains why the closure of the Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in her area in 2017 means she no longer regularly seeks advice on her sexual health. “I came here today for a consultation. I haven’t been for two years because the clinic closed. I don’t know why that happened but I would really like that decision to be reversed. Yes, there are other clinics here but I don’t feel as relaxed as with ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial). I used to feel really at ease because there were other young people like me there. In the other clinics I know I might see someone’s mother or my aunties and it worries me too much. They explained things well and the set-up felt secure. We could talk about the intimate problems that were affecting us to the ASBEF staff. I went because I have really painful periods, for example. Sometimes I wouldn’t have the nerve to ask certain questions but my friends who went to the ASBEF clinic would ask and then tell me the responses that they got. These days we end up talking a lot about girls who are 14,15 years old who are pregnant. When the ASBEF clinic was there it was really rare to see a girl that young with a baby but now it happens very frequently. A friend’s younger sister has a little boy now and she had to have a caesarian section because she’s younger than us. The clinic in Dakar is too far away. I have to go to school during the day so I can’t take the time off. I came to the session today at school and it was good to discuss my problems, but it took quite a long time to get seen by a midwife.” Ngouye Cissé, a 30-year-old woman who gave birth to her first child in her early teens, but who has since used regular contraception provided by ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial). She visits the association’s pop-up clinics whenever they are in Guediawaye. “I used to attend the clinic regularly and then one day I didn’t know what happened. The clinic just shut down. Senegal’s economic situation is difficult and we don’t have a lot of money. The fees for a consultation are quite expensive, but when ASBEF does come into the community it’s free. I most recently visited the pop-up clinic because I was having some vaginal discharge and I didn’t know why. The midwife took care of me and gave me some advice and medication. Before I came here for my check-up, the public hospital was asking me to do a lot of tests and I was afraid I had some kind of terrible disease. But when I came to the ASBEF midwife simply listened to me, explained what I had, and then gave me the right medication straight away. I feel really relieved. I’m divorced and I have three boys. I had pre-natal care with ASBEF for the first two pregnancies, but with the third, my 2-year-old son, I had to go to a public hospital. The experiences couldn’t be more different. First, there is a big difference in price, as ASBEF is much cheaper. Also, at the ASBEF clinic we are really listened to. The midwife explains things and gives me information. We can talk about our problems openly and without fear, unlike in other health centers. What I see now that the clinic has closed is a lot more pregnant young girls, problems with STIs and in order to get treatment we have to go to the public and private clinics. When people hear that ASBEF is back in town there is a huge rush to get a consultation, because the need is there but people don’t know where else to go. Unfortunately, the transport to go to the clinic in Dakar costs a lot of money for us that we don’t have. Some households don’t even have enough to eat. There isn’t a huge difference between the consultations in the old clinic and the pop-up events that ASBEF organize. They still listen to you properly and it’s well organized. It just takes longer to get seen.” Moudel Bassoum, a 22-year student studying NGO management in Dakar, explains why she has been unable to replace the welcome and care she received at the now closed Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in her hometown of Guediawaye, but still makes us of the pop-up clinic when it is available. “I used to go to the clinic regularly but since it closed, we only see the staff rarely around here. I came with my friends today for a free check-up. I told the whole neighbourhood that ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial) were doing a pop-up clinic today so that they could come for free consultations. It’s not easy to get to the main clinic in Dakar for us. The effects of the closure are numerous, especially on young people. It helped us so much but now I hear a lot more about teenage pregnancies and STIs, not to mention girls trying to abort pregnancies by themselves. When my friend had an infection she went all the way into Dakar for the consultation because the public clinic is more expensive. I would much rather talk to a woman about this type of problem and at the public clinic you don’t get to pick who you talk to. You have to say everything in front of everyone. I don’t think the service we receive since the closure is different when the ASBEF clinic set up here for the day, but the staff are usually not the same and it’s less frequent. It’s free so when they do come there are a lot of people. I would really like the clinic to be re-established when I have a baby one day. I want that welcome, and to know that they will listen to you.”

