Spotlight

A selection of stories from across the Federation

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in the face of growing opposition and the rise of the far right? These victories for sexual and reproductive rights and health are the result of relentless grassroots work and advocacy by our Member Associations, in partnership with community organizations, allied politicians, and the mobilization of public opinion.

Most Popular This Week

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in t

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan's Rising HIV Crisis: A Call for Action

On World AIDS Day, we commemorate the remarkable achievements of IPPF Member Associations in their unwavering commitment to combating the HIV epidemic.

Ensuring SRHR in Humanitarian Crises: What You Need to Know

Over the past two decades, global forced displacement has consistently increased, affecting an estimated 114 million people as of mid-2023.

Estonia, Nepal, Namibia, Japan, Thailand

The Rainbow Wave for Marriage Equality

Love wins! The fight for marriage equality has seen incredible progress worldwide, with a recent surge in legalizations.

France, Germany, Poland, United Kingdom, United States, Colombia, India, Tunisia

Abortion Rights: Latest Decisions and Developments around the World

Over the past 30 years, more than

Palestine

In their own words: The people providing sexual and reproductive health care under bombardment in Gaza

Week after week, heavy Israeli bombardment from air, land, and sea, has continued across most of the Gaza Strip.

Vanuatu

When getting to the hospital is difficult, Vanuatu mobile outreach can save lives

In the mountains of Kumera on Tanna Island, Vanuatu, the village women of Kamahaul normally spend over 10,000 Vatu ($83 USD) to travel to the nearest hospital.

Filter our stories by:

- Afghanistan

- Albania

- Aruba

- Bangladesh

- Benin

- Botswana

- Burundi

- Cambodia

- Cameroon

- Colombia

- Congo, Dem. Rep.

- Cook Islands

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Ethiopia

- Fiji

- France

- Germany

- Ghana

- Guinea-Conakry

- India

- Ireland

- (-) Jamaica

- Japan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kiribati

- Lesotho

- Malawi

- Mali

- Mozambique

- Namibia

- Nepal

- Nigeria

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Poland

- (-) Senegal

- Somaliland

- Sri Lanka

- Sudan

- Thailand

- Togo

- Tonga

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Tunisia

- Uganda

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Vanuatu

- Zambia

| 11 March 2021

“There’s a lot going through these teenagers’ minds”

Fiona, 28, joined the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN) Lenworth Jacobs Clinic in 2017 as a volunteer through a one-year internship with the Jamaica Social Investment Fund. “I was placed to be a youth officer, which I never had any knowledge of. Upon getting the role I knew there would be challenges. I was not happy. I wanted a place in the food and beverage industry. I thought to myself, ‘what am I doing here? This has nothing to do with my qualifications’. It was baby mother business at clinic, and I can’t manage the drama,” Fiona says. Embracing an unexpected opportunity Fiona’s perception of FAMPLAN quickly changed when she was introduced to its Youth Advocacy Movement (YAM) and began recruiting members from her own community to join. “I quickly learnt new skills such as social media marketing, logistics skills and administrative skills. In fact, the only thing I can’t do is administer the vaccines. They have provided me with a lot of training here. Right now, I have a Provider Initiative Training and Counselling certificate. I am an HIV tester and counsellor. I volunteer at health fairs and special functions. I will leave here better than I came.” Working with vulnerable communities The Lenworth Jacobs Clinic is located in tough neighbourhood in Downtown, Kingston. Fiona says there is vital work to be done, and youth are the vanguards for change. “It’s a volatile area so some clients you have to take a deep breath to deal with them as humans. I am no stranger to the ghetto. I grew up there. The young people will come, and they’ll talk openly about sex. They’ll mention multiple partners. You have to tell them choose two [barrier and hormonal contraception] to be safe, you encourage them to protect themselves,” she says. Other challenges that young people face include sexual grooming, teenage pregnancy, and violation of their sexual rights. “Sometimes men may lurk after them. There is sexual grooming where men feel entitled to their bodies. A lot are just having sex. They don’t know the consequences or the sickness and potential diseases that can come as a result of unprotected sex. Many don’t know there are options - contraceptives. Some don’t know the dangers of multiple sex partners. The challenges are their lifestyle, poverty level, environment, and sex is often transactional to deal with economic struggles,” Fiona explains. Providing a safe space to young communities Despite these challenges YAM has provided a safe space for many young people to discuss issues like sexual consent, sexual health and rights, sexuality and provide them with accurate information access to FAMPLAN’s healthcare. But there remains a need for more youth volunteers, and adults, to support FAMPLAN’s work. “We need more young people, and we definitely need an adult group. Teens can carry the message, but you’re likely to hear parents say, ‘I’ve been through it already’ and not listen. They also need the education YAMs have access to, so they can deal with their children, grandchildren and educate them about sexual and reproductive health rights. For my first community intervention a lot of kids came out and had questions to ask. Questions that needed answers. I had to get my colleagues to come and answer,” Fiona says. YAM’s impact goes beyond sexual and reproductive health, as the group has supported many young people on issues of self-harm and depression. “There’s a lot going through these teenagers’ minds. Through YAM I have developed relationships and become their confidante, so they can call me for anything. The movement is impacting. It helped me with my life and now I can pass it down. YAM can go a far way with the right persons. Whatever we do we do it with fun and education – edutainment.”

| 11 March 2021

“There’s a lot going through these teenagers’ minds”

Fiona, 28, joined the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN) Lenworth Jacobs Clinic in 2017 as a volunteer through a one-year internship with the Jamaica Social Investment Fund. “I was placed to be a youth officer, which I never had any knowledge of. Upon getting the role I knew there would be challenges. I was not happy. I wanted a place in the food and beverage industry. I thought to myself, ‘what am I doing here? This has nothing to do with my qualifications’. It was baby mother business at clinic, and I can’t manage the drama,” Fiona says. Embracing an unexpected opportunity Fiona’s perception of FAMPLAN quickly changed when she was introduced to its Youth Advocacy Movement (YAM) and began recruiting members from her own community to join. “I quickly learnt new skills such as social media marketing, logistics skills and administrative skills. In fact, the only thing I can’t do is administer the vaccines. They have provided me with a lot of training here. Right now, I have a Provider Initiative Training and Counselling certificate. I am an HIV tester and counsellor. I volunteer at health fairs and special functions. I will leave here better than I came.” Working with vulnerable communities The Lenworth Jacobs Clinic is located in tough neighbourhood in Downtown, Kingston. Fiona says there is vital work to be done, and youth are the vanguards for change. “It’s a volatile area so some clients you have to take a deep breath to deal with them as humans. I am no stranger to the ghetto. I grew up there. The young people will come, and they’ll talk openly about sex. They’ll mention multiple partners. You have to tell them choose two [barrier and hormonal contraception] to be safe, you encourage them to protect themselves,” she says. Other challenges that young people face include sexual grooming, teenage pregnancy, and violation of their sexual rights. “Sometimes men may lurk after them. There is sexual grooming where men feel entitled to their bodies. A lot are just having sex. They don’t know the consequences or the sickness and potential diseases that can come as a result of unprotected sex. Many don’t know there are options - contraceptives. Some don’t know the dangers of multiple sex partners. The challenges are their lifestyle, poverty level, environment, and sex is often transactional to deal with economic struggles,” Fiona explains. Providing a safe space to young communities Despite these challenges YAM has provided a safe space for many young people to discuss issues like sexual consent, sexual health and rights, sexuality and provide them with accurate information access to FAMPLAN’s healthcare. But there remains a need for more youth volunteers, and adults, to support FAMPLAN’s work. “We need more young people, and we definitely need an adult group. Teens can carry the message, but you’re likely to hear parents say, ‘I’ve been through it already’ and not listen. They also need the education YAMs have access to, so they can deal with their children, grandchildren and educate them about sexual and reproductive health rights. For my first community intervention a lot of kids came out and had questions to ask. Questions that needed answers. I had to get my colleagues to come and answer,” Fiona says. YAM’s impact goes beyond sexual and reproductive health, as the group has supported many young people on issues of self-harm and depression. “There’s a lot going through these teenagers’ minds. Through YAM I have developed relationships and become their confidante, so they can call me for anything. The movement is impacting. It helped me with my life and now I can pass it down. YAM can go a far way with the right persons. Whatever we do we do it with fun and education – edutainment.”

| 11 March 2021

“It’s so much more than sex and condoms”

‘Are you interested in advocacy and reproductive health rights?’ These were the words which caught Mario’s attention and prompted him to sign up to be part of the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN) Youth Advocacy Movement (YAM) five years ago. At the time, Mario was 22 and looking for opportunities to gain experience after graduating from college. From graduate to advocate “I was on Facebook looking at different things young people can do, and it popped up. I had just left college with an Associate Degree in Hospitality and Tourism Management. I was unemployed and I just wanted to be active, give myself the opportunity to learn and find something I can give my time to and gain from it,” Mario says. Interested in volunteering and advocacy Mario joined the YAM to get a new experience and broaden his knowledge base. He says he has gained a second family and a safe space; he can call home. “It’s so much more than sex and condoms. It’s really human rights and integrated in everything we do. Reproductive health affects the population, it affects your income, your family planning, how people have access to rights. It’s cuts across men, women, LGBT people and encompasses everything. My love for working with YAM and being an advocate for sexual and reproductive health rights deepened and I could expand further in my outreach.” His work with YAM has equipped Mario with skills and given him opportunities he would otherwise not have. “I have done public speaking which has opened lots of doors for me. I have travelled and met with other Caribbean people about issues [around sexual and reproductive health]. There’s an appreciation for diversity as you deal with lots of people when you go out into communities, so you learn to break down walls and you learn how to communicate with different people.” Challenging the reluctance to talk about sex The greatest challenges he faces are people’s reluctance to talk about sex, accessing healthcare, and misinformation. “Once they hear sex it’s kind of a behind the door situation with everybody, but they are interested in getting condoms. When it comes to that it is breaking taboo in people’s minds and it might not be something people readily accept at the time. LGBT rights, access to condoms and access to reproductive health for young people at a certain age — many people don’t appreciate those things in Jamaica.” Mario talks about giving youth individual rights to access healthcare. “So, can they go to a doctor, nurse without worrying if they are old enough or if the doctor or nurse will talk back to the parents? Access is about giving them the knowledge and empowering them to go for what they need.” “The stigma is the misinformation. If you’re going to the clinic people automatically assume, you’re doing an HIV/AIDS test or getting an abortion. [So] after the community empowerment, because of the stigma maybe 15 per cent will respond and come to the clinic. The biggest issue is misinformation,” Mario says, adding that diversification of the content and how messages are shaped could possibly help. To address these issues, he wants to see more young people involved in advocacy and helping to push FAMPLAN’s messages in a diversified way. “It is a satisfying thing to do both for your own self development and community development. You’re building a network. If you put yourself out there you don’t know what can happen.”