| 16 May 2025

“I used to attend the clinic regularly and then one day I didn’t know what happened. The clinic just shut down"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Maguette Mbow, a 33-year-old homemaker, describes how the closure of Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in Guediawaye, a suburb of Dakar, has affected her, and explains the difficulties with the alternative providers available. She spoke about how the closure of her local clinic has impacted her life at a pop-up clinic set up for the day at a school in Guediawaye. “I heard that ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial), was doing consultations here today and I dropped everything at home to come. There was a clinic here in Guediawaye but we don’t have it anymore. I’m here for family planning because that’s what I used to get at the clinic; it was their strong point. I take the Pill and I came to change the type I take, but the midwife advised me today to keep taking the same one. I’ve used the pill between my pregnancies. I have two children aged 2 and 6, but for now I’m not sure if I want a third child. When the clinic closed, I started going to the public facilities instead. There is always an enormous queue. You can get there in the morning and wait until 3pm for a consultation. (The closure) has affected everyone here very seriously. All my friends and family went to ASBEF Guediawaye, but now we are in the other public and private clinics receiving a really poor service. I had all of my pre-natal care at ASBEF and when I was younger I used the services for young people as well. They helped me take the morning after pill a few times and that really left its mark on me. They are great with young people; they are knowledgeable and really good with teenagers. There are still taboos surrounding sexuality in Senegal but they know how to handle them. These days, when ASBEF come to Guediawaye they have to set up in different places each time. It’s a bit annoying because if you know a place well and it’s full of well-trained people who you know personally, you feel more at ease. I would like things to go back to how they were before, and for the clinic to reopen. I would also have liked to send my children there one day when the time came, to benefit from the same service. Sometimes I travel right into Dakar for a consultation at the ASBEF headquarters, but often I don’t have the money.” Fatou Bimtou Diop, 20, is a final year student at Lycée Seydina Limamou Laye in Guediawaye. She explains why the closure of the Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in her area in 2017 means she no longer regularly seeks advice on her sexual health. “I came here today for a consultation. I haven’t been for two years because the clinic closed. I don’t know why that happened but I would really like that decision to be reversed. Yes, there are other clinics here but I don’t feel as relaxed as with ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial). I used to feel really at ease because there were other young people like me there. In the other clinics I know I might see someone’s mother or my aunties and it worries me too much. They explained things well and the set-up felt secure. We could talk about the intimate problems that were affecting us to the ASBEF staff. I went because I have really painful periods, for example. Sometimes I wouldn’t have the nerve to ask certain questions but my friends who went to the ASBEF clinic would ask and then tell me the responses that they got. These days we end up talking a lot about girls who are 14,15 years old who are pregnant. When the ASBEF clinic was there it was really rare to see a girl that young with a baby but now it happens very frequently. A friend’s younger sister has a little boy now and she had to have a caesarian section because she’s younger than us. The clinic in Dakar is too far away. I have to go to school during the day so I can’t take the time off. I came to the session today at school and it was good to discuss my problems, but it took quite a long time to get seen by a midwife.” Ngouye Cissé, a 30-year-old woman who gave birth to her first child in her early teens, but who has since used regular contraception provided by ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial). She visits the association’s pop-up clinics whenever they are in Guediawaye. “I used to attend the clinic regularly and then one day I didn’t know what happened. The clinic just shut down. Senegal’s economic situation is difficult and we don’t have a lot of money. The fees for a consultation are quite expensive, but when ASBEF does come into the community it’s free. I most recently visited the pop-up clinic because I was having some vaginal discharge and I didn’t know why. The midwife took care of me and gave me some advice and medication. Before I came here for my check-up, the public hospital was asking me to do a lot of tests and I was afraid I had some kind of terrible disease. But when I came to the ASBEF midwife simply listened to me, explained what I had, and then gave me the right medication straight away. I feel really relieved. I’m divorced and I have three boys. I had pre-natal care with ASBEF for the first two pregnancies, but with the third, my 2-year-old son, I had to go to a public hospital. The experiences couldn’t be more different. First, there is a big difference in price, as ASBEF is much cheaper. Also, at the ASBEF clinic we are really listened to. The midwife explains things and gives me information. We can talk about our problems openly and without fear, unlike in other health centers. What I see now that the clinic has closed is a lot more pregnant young girls, problems with STIs and in order to get treatment we have to go to the public and private clinics. When people hear that ASBEF is back in town there is a huge rush to get a consultation, because the need is there but people don’t know where else to go. Unfortunately, the transport to go to the clinic in Dakar costs a lot of money for us that we don’t have. Some households don’t even have enough to eat. There isn’t a huge difference between the consultations in the old clinic and the pop-up events that ASBEF organize. They still listen to you properly and it’s well organized. It just takes longer to get seen.” Moudel Bassoum, a 22-year student studying NGO management in Dakar, explains why she has been unable to replace the welcome and care she received at the now closed Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in her hometown of Guediawaye, but still makes us of the pop-up clinic when it is available. “I used to go to the clinic regularly but since it closed, we only see the staff rarely around here. I came with my friends today for a free check-up. I told the whole neighbourhood that ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial) were doing a pop-up clinic today so that they could come for free consultations. It’s not easy to get to the main clinic in Dakar for us. The effects of the closure are numerous, especially on young people. It helped us so much but now I hear a lot more about teenage pregnancies and STIs, not to mention girls trying to abort pregnancies by themselves. When my friend had an infection she went all the way into Dakar for the consultation because the public clinic is more expensive. I would much rather talk to a woman about this type of problem and at the public clinic you don’t get to pick who you talk to. You have to say everything in front of everyone. I don’t think the service we receive since the closure is different when the ASBEF clinic set up here for the day, but the staff are usually not the same and it’s less frequent. It’s free so when they do come there are a lot of people. I would really like the clinic to be re-established when I have a baby one day. I want that welcome, and to know that they will listen to you.”