| 10 February 2021

“It’s so much more than sex and condoms”

‘Are you interested in advocacy and reproductive health rights?’ These were the words which caught Mario’s attention and prompted him to sign up to be part of the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN) Youth Advocacy Movement (YAM) five years ago. At the time, Mario was 22 and looking for opportunities to gain experience after graduating from college. From graduate to advocate “I was on Facebook looking at different things young people can do, and it popped up. I had just left college with an Associate Degree in Hospitality and Tourism Management. I was unemployed and I just wanted to be active, give myself the opportunity to learn and find something I can give my time to and gain from it,” Mario says. Interested in volunteering and advocacy Mario joined the YAM to get a new experience and broaden his knowledge base. He says he has gained a second family and a safe space; he can call home. “It’s so much more than sex and condoms. It’s really human rights and integrated in everything we do. Reproductive health affects the population, it affects your income, your family planning, how people have access to rights. It’s cuts across men, women, LGBT people and encompasses everything. My love for working with YAM and being an advocate for sexual and reproductive health rights deepened and I could expand further in my outreach.” His work with YAM has equipped Mario with skills and given him opportunities he would otherwise not have. “I have done public speaking which has opened lots of doors for me. I have travelled and met with other Caribbean people about issues [around sexual and reproductive health]. There’s an appreciation for diversity as you deal with lots of people when you go out into communities, so you learn to break down walls and you learn how to communicate with different people.” Challenging the reluctance to talk about sex The greatest challenges he faces are people’s reluctance to talk about sex, accessing healthcare, and misinformation. “Once they hear sex it’s kind of a behind the door situation with everybody, but they are interested in getting condoms. When it comes to that it is breaking taboo in people’s minds and it might not be something people readily accept at the time. LGBT rights, access to condoms and access to reproductive health for young people at a certain age — many people don’t appreciate those things in Jamaica.” Mario talks about giving youth individual rights to access healthcare. “So, can they go to a doctor, nurse without worrying if they are old enough or if the doctor or nurse will talk back to the parents? Access is about giving them the knowledge and empowering them to go for what they need.” “The stigma is the misinformation. If you’re going to the clinic people automatically assume, you’re doing an HIV/AIDS test or getting an abortion. [So] after the community empowerment, because of the stigma maybe 15 per cent will respond and come to the clinic. The biggest issue is misinformation,” Mario says, adding that diversification of the content and how messages are shaped could possibly help. To address these issues, he wants to see more young people involved in advocacy and helping to push FAMPLAN’s messages in a diversified way. “It is a satisfying thing to do both for your own self development and community development. You’re building a network. If you put yourself out there you don’t know what can happen.”

| 11 March 2021

“I wanted to pass on my knowledge”

Candice, 18, joined the Youth Advocacy Movement (YAM) when she was 15 after being introduced to the group by the Jamaica Family Planning Association’s (FAMPLAN) youth officer, Fiona. Sharing knowledge with peers Initially, Candice, saw YAM as a space where she could learn about sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) as there was no information available elsewhere. Candice uses her knowledge and involvement with YAM to educate her peers about their sexual health and rights with hopes that they make informed choices if they choose to engage in sex. “I’ve seen teenagers get pregnant and it’s based off them never knowing routes they could take to prevent pregnancies. I figured I could play a role by learning it for myself, applying it to myself as well as talk to those around me to somewhat enlighten them about sexual and reproductive health. I just wanted to be able to learn for myself and pass on the knowledge.” Making positive changes Candice believes that sexual and reproductive health and rights are not limited to sex, but also about being empowered to make positive changes and choices. Candice has worked with the youth group to use her voice for the voiceless and make a change. “Seeing young girls divert to wanting more and because their parents were not able to provide, they turn to men. Also, I saw undue pressure being placed on girls to not have sex and that pressure unfortunately caused them to develop creative ways to go out and it so ends up that they were left with an unwanted pregnancy. I was learning not only for myself, but to spread the word. I learnt I needed to immerse myself in order to be an effective advocate.” Through her advocacy work, Candice has been to health fairs and spoken to her peers and adults about their sexual and reproductive health and rights. The impact has been positive. “In my circle I’ve seen people become more aware and more careful. In my teaching, my friends are inspired to join so I am looking to recruit soon,” she said. Breaking down barriers to contraception use Candice has faced a number of obstacles, especially around the reservations her peers have to practicing safer sex. “You can only educate someone, but you can’t force them to do what you’re promoting. You will have different people asking and you explain to them and show them different ways to approach stuff and they will outright be like ‘OK, I am still going to do my thing. This is how I am used to my thing’. So, they accept the information, but are they practicing the information? People are open minded, but it’s just for them to put the open mindedness into action.” Candice says there are parents who are not open to discussing these issues with their children and it subsequently makes the work more challenging and prohibits access to safer practices and choices. She believes it would be beneficial for parents to take a more active role in advocating healthy choices. She would also like to see more sexual and reproductive health and rights sessions delivered in schools. “Implement classes in school that are more detailed than what exists. The current lessons are basic and the most compact you’ll learn is the menstrual cycle. You’re learning enough to do your exam, not apply to real life. If this is in schools, the doctors and clinics may be more open to the reality that younger people are engaging in sex. To prevent unplanned pregnancies be more open.” “YAM has good intentions. These good intentions are definitely beneficial to the target audience. With more empowerment in the initiative we can move forward and complete the goal on a larger scale.”

| 11 March 2021

“I wanted to pass on my knowledge”

Candice, 18, joined the Youth Advocacy Movement (YAM) when she was 15 after being introduced to the group by the Jamaica Family Planning Association’s (FAMPLAN) youth officer, Fiona. Sharing knowledge with peers Initially, Candice, saw YAM as a space where she could learn about sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) as there was no information available elsewhere. Candice uses her knowledge and involvement with YAM to educate her peers about their sexual health and rights with hopes that they make informed choices if they choose to engage in sex. “I’ve seen teenagers get pregnant and it’s based off them never knowing routes they could take to prevent pregnancies. I figured I could play a role by learning it for myself, applying it to myself as well as talk to those around me to somewhat enlighten them about sexual and reproductive health. I just wanted to be able to learn for myself and pass on the knowledge.” Making positive changes Candice believes that sexual and reproductive health and rights are not limited to sex, but also about being empowered to make positive changes and choices. Candice has worked with the youth group to use her voice for the voiceless and make a change. “Seeing young girls divert to wanting more and because their parents were not able to provide, they turn to men. Also, I saw undue pressure being placed on girls to not have sex and that pressure unfortunately caused them to develop creative ways to go out and it so ends up that they were left with an unwanted pregnancy. I was learning not only for myself, but to spread the word. I learnt I needed to immerse myself in order to be an effective advocate.” Through her advocacy work, Candice has been to health fairs and spoken to her peers and adults about their sexual and reproductive health and rights. The impact has been positive. “In my circle I’ve seen people become more aware and more careful. In my teaching, my friends are inspired to join so I am looking to recruit soon,” she said. Breaking down barriers to contraception use Candice has faced a number of obstacles, especially around the reservations her peers have to practicing safer sex. “You can only educate someone, but you can’t force them to do what you’re promoting. You will have different people asking and you explain to them and show them different ways to approach stuff and they will outright be like ‘OK, I am still going to do my thing. This is how I am used to my thing’. So, they accept the information, but are they practicing the information? People are open minded, but it’s just for them to put the open mindedness into action.” Candice says there are parents who are not open to discussing these issues with their children and it subsequently makes the work more challenging and prohibits access to safer practices and choices. She believes it would be beneficial for parents to take a more active role in advocating healthy choices. She would also like to see more sexual and reproductive health and rights sessions delivered in schools. “Implement classes in school that are more detailed than what exists. The current lessons are basic and the most compact you’ll learn is the menstrual cycle. You’re learning enough to do your exam, not apply to real life. If this is in schools, the doctors and clinics may be more open to the reality that younger people are engaging in sex. To prevent unplanned pregnancies be more open.” “YAM has good intentions. These good intentions are definitely beneficial to the target audience. With more empowerment in the initiative we can move forward and complete the goal on a larger scale.”

| 11 March 2021

"I saw the opportunity to do cervical screenings"

Dr McKoy has committed his life to ensuring equality of healthcare provision for women and men at the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN). Expanding contraceptive choice Returning to Jamaica from his overseas medical studies in the 1980s, Dr McKoy was frustrated and concerned at the failure of many Jamaican males to use contraception. This led him to making a strong case to integrate male sterilization as part of FAMPLAN’s contraceptive care package. Whilst the initial response from local males was disheartening, Dr McKoy took the grassroots approach to get the buy-in of males to consider contraception use. “Someone once said it’s only by varied reiteration that unfamiliar truths can be introduced to reluctant minds. We used to go out into the countryside and give talks. In those times I came down heavily on men.” Overcoming these barriers, was the catalyst he needed to ensure that men accessed and benefitted from health and contraceptive care. Men were starting to choose vasectomies if they already had children and had no plans for more. Encouraging uptake of male healthcare Dr McKoy was an instrumental voice in the Men’s Clinic that was run by FAMPLAN, encouraging the inclusion of women at the meetings, in order to increase male participation and uptake of healthcare. “When we as men get sick with our prostate it is women who are going to look after us. But we have to put interest in our own self to offset it before it puts us in that situation where we can’t help yourself. It came down to that and the males eventually started coming. The health education got out and men started being more confident in the health services.” Health and wellbeing are vital McKoy advocates the importance of women taking their sexual health seriously and accessing contraceptive care. If neglected, Dr McKoy says it could be a matter of life death. He recalls a story of a young mother who was complacent towards cervical screenings and sadly died from cervical cancer - a death he says which could have been prevented. “Over the years I saw the opportunity to do cervical screenings at the clinic. The mobile unit gave us access to so many patients. We had persons who neglected to do it. One patient in particular - she was not yet 30 years old. She had three children and after every delivery she was told by the hospital to get a cervical screening. She didn’t do it and eventually got cervical cancer. When she was to do the cervical screening, she didn’t come. One morning they brought her and had to lift her up out of the car. At that time doctors said they couldn’t do anything for her. It wasn’t necessary. So, we had to go out more to meet people, educate them teach them the importance of sexual and reproductive health.” That experience was his driving force to continue the work in providing sexual and reproductive healthcare and information through community outreach.