| 22 August 2018

“A radio announcement saved my life” – Gertrude’s story

Gertrude Mugala is a teacher in Fort Portal, a town in Western Uganda. While Gertrude considered herself fairly knowledgeable about cancer, she had never considered taking a screening test or imagined herself ever having the disease. Then one day, she heard an announcement on the radio urging women to go for cervical cancer screenings at a Reproductive Health Uganda (RHU) clinic. “The radio presenter was talking about cervical cancer, and in her message she encouraged all women to get screened. I decided to go and try it out,” she said. Gertrude made her way to RHU's Fort Portal Branch clinic for the free cervical cancer screening. There, she met Ms. Irene Kugonza, an RHU service provider. Ms. Kugonza educated Gertrude and a group of other women about cervical cancer and the importance of routine screening. Gertrude received a type of cervical cancer screening called VIA (visual inspection with acetic acid). "I did not know what was happening" But Gertrude's results were not what she expected; she received a positive result. The good news, however, is that precancerous lesions can be treated if detected early. “I was so shaken when I was told I had pre-cancerous lesions. I did not know what was happening and I didn't believe what I was hearing. I had no idea of my health status. I thought I was healthy, but I was actually harbouring a potential killer disease in me. What would have happened if I didn't go for the screening? If I hadn't heard the radio announcement?” Gertrude was then referred for cryotherapy. “Following cryotherapy, I am now in the process of healing, and I am supposed to go back for review after three months,” said Gertrude. Community screenings Today, Gertrude advocates for cervical cancer screening in her community. She talks to women about cancer, especially cervical cancer, at her workplace, at the market, in meetings, and any other opportunity she gets. “I decided to let women know that cervical cancer is real and it is here with us, and that it kills. At the moment, those are the platforms I have, and I will continue educating women about cancer and encourage them to go for routine testing. I am also happy that I was near my radio that day, where I heard that announcement encouraging all women to get tested for cervical cancer. It might be because of that radio announcement that I am here today,” she said.

| 16 May 2025

“A radio announcement saved my life” – Gertrude’s story

Gertrude Mugala is a teacher in Fort Portal, a town in Western Uganda. While Gertrude considered herself fairly knowledgeable about cancer, she had never considered taking a screening test or imagined herself ever having the disease. Then one day, she heard an announcement on the radio urging women to go for cervical cancer screenings at a Reproductive Health Uganda (RHU) clinic. “The radio presenter was talking about cervical cancer, and in her message she encouraged all women to get screened. I decided to go and try it out,” she said. Gertrude made her way to RHU's Fort Portal Branch clinic for the free cervical cancer screening. There, she met Ms. Irene Kugonza, an RHU service provider. Ms. Kugonza educated Gertrude and a group of other women about cervical cancer and the importance of routine screening. Gertrude received a type of cervical cancer screening called VIA (visual inspection with acetic acid). "I did not know what was happening" But Gertrude's results were not what she expected; she received a positive result. The good news, however, is that precancerous lesions can be treated if detected early. “I was so shaken when I was told I had pre-cancerous lesions. I did not know what was happening and I didn't believe what I was hearing. I had no idea of my health status. I thought I was healthy, but I was actually harbouring a potential killer disease in me. What would have happened if I didn't go for the screening? If I hadn't heard the radio announcement?” Gertrude was then referred for cryotherapy. “Following cryotherapy, I am now in the process of healing, and I am supposed to go back for review after three months,” said Gertrude. Community screenings Today, Gertrude advocates for cervical cancer screening in her community. She talks to women about cancer, especially cervical cancer, at her workplace, at the market, in meetings, and any other opportunity she gets. “I decided to let women know that cervical cancer is real and it is here with us, and that it kills. At the moment, those are the platforms I have, and I will continue educating women about cancer and encourage them to go for routine testing. I am also happy that I was near my radio that day, where I heard that announcement encouraging all women to get tested for cervical cancer. It might be because of that radio announcement that I am here today,” she said.

| 21 May 2017

A graduate in need turns to sex work

The Safe Abortion Action Fund (SAAF) which is hosted by IPPF was set up in 2006 in order to support grass-roots organisations to increase access to safe abortion. One such organisation which received support under the last round of funding is called Lady Mermaid's Bureau. I am Pretty Lynn, aged 25. I am a sex worker but I went to university. I graduated with a Bachelor's Degree in Tourism in 2013. But now, during the day I’m sleeping and during the night I’m working. That is how my day goes every day. I got into sex work through friends. Okay it is not good but I am earning. I tried to get a job when I graduated. I have been applying since I graduated in 2013. I’m still applying but I’m not getting anywhere. You know to get jobs in Uganda; you have to know someone there and no one knows me there. To be a sex worker is like a curse. People look at you like, I don’t know, as someone that has no use in society. People look at you in a bad way. They even don’t consider why you are selling. They just see you as the worst thing that can happen in the society. So it is not comfortable, it is really hard but we try and survive. The fact sex working is illegal means you have to hide yourself when you are selling so that police cannot take you. And then you get diseases, men don’t want to pay. When the police come and take us, sometimes they even use us and don’t pay. So it is really hard. They want a free service. Like if they come and take you and pay that would be fair. But they say it is illegal to sell yourself. But they still use you yet they are saying it is illegal. You can’t report the police because there is no evidence. Abortion and unwanted pregnancies are really common because men don’t want to use condoms and female condoms are really rare and they are expensive. Though at times we get female condoms from Lady Marmaid’s Bureau (LMB) because there are so many of us they can’t keep on giving you them all the time. At times when we get pregnant we use local methods. You can go and use local herbs but it is not safe. One time I used local herbs and I was successful. Then the other time I used Omo washing powder and tea leaves but it was really hard for me. I almost died. I had a friend who died last year from this. But the good thing is that LMB taught us about safe abortion. I have had a safe abortion too. There are some tabs they are called Miso (misoprostol). It costs about fifty thousand shillings (£10 pounds or $20.) It is a lot of money. But if I’m working and I know I’m pregnant, I can say, "this week I’m working for my safe abortion". So if I’m working for twenty thousand, by the end of the week I will have the money. It is expensive compared to Omo at five hundred shillings but that is risky. So if I say I will work this whole week for Miso (misoprostol) it is better. But I'm working and I'm not eating. A project like this one from Lady Mermaid's can help young girls and women. But to take us from sex work, it would really be hard. They would not have enough money to cater for all of us. So what they have to do is to teach us how to protect ourselves, how to defend ourselves. Safe abortion yes. They will just have to sensitise us more about our lives, protection, female condoms and all that. I don't have a boyfriend but maybe when I get money and leave this job I will. But for now, no man would like a woman who sells. No man will bear the wife selling herself. And that will happen only if I get funds, settle somewhere else and become responsible woman. I don’t want this job. I don’t want to be in this business of sex work all the time. I want be married, with my children happily, not selling myself. Stories Read more stories about the amazing success of SAAF in Uganda