| 16 May 2025

"I saw the opportunity to do cervical screenings"

Dr McKoy has committed his life to ensuring equality of healthcare provision for women and men at the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN). Expanding contraceptive choice Returning to Jamaica from his overseas medical studies in the 1980s, Dr McKoy was frustrated and concerned at the failure of many Jamaican males to use contraception. This led him to making a strong case to integrate male sterilization as part of FAMPLAN’s contraceptive care package. Whilst the initial response from local males was disheartening, Dr McKoy took the grassroots approach to get the buy-in of males to consider contraception use. “Someone once said it’s only by varied reiteration that unfamiliar truths can be introduced to reluctant minds. We used to go out into the countryside and give talks. In those times I came down heavily on men.” Overcoming these barriers, was the catalyst he needed to ensure that men accessed and benefitted from health and contraceptive care. Men were starting to choose vasectomies if they already had children and had no plans for more. Encouraging uptake of male healthcare Dr McKoy was an instrumental voice in the Men’s Clinic that was run by FAMPLAN, encouraging the inclusion of women at the meetings, in order to increase male participation and uptake of healthcare. “When we as men get sick with our prostate it is women who are going to look after us. But we have to put interest in our own self to offset it before it puts us in that situation where we can’t help yourself. It came down to that and the males eventually started coming. The health education got out and men started being more confident in the health services.” Health and wellbeing are vital McKoy advocates the importance of women taking their sexual health seriously and accessing contraceptive care. If neglected, Dr McKoy says it could be a matter of life death. He recalls a story of a young mother who was complacent towards cervical screenings and sadly died from cervical cancer - a death he says which could have been prevented. “Over the years I saw the opportunity to do cervical screenings at the clinic. The mobile unit gave us access to so many patients. We had persons who neglected to do it. One patient in particular - she was not yet 30 years old. She had three children and after every delivery she was told by the hospital to get a cervical screening. She didn’t do it and eventually got cervical cancer. When she was to do the cervical screening, she didn’t come. One morning they brought her and had to lift her up out of the car. At that time doctors said they couldn’t do anything for her. It wasn’t necessary. So, we had to go out more to meet people, educate them teach them the importance of sexual and reproductive health.” That experience was his driving force to continue the work in providing sexual and reproductive healthcare and information through community outreach.

| 11 March 2021

“FAMPLAN has made its mark”

Cultural barriers and stigma have threatened the work of the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN), but according to one senior healthcare provider at the Beth Jacobs Clinic in St Ann, Jamaica things have taken a positive turn, though some myths around contraceptive care seem to prevail. Committed to changing perceptions and attitudes Midwife, Dorothy, is head of maternal and child and sexual and reproductive healthcare at the Beth Jacobs Clinic and first began working with FAMPLAN in 1973. She says the organization has made its mark and reduced barriers and stigmatizing behaviour towards sexual health and contraceptive care. Cultural barriers were once often seen in families not equipped with basic knowledge about sexual health. “I remember some time ago a lady beat her daughter the first time she had her period as she believed the only way, she could see her period, is if a man had gone there [if the child was sexually active]. I had to send for her [mother] and have a session with both her and the child as to how a period works. She apologized to her daughter and said she was sorry. She never had the knowledge and she was happy for places like these where she could come and learn – both parent and child.” Working with religious groups to overcome stigma Religious groups once perpetuated stigma, so much so that women feared even walking near the FAMPLAN property. “Church women would hide and come, tell their husbands, partners or friend they are going to the doctor as they have a pain in their foot, which nuh guh suh [was not true]. Every minute you would see them looking to see if any church brother or sister came on the premises to see them as they would go back and tell the Minister because they don’t support family planning. But that was in the 90s.” Dorothy says that this has changed, and the church now participates in training sessions sexual healthcare and contraceptive choice, encouraging members to be informed about their wellbeing and reproductive rights. Navigating prevailing myths Yet despite the wealth of information and forward thinking of the communities the Beth Jacobs Clinic reaches, Dorothy says there are some prevailing myths, which if left unaddressed threaten to repeal the work of FAMPLAN. “Information sharing is important, and we try to have brochures on STIs, and issues around sexual and reproductive health and rights. But there are people who still believe sex with a virgin cures’ HIV, plus there are myths around contraceptive use too. We encourage reading. Back in the 70s, 80s, 90s we had a good library where we encouraged people to read, get books, get brochures. That is not so much now,” Dorothy says. Another challenge is ensuring women are consistent with accessing healthcare and contraception. “I saw a lady in the market who told me from the last day I did her pap smear she hasn’t done another one. That was five years ago. I had one recently - no pap smear for 14 years. I delivered her last child,” she says. Despite these challenges Dorothy remains dedicated and committed to her community knowing her work helps to improve women’s lives through choice. She is confident that the Mobile Unit with community-based distributors will be reintegrated into FAMPLAN healthcare delivery so that they can reach remote communities. “FAMPLAN has made its mark. It will never leave Jamaica or die.”

| 16 May 2025

“FAMPLAN has made its mark”

Cultural barriers and stigma have threatened the work of the Jamaica Family Planning Association (FAMPLAN), but according to one senior healthcare provider at the Beth Jacobs Clinic in St Ann, Jamaica things have taken a positive turn, though some myths around contraceptive care seem to prevail. Committed to changing perceptions and attitudes Midwife, Dorothy, is head of maternal and child and sexual and reproductive healthcare at the Beth Jacobs Clinic and first began working with FAMPLAN in 1973. She says the organization has made its mark and reduced barriers and stigmatizing behaviour towards sexual health and contraceptive care. Cultural barriers were once often seen in families not equipped with basic knowledge about sexual health. “I remember some time ago a lady beat her daughter the first time she had her period as she believed the only way, she could see her period, is if a man had gone there [if the child was sexually active]. I had to send for her [mother] and have a session with both her and the child as to how a period works. She apologized to her daughter and said she was sorry. She never had the knowledge and she was happy for places like these where she could come and learn – both parent and child.” Working with religious groups to overcome stigma Religious groups once perpetuated stigma, so much so that women feared even walking near the FAMPLAN property. “Church women would hide and come, tell their husbands, partners or friend they are going to the doctor as they have a pain in their foot, which nuh guh suh [was not true]. Every minute you would see them looking to see if any church brother or sister came on the premises to see them as they would go back and tell the Minister because they don’t support family planning. But that was in the 90s.” Dorothy says that this has changed, and the church now participates in training sessions sexual healthcare and contraceptive choice, encouraging members to be informed about their wellbeing and reproductive rights. Navigating prevailing myths Yet despite the wealth of information and forward thinking of the communities the Beth Jacobs Clinic reaches, Dorothy says there are some prevailing myths, which if left unaddressed threaten to repeal the work of FAMPLAN. “Information sharing is important, and we try to have brochures on STIs, and issues around sexual and reproductive health and rights. But there are people who still believe sex with a virgin cures’ HIV, plus there are myths around contraceptive use too. We encourage reading. Back in the 70s, 80s, 90s we had a good library where we encouraged people to read, get books, get brochures. That is not so much now,” Dorothy says. Another challenge is ensuring women are consistent with accessing healthcare and contraception. “I saw a lady in the market who told me from the last day I did her pap smear she hasn’t done another one. That was five years ago. I had one recently - no pap smear for 14 years. I delivered her last child,” she says. Despite these challenges Dorothy remains dedicated and committed to her community knowing her work helps to improve women’s lives through choice. She is confident that the Mobile Unit with community-based distributors will be reintegrated into FAMPLAN healthcare delivery so that they can reach remote communities. “FAMPLAN has made its mark. It will never leave Jamaica or die.”

| 11 March 2021

“This group is very dear to me”

Christan, 26, is committed to helping develop young people to become confident advocates for change. Christan is the executive assistant at the FAMPLAN Lenworth Jacobs Clinic. Her work overlaps with that of the Youth Action Movement (YAM), helping to foster the transitioning and development of youth into meaningful adults. Harnessing change through young advocates “FAMPLAN provides the space or capacity for young persons who they engage on a regular basis to grow — whether through outreach, rap sessions, educational sessions. The organization provides them with an opportunity to grow and build their capacity as it relates to advocating for sexual and reproductive health and rights amongst their other peers,” she said. Though she has passed on her youth officer baton, Christan, remains connected to YAM and ensures she leads by example. “When you have young adults, who are part of the organization, who lobby and advocate for the rights of other adults like themselves, then, on the other hand, you are going to have young people like Mario, Candice and Fiona who advocate for persons within their age cohort,” she said. “Transitioning out of the group and working alongside these young folks, I feel as if I can still share some of the realities they share, have one-on-one conversations with them, help them along their journey and also help myself as well, because social connectiveness is an important part of your mental health. This group is very, very, very dear to me.” Gaining confidence through volunteering With regards to its impact on her life, Christan said YAM helped her to become more of an extrovert and shaped her confidence. “I was more of an introvert and now I can get up do a wide presentation and engage other people without feeling like I do not have the capacity or expertise to bring across certain issues,” she said. However, she says that there is still a lot of sensitivity around sexual and reproductive health and rights. This can sometimes limit the conversations YAM is able to have and at times may generate fear among some of the group members. Turning members into advocates “There are certain sensitive topics that still present an issue when trying to bring it forward in certain spaces. Other challenges they [YAM members] may face are personal reservations. Although we provide them with the skillset, certain persons are still more reserved and are not able to be engaged in certain spaces. Sometimes they just want to stay in the back and issue flyers or something behind the scenes rather than being upfront.” But as the main aim of the movement is to develop advocates out of members, Christan’s conviction is helping to strengthen Yam's capacity. “To advocate you must be able to get up, stand up and speak for the persons who we classify as the voiceless or persons who are vulnerable and marginalised. I think that is one of the limitations as well. Going out and doing an HIV test and having counselling is OK, but as it relates to really standing up and advocating, being able to write a piece and send it to Parliament, being able to make certain submissions like editorial pieces. That needs to be strengthened,” says Christan.