| 15 May 2025

A graduate in need turns to sex work

The Safe Abortion Action Fund (SAAF) which is hosted by IPPF was set up in 2006 in order to support grass-roots organisations to increase access to safe abortion. One such organisation which received support under the last round of funding is called Lady Mermaid's Bureau. I am Pretty Lynn, aged 25. I am a sex worker but I went to university. I graduated with a Bachelor's Degree in Tourism in 2013. But now, during the day I’m sleeping and during the night I’m working. That is how my day goes every day. I got into sex work through friends. Okay it is not good but I am earning. I tried to get a job when I graduated. I have been applying since I graduated in 2013. I’m still applying but I’m not getting anywhere. You know to get jobs in Uganda; you have to know someone there and no one knows me there. To be a sex worker is like a curse. People look at you like, I don’t know, as someone that has no use in society. People look at you in a bad way. They even don’t consider why you are selling. They just see you as the worst thing that can happen in the society. So it is not comfortable, it is really hard but we try and survive. The fact sex working is illegal means you have to hide yourself when you are selling so that police cannot take you. And then you get diseases, men don’t want to pay. When the police come and take us, sometimes they even use us and don’t pay. So it is really hard. They want a free service. Like if they come and take you and pay that would be fair. But they say it is illegal to sell yourself. But they still use you yet they are saying it is illegal. You can’t report the police because there is no evidence. Abortion and unwanted pregnancies are really common because men don’t want to use condoms and female condoms are really rare and they are expensive. Though at times we get female condoms from Lady Marmaid’s Bureau (LMB) because there are so many of us they can’t keep on giving you them all the time. At times when we get pregnant we use local methods. You can go and use local herbs but it is not safe. One time I used local herbs and I was successful. Then the other time I used Omo washing powder and tea leaves but it was really hard for me. I almost died. I had a friend who died last year from this. But the good thing is that LMB taught us about safe abortion. I have had a safe abortion too. There are some tabs they are called Miso (misoprostol). It costs about fifty thousand shillings (£10 pounds or $20.) It is a lot of money. But if I’m working and I know I’m pregnant, I can say, "this week I’m working for my safe abortion". So if I’m working for twenty thousand, by the end of the week I will have the money. It is expensive compared to Omo at five hundred shillings but that is risky. So if I say I will work this whole week for Miso (misoprostol) it is better. But I'm working and I'm not eating. A project like this one from Lady Mermaid's can help young girls and women. But to take us from sex work, it would really be hard. They would not have enough money to cater for all of us. So what they have to do is to teach us how to protect ourselves, how to defend ourselves. Safe abortion yes. They will just have to sensitise us more about our lives, protection, female condoms and all that. I don't have a boyfriend but maybe when I get money and leave this job I will. But for now, no man would like a woman who sells. No man will bear the wife selling herself. And that will happen only if I get funds, settle somewhere else and become responsible woman. I don’t want this job. I don’t want to be in this business of sex work all the time. I want be married, with my children happily, not selling myself. Stories Read more stories about the amazing success of SAAF in Uganda