| 16 May 2025

“This group is very dear to me”

Christan, 26, is committed to helping develop young people to become confident advocates for change. Christan is the executive assistant at the FAMPLAN Lenworth Jacobs Clinic. Her work overlaps with that of the Youth Action Movement (YAM), helping to foster the transitioning and development of youth into meaningful adults. Harnessing change through young advocates “FAMPLAN provides the space or capacity for young persons who they engage on a regular basis to grow — whether through outreach, rap sessions, educational sessions. The organization provides them with an opportunity to grow and build their capacity as it relates to advocating for sexual and reproductive health and rights amongst their other peers,” she said. Though she has passed on her youth officer baton, Christan, remains connected to YAM and ensures she leads by example. “When you have young adults, who are part of the organization, who lobby and advocate for the rights of other adults like themselves, then, on the other hand, you are going to have young people like Mario, Candice and Fiona who advocate for persons within their age cohort,” she said. “Transitioning out of the group and working alongside these young folks, I feel as if I can still share some of the realities they share, have one-on-one conversations with them, help them along their journey and also help myself as well, because social connectiveness is an important part of your mental health. This group is very, very, very dear to me.” Gaining confidence through volunteering With regards to its impact on her life, Christan said YAM helped her to become more of an extrovert and shaped her confidence. “I was more of an introvert and now I can get up do a wide presentation and engage other people without feeling like I do not have the capacity or expertise to bring across certain issues,” she said. However, she says that there is still a lot of sensitivity around sexual and reproductive health and rights. This can sometimes limit the conversations YAM is able to have and at times may generate fear among some of the group members. Turning members into advocates “There are certain sensitive topics that still present an issue when trying to bring it forward in certain spaces. Other challenges they [YAM members] may face are personal reservations. Although we provide them with the skillset, certain persons are still more reserved and are not able to be engaged in certain spaces. Sometimes they just want to stay in the back and issue flyers or something behind the scenes rather than being upfront.” But as the main aim of the movement is to develop advocates out of members, Christan’s conviction is helping to strengthen Yam's capacity. “To advocate you must be able to get up, stand up and speak for the persons who we classify as the voiceless or persons who are vulnerable and marginalised. I think that is one of the limitations as well. Going out and doing an HIV test and having counselling is OK, but as it relates to really standing up and advocating, being able to write a piece and send it to Parliament, being able to make certain submissions like editorial pieces. That needs to be strengthened,” says Christan.

| 23 January 2019

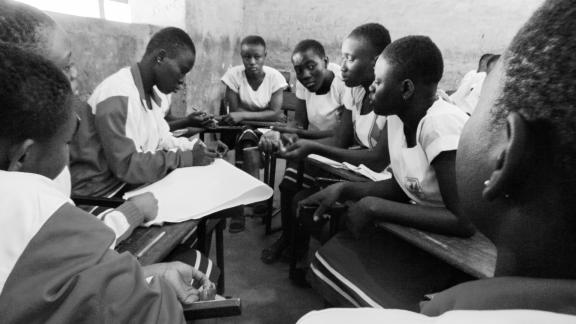

“Since the closure of the clinic ... we encounter a lot more problems in our area"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Asba Hann is the president of the Guediawaye chapter of IPPF’s Africa region youth action movement. She explains how the Global Gag Rule (GGR) cuts have deprived youth of a space to ask questions about their sexuality and seek advice on contraception. “Since the closure of the clinic, the nature of our advocacy has changed. We encounter a lot more problems in our area, above all from young people and women asking for services. ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial) was a little bit less expensive for them and in this suburb there is a lot of poverty. Our facilities as volunteers also closed. We offer information to young people but since the closure of the clinic and our space they no longer get it in the same way, because they used to come and visit us. We still do activities but it’s difficult to get the information out, so young people worry about their sexual health and can’t get the confirmation needed for their questions. Young people don’t want to be seen going to a pharmacy and getting contraception, at risk of being seen by members of the community. They preferred seeing a midwife, discreetly, and to obtain their contraception privately. Young people often also can’t afford the contraception in the clinics and pharmacies. It would be much easier for us to have a specific place to hold events with the midwives who could then explain things to young people. A lot of the teenagers here still aren’t connected to the internet and active on social media. Others work all day and can’t look at their phones, and announcements get lost when they look at all their messages at night. Being on the ground is the best way for us to connect to young people.”