| 20 May 2017

Working to stop unsafe abortion for school girls

The Safe Abortion Action Fund (SAAF) which is hosted by IPPF was set up in 2006 in order to support grass-roots organisations to increase access to safe abortion. One such organisation which received support under the last round of funding is called Volunteers for Development Association Uganda (VODA). Unsafe abortion is a huge problem in Uganda with an estimated 400,000 women having an unsafe abortion per year. The law is confusing and unclear, with abortion permitted only under certain circumstances. Post-abortion care is permitted to treat women who have undergone an unsafe abortion, however lack of awareness of the law and stigma surrounding abortion mean that service providers are not always willing to treat patients who arrive seeking care. The VODA project aims to ensure that young women in Uganda are able to lead healthier lives free from unsafe abortion related deaths or complications through reducing abortion stigma in the community, increasing access to abortion-related services and ensuring the providers are trained to provide quality post-abortion care services. I am Helen. I have been a midwife at this small clinic for seven years and I have worked with VODA for four years. Unsafe abortion continues and some schoolgirls are raped. They then go to local herbalists and some of them tell me that they are given emilandira [roots] which they insert inside themselves to rupture the membranes. Some of them even try to induce an abortion by using Omo [douching with detergent or bleach]. At the end of the day they get complications then they land here, so we help them. Unsafe abortion is very common. In one month you can get more than five cases. It is a big problem. We help them, they need to go back to school, and we counsel them. If it is less than 12 weeks, we handle them from here. If they are more than 12 weeks along we refer them to the hospital. Most referrals from VODA are related to unwanted pregnancies, HIV testing, family planning, and youth friendly services. A few parents come for services for their children who are at school. So we counsel them that contraception, other than condoms, will only prevent pregnancy, but you can still get HIV and STIs, so take care. I am Josephine and I work as a midwife at a rural health centre. I deal with pregnant mothers, postnatal mothers, and there are girls who come with problems like unwanted pregnancy. I used to have a negative attitude towards abortion. But then VODA helped us understand the importance of helping someone with the problem because many people were dying in the villages because of unsafe abortion. According to my religion, helping someone to have an abortion was not allowed. But again when you look into it, it’s not good to leave someone to die. So I decided to change my attitude to help people. Post-abortion care has helped many people because these days we don’t have many people in the villages dying because of unsafe abortion. These days I’m proud of what we are doing because before I didn’t know the importance of helping someone with a problem. But these days, since people no longer die, people no longer get problems and I’m proud and happy because we help so many people. My name is Jonathan. I am married with three children. I have a Bachelor of Social Work and Social Administration. I have worked with VODA as a project officer since 2008. Due to the training that we have done about abortion many people have changed their attitudes and we have helped people to talk about the issue. Most people were against abortion before but they are now realising that if it’s done safely it is important because otherwise many people die from unsafe abortion. I have talked to religious leaders, I have talked to local leaders; I have talked to people of different categories. At first when you approach them, they have a different perception. The health workers were difficult to work with at first. However they knew people were approaching them with the problems of unsafe abortion. Due to religion, communities can be hard against this issue. But after some time we have seen that they have changed their perception toward the issue of safe and unsafe abortion. And now many of them know that in some instances, abortion is inevitable but it should be done in a safe way. I’m Stevens and I am nurse. We have some clients who come when they have already attempted an unsafe abortion. You find that it is often inevitable. The only solution you have to help those clients is to provide treatment of incomplete abortion as part of post-abortion care. Because of the VODA project there is a very remarkable change in the community. Now, those people who used to have unsafe abortions locally, know where to go for post-abortion care - unlike in the past. I remember a schoolgirl, she was in a very sorry state because she had tried some local remedies to abort. I attended to her and things went well. She went back to school. I feel so proud because that was a big life rescue. A girl like that could have died but now she is alive and I see her carrying on with her studies, I feel so proud. I praise VODA for that encouragement. This service should be legalised because whether they restrict it or not, there is abortion and it is going on. And if it’s not out in the open, so that our people know where to go for such services, it leads to more deaths. Stories Read more stories about the amazing success of SAAF in Uganda

| 16 May 2025

Working to stop unsafe abortion for school girls

The Safe Abortion Action Fund (SAAF) which is hosted by IPPF was set up in 2006 in order to support grass-roots organisations to increase access to safe abortion. One such organisation which received support under the last round of funding is called Volunteers for Development Association Uganda (VODA). Unsafe abortion is a huge problem in Uganda with an estimated 400,000 women having an unsafe abortion per year. The law is confusing and unclear, with abortion permitted only under certain circumstances. Post-abortion care is permitted to treat women who have undergone an unsafe abortion, however lack of awareness of the law and stigma surrounding abortion mean that service providers are not always willing to treat patients who arrive seeking care. The VODA project aims to ensure that young women in Uganda are able to lead healthier lives free from unsafe abortion related deaths or complications through reducing abortion stigma in the community, increasing access to abortion-related services and ensuring the providers are trained to provide quality post-abortion care services. I am Helen. I have been a midwife at this small clinic for seven years and I have worked with VODA for four years. Unsafe abortion continues and some schoolgirls are raped. They then go to local herbalists and some of them tell me that they are given emilandira [roots] which they insert inside themselves to rupture the membranes. Some of them even try to induce an abortion by using Omo [douching with detergent or bleach]. At the end of the day they get complications then they land here, so we help them. Unsafe abortion is very common. In one month you can get more than five cases. It is a big problem. We help them, they need to go back to school, and we counsel them. If it is less than 12 weeks, we handle them from here. If they are more than 12 weeks along we refer them to the hospital. Most referrals from VODA are related to unwanted pregnancies, HIV testing, family planning, and youth friendly services. A few parents come for services for their children who are at school. So we counsel them that contraception, other than condoms, will only prevent pregnancy, but you can still get HIV and STIs, so take care. I am Josephine and I work as a midwife at a rural health centre. I deal with pregnant mothers, postnatal mothers, and there are girls who come with problems like unwanted pregnancy. I used to have a negative attitude towards abortion. But then VODA helped us understand the importance of helping someone with the problem because many people were dying in the villages because of unsafe abortion. According to my religion, helping someone to have an abortion was not allowed. But again when you look into it, it’s not good to leave someone to die. So I decided to change my attitude to help people. Post-abortion care has helped many people because these days we don’t have many people in the villages dying because of unsafe abortion. These days I’m proud of what we are doing because before I didn’t know the importance of helping someone with a problem. But these days, since people no longer die, people no longer get problems and I’m proud and happy because we help so many people. My name is Jonathan. I am married with three children. I have a Bachelor of Social Work and Social Administration. I have worked with VODA as a project officer since 2008. Due to the training that we have done about abortion many people have changed their attitudes and we have helped people to talk about the issue. Most people were against abortion before but they are now realising that if it’s done safely it is important because otherwise many people die from unsafe abortion. I have talked to religious leaders, I have talked to local leaders; I have talked to people of different categories. At first when you approach them, they have a different perception. The health workers were difficult to work with at first. However they knew people were approaching them with the problems of unsafe abortion. Due to religion, communities can be hard against this issue. But after some time we have seen that they have changed their perception toward the issue of safe and unsafe abortion. And now many of them know that in some instances, abortion is inevitable but it should be done in a safe way. I’m Stevens and I am nurse. We have some clients who come when they have already attempted an unsafe abortion. You find that it is often inevitable. The only solution you have to help those clients is to provide treatment of incomplete abortion as part of post-abortion care. Because of the VODA project there is a very remarkable change in the community. Now, those people who used to have unsafe abortions locally, know where to go for post-abortion care - unlike in the past. I remember a schoolgirl, she was in a very sorry state because she had tried some local remedies to abort. I attended to her and things went well. She went back to school. I feel so proud because that was a big life rescue. A girl like that could have died but now she is alive and I see her carrying on with her studies, I feel so proud. I praise VODA for that encouragement. This service should be legalised because whether they restrict it or not, there is abortion and it is going on. And if it’s not out in the open, so that our people know where to go for such services, it leads to more deaths. Stories Read more stories about the amazing success of SAAF in Uganda

| 20 May 2017

A mother's heart break after losing teen daughter to unsafe abortion

The Safe Abortion Action Fund (SAAF) which is hosted by IPPF was set up in 2006 in order to support grass-roots organisations to increase access to safe abortion. One such organisation which received support under the last round of funding is called Volunteers for Development Association Uganda (VODA). Margaret's daughter, Gladys, was raped by a relative as a teenager and became pregnant. She did not tell her mother what had happened and not wanting to have a child at such a young age conceived through incest, Gladys tried to terminate the pregnancy herself using local herbs but got an infection and died. "My name is Margaret and I am a widow." "I lost my daughter in 2011. She was called Gladys and she was 16. I didn’t know that she was pregnant. She tried to use local herbs to abort. I only found out about it three days later when she was bleeding very heavily. I tried to take her to the hospital but unfortunately she died on the way." Despite being the cause of many deaths in the region, the stigma surrounding abortion means that most people do not mention the cause of death publically. However at Gladys' funeral one of her school friends spoke out and said that she had died due to unsafe abortion. This prompted VODA to start working on the issue and when the project started they included Margaret in their training on how to prevent unsafe abortion. "The training made me stronger to talk about it. Now, I continue to tell my remaining two girls about the dangers of unsafe abortion, sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies. VODA has really helped us. I think my girl wouldn’t have died if VODA was active then like it is now." "I have used VODA's information to carry on with my parental work. That information has been helpful because we are noticing change. I keep on reminding them, 'didn’t you see what happened to your friend here?'. So they have really changed especially with the ongoing help of the people from VODA." "Unsafe abortion was rampant in the past. We had tried to speak to the students, as parents, but it seemed that our information was not enough. But now we have another helping hand from VODA, especially with those seminars targeting the girls." Stories Read more stories about the amazing success of SAAF in Uganda

| 16 May 2025

A mother's heart break after losing teen daughter to unsafe abortion

The Safe Abortion Action Fund (SAAF) which is hosted by IPPF was set up in 2006 in order to support grass-roots organisations to increase access to safe abortion. One such organisation which received support under the last round of funding is called Volunteers for Development Association Uganda (VODA). Margaret's daughter, Gladys, was raped by a relative as a teenager and became pregnant. She did not tell her mother what had happened and not wanting to have a child at such a young age conceived through incest, Gladys tried to terminate the pregnancy herself using local herbs but got an infection and died. "My name is Margaret and I am a widow." "I lost my daughter in 2011. She was called Gladys and she was 16. I didn’t know that she was pregnant. She tried to use local herbs to abort. I only found out about it three days later when she was bleeding very heavily. I tried to take her to the hospital but unfortunately she died on the way." Despite being the cause of many deaths in the region, the stigma surrounding abortion means that most people do not mention the cause of death publically. However at Gladys' funeral one of her school friends spoke out and said that she had died due to unsafe abortion. This prompted VODA to start working on the issue and when the project started they included Margaret in their training on how to prevent unsafe abortion. "The training made me stronger to talk about it. Now, I continue to tell my remaining two girls about the dangers of unsafe abortion, sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies. VODA has really helped us. I think my girl wouldn’t have died if VODA was active then like it is now." "I have used VODA's information to carry on with my parental work. That information has been helpful because we are noticing change. I keep on reminding them, 'didn’t you see what happened to your friend here?'. So they have really changed especially with the ongoing help of the people from VODA." "Unsafe abortion was rampant in the past. We had tried to speak to the students, as parents, but it seemed that our information was not enough. But now we have another helping hand from VODA, especially with those seminars targeting the girls." Stories Read more stories about the amazing success of SAAF in Uganda

| 20 May 2017

Educating their peers about unsafe abortion

The Safe Abortion Action Fund (SAAF) which is hosted by IPPF was set up in 2006 in order to support grassroots organisations to increase access to safe abortion. One such organisation which received support under the last round of funding is called Volunteers for Development Association Uganda (VODA). Peer educators in schools provide counselling and advice to other students, who otherwise would have no one to turn to in times of crisis. Today, we have the largest generation of young people ever, each one with their own unique needs. Peer educators are critical in gaining the trust and confidence of hundreds of young girls each term, and together they help each other gain more knowledge about their sexual and reproductive health. Peer educators themselves also gain a great deal from the training and experience and VODA has been successful in empowering many of these young girls to feel confident and be able to talk out in public, something that they were not able to do before. Poverty, gender inequality, lack of knowledge about sex and relationships and lack of access to sanitary protection mean that girls in rural Uganda are at high risk of sexual exploitation and abuse. All of this coupled with very little access to contraception means that Uganda has high rates of unintended pregnancies among young girls. Despite abortion being legal in Uganda in cases of rape and incest, most girls are not aware of the law and resort to unsafe abortion often using local herbs or washing liquid. The peer educators trained by VODA are able to listen to other young people's issues and provide support and information a range of issues including safe abortion as well as how to access contraception. My name is Mabel. I am in my final year of O'Levels and I am a peer counsellor at a Secondary School in Namuganga. I was selected with two others by VODA and my head teacher, and then trained to be a peer counsellor. We were trained to help our colleagues at school to handle various problems. Girls used to get pregnant and some were dropping out of school. So we counselled many of our colleagues about unwanted pregnancies. We have seen a change because we get free condoms from VODA. We could preach abstinence from sex. For those that could not manage abstinence, we could give them male condoms. Unsafe abortion has been a big problem. Girls were using local herbs and sharp instruments like metallic hangers for abortion. Many would get injured and some would die. I remember last year there was a girl who aborted using those local methods but she died and was buried in Seeta. If VODA wasn't here I think things would be very bad because as students, we did not have access to most of the information that we needed. We would have seen a big number of girls out of school because of unwanted pregnancies or unsafe abortion. I have benefited a lot. I have acquired information which I have used to keep myself safe in terms of unwanted pregnancies. I don’t think I could ever be lured to perform unsafe abortion because I know the risks. In the past, I wasn't able to speak in public but now I can stand and talk freely. I’m Sharon and I’m a student counsellor at a Secondary School in Namuganga. I counsel fellow students, young people in communities and even adults. Before I was selected for VODA training I thought it was just an organisation to promote abortion. But then I realised they were addressing a big problem that was happening at our school and our villages. I have learnt that when someone gets pregnant I don’t have to force her to abort and I don’t encourage her to go for unsafe abortion. If we hear that a certain girl has a boyfriend, we approach her and counsel her on issues like unwanted pregnancy. Many young girls have been lured into early sex because they need money, which is why we end up with unwanted pregnancies. In a bid to fulfil those needs, they get boyfriends or other guys who use them for money, impregnate them and then leave. The girls know about contraceptives like the pill and we have given some of them referral cards for them to access the contraceptives from the health centres. But there has been debate against giving young girls contraceptives. There are restrictions that the government puts in place but that does not mean that girls are not getting pregnant. I remember the girls who died after aborting through unsafe abortion methods and I think about the lives that would have been saved if they had knowledge about contraceptives. I’m Rita and I’m 15-years-old. I was twelve when I was selected to be a VODA counsellor in my primary school. I was lucky because many people wanted to be counsellors but I was chosen. My parents were very happy and they got interested. When I joined this school, I introduced myself to other students because I wanted to continue with my work as a counsellor. I told my colleagues to feel free to share with me their issues. We are lucky here because there are many counsellors. Girls are having unwanted pregnancies because they are lured by men who give them presents and things such as money for sanitary pads that they cannot get from their parents. Before I joined this school, there were many cases of girls terminating pregnancies with unsafe abortions. It was common to hear of or see someone who had aborted. Many would abort so that they would return to school. When I joined this school last year and we intensified the counselling sessions, many came and shared their problems with us. We have learnt that two girls at school gave birth and have since returned to school but we have not had cases of unsafe abortions here since I joined. I wasn’t as serious with studies before I became a counsellor but because I want to maintain my status, I have improved in my studies because I don’t want to feel ashamed in front of my fellow students. VODA gave us T-shirts for identification purposes which has made people in the community respect me as well. In terms of preventing unwanted pregnancies in schools, most of what we see here originates from the girls' homes. Many parents don’t provide for the girls’ necessities (like sanitary towels) so that makes them vulnerable to be lured by men. Stories Read more stories about the amazing success of SAAF in Uganda

| 16 May 2025

Educating their peers about unsafe abortion

The Safe Abortion Action Fund (SAAF) which is hosted by IPPF was set up in 2006 in order to support grassroots organisations to increase access to safe abortion. One such organisation which received support under the last round of funding is called Volunteers for Development Association Uganda (VODA). Peer educators in schools provide counselling and advice to other students, who otherwise would have no one to turn to in times of crisis. Today, we have the largest generation of young people ever, each one with their own unique needs. Peer educators are critical in gaining the trust and confidence of hundreds of young girls each term, and together they help each other gain more knowledge about their sexual and reproductive health. Peer educators themselves also gain a great deal from the training and experience and VODA has been successful in empowering many of these young girls to feel confident and be able to talk out in public, something that they were not able to do before. Poverty, gender inequality, lack of knowledge about sex and relationships and lack of access to sanitary protection mean that girls in rural Uganda are at high risk of sexual exploitation and abuse. All of this coupled with very little access to contraception means that Uganda has high rates of unintended pregnancies among young girls. Despite abortion being legal in Uganda in cases of rape and incest, most girls are not aware of the law and resort to unsafe abortion often using local herbs or washing liquid. The peer educators trained by VODA are able to listen to other young people's issues and provide support and information a range of issues including safe abortion as well as how to access contraception. My name is Mabel. I am in my final year of O'Levels and I am a peer counsellor at a Secondary School in Namuganga. I was selected with two others by VODA and my head teacher, and then trained to be a peer counsellor. We were trained to help our colleagues at school to handle various problems. Girls used to get pregnant and some were dropping out of school. So we counselled many of our colleagues about unwanted pregnancies. We have seen a change because we get free condoms from VODA. We could preach abstinence from sex. For those that could not manage abstinence, we could give them male condoms. Unsafe abortion has been a big problem. Girls were using local herbs and sharp instruments like metallic hangers for abortion. Many would get injured and some would die. I remember last year there was a girl who aborted using those local methods but she died and was buried in Seeta. If VODA wasn't here I think things would be very bad because as students, we did not have access to most of the information that we needed. We would have seen a big number of girls out of school because of unwanted pregnancies or unsafe abortion. I have benefited a lot. I have acquired information which I have used to keep myself safe in terms of unwanted pregnancies. I don’t think I could ever be lured to perform unsafe abortion because I know the risks. In the past, I wasn't able to speak in public but now I can stand and talk freely. I’m Sharon and I’m a student counsellor at a Secondary School in Namuganga. I counsel fellow students, young people in communities and even adults. Before I was selected for VODA training I thought it was just an organisation to promote abortion. But then I realised they were addressing a big problem that was happening at our school and our villages. I have learnt that when someone gets pregnant I don’t have to force her to abort and I don’t encourage her to go for unsafe abortion. If we hear that a certain girl has a boyfriend, we approach her and counsel her on issues like unwanted pregnancy. Many young girls have been lured into early sex because they need money, which is why we end up with unwanted pregnancies. In a bid to fulfil those needs, they get boyfriends or other guys who use them for money, impregnate them and then leave. The girls know about contraceptives like the pill and we have given some of them referral cards for them to access the contraceptives from the health centres. But there has been debate against giving young girls contraceptives. There are restrictions that the government puts in place but that does not mean that girls are not getting pregnant. I remember the girls who died after aborting through unsafe abortion methods and I think about the lives that would have been saved if they had knowledge about contraceptives. I’m Rita and I’m 15-years-old. I was twelve when I was selected to be a VODA counsellor in my primary school. I was lucky because many people wanted to be counsellors but I was chosen. My parents were very happy and they got interested. When I joined this school, I introduced myself to other students because I wanted to continue with my work as a counsellor. I told my colleagues to feel free to share with me their issues. We are lucky here because there are many counsellors. Girls are having unwanted pregnancies because they are lured by men who give them presents and things such as money for sanitary pads that they cannot get from their parents. Before I joined this school, there were many cases of girls terminating pregnancies with unsafe abortions. It was common to hear of or see someone who had aborted. Many would abort so that they would return to school. When I joined this school last year and we intensified the counselling sessions, many came and shared their problems with us. We have learnt that two girls at school gave birth and have since returned to school but we have not had cases of unsafe abortions here since I joined. I wasn’t as serious with studies before I became a counsellor but because I want to maintain my status, I have improved in my studies because I don’t want to feel ashamed in front of my fellow students. VODA gave us T-shirts for identification purposes which has made people in the community respect me as well. In terms of preventing unwanted pregnancies in schools, most of what we see here originates from the girls' homes. Many parents don’t provide for the girls’ necessities (like sanitary towels) so that makes them vulnerable to be lured by men. Stories Read more stories about the amazing success of SAAF in Uganda

| 20 May 2017

Post-abortion care for straight-A student