| 16 May 2025

“Since the closure of the clinic ... we encounter a lot more problems in our area"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Asba Hann is the president of the Guediawaye chapter of IPPF’s Africa region youth action movement. She explains how the Global Gag Rule (GGR) cuts have deprived youth of a space to ask questions about their sexuality and seek advice on contraception. “Since the closure of the clinic, the nature of our advocacy has changed. We encounter a lot more problems in our area, above all from young people and women asking for services. ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial) was a little bit less expensive for them and in this suburb there is a lot of poverty. Our facilities as volunteers also closed. We offer information to young people but since the closure of the clinic and our space they no longer get it in the same way, because they used to come and visit us. We still do activities but it’s difficult to get the information out, so young people worry about their sexual health and can’t get the confirmation needed for their questions. Young people don’t want to be seen going to a pharmacy and getting contraception, at risk of being seen by members of the community. They preferred seeing a midwife, discreetly, and to obtain their contraception privately. Young people often also can’t afford the contraception in the clinics and pharmacies. It would be much easier for us to have a specific place to hold events with the midwives who could then explain things to young people. A lot of the teenagers here still aren’t connected to the internet and active on social media. Others work all day and can’t look at their phones, and announcements get lost when they look at all their messages at night. Being on the ground is the best way for us to connect to young people.”

| 23 January 2019

“Since the clinic closed in this town everything has been very difficult"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Betty Guèye is a midwife who used to live in Guediawaye but moved to Dakar after the closure of the clinic in the suburb of Senegal’s capital following global gag rule (GGR) funding cuts. She describes the effects of the closure and how Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) staff try to maximise the reduced service they still offer. “Since the clinic closed in this town everything has been very difficult. The majority of Senegalese are poor and we are losing clients because they cannot access the main clinic in Dakar. If they have an appointment on a Monday, after the weekend they won’t have the 200 francs (35 US cents) needed for the bus, and they will wait until Tuesday or Wednesday to come even though they are in pain. The clinic was of huge benefit to the community of Guediawaye and the surrounding suburbs as well. What we see now is that women wait until pain or infections are at a more advanced stage before they visit us in Dakar. Another effect is that if they need to update their contraception they will exceed the date required for the new injection or pill and then get pregnant as a result. In addition, raising awareness of sexual health in schools and neighbourhoods is a key part of our work. Religion and the lack of openness in the parent-child relationship inhibit these conversations in Senegal, and so young people don’t tell their parents when they have sexual health problems. We were very present in this area and now we only appear much more rarely in their lives, which has had negative consequences for the health of our young people. If we were still there as before, there would be fewer teenage pregnancies as well, with the advice and contraception that we provide. However, we hand out medication, we care for the community and we educate them when we can, when we are here and we have the money to do so. Our prices remain the same and they are competitive compared with the private clinics and pharmacies in the area. Young people will tell you that they are closer to the midwives and nurses here than to their parents. They can tell them anything. If a girl tells me she has had sex I can give her the morning after pill, but if she goes to the local health center she may feel she is being watched by her neighbours.” Ndeye Yacine Touré is a midwife who regularly fields calls from young women in Guediawaye seeking advice on their sexual health, and who no longer know where to turn. The closure of the Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) clinic in their area has left them seeking often desperate solutions to the taboo of having a child outside of marriage. “Many of our colleagues lost their jobs, and these were people who were supporting their families. It was a loss for the area as a whole, because this is a very poor neighbourhood where people don’t have many options in life. ASBEF Guediawaye was their main source of help because they came here for consultations but also for confidential advice. The services we offer at ASBEF are special, in a way, especially in the area of family planning. Women were at ease at the clinic, but since then there is a gap in their lives. The patients call us day and night wanting advice, asking how to find the main clinic in Dakar. Some say they no longer get check-ups or seek help because they lack the money to go elsewhere. Others say they miss certain midwives or nurses. We make use of emergency funds in several ways. We do pop-up events. I also give them my number and tell them how to get to the clinic in central Dakar, and reassure them that it will all be confidential and that they can seek treatment there. In Senegal, a girl having sex outside marriage isn’t accepted. Some young women were taking contraception secretly, but since the closure of the clinic it’s no longer possible. Some of them got pregnant as a result. They don’t want to bump into their mother at the public clinic so they just stop taking contraception. In Senegal, a girl having sex outside marriage isn’t accepted. The impact on young people is particularly serious. Some tell me they know they have a sexually transmitted infection but they are too afraid to go to the hospital and get it treated. Before they could talk to us and tell us that they had sex, and we could help them. They have to hide now and some seek unsafe abortions. ”

| 16 May 2025

“Since the clinic closed in this town everything has been very difficult"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Betty Guèye is a midwife who used to live in Guediawaye but moved to Dakar after the closure of the clinic in the suburb of Senegal’s capital following global gag rule (GGR) funding cuts. She describes the effects of the closure and how Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) staff try to maximise the reduced service they still offer. “Since the clinic closed in this town everything has been very difficult. The majority of Senegalese are poor and we are losing clients because they cannot access the main clinic in Dakar. If they have an appointment on a Monday, after the weekend they won’t have the 200 francs (35 US cents) needed for the bus, and they will wait until Tuesday or Wednesday to come even though they are in pain. The clinic was of huge benefit to the community of Guediawaye and the surrounding suburbs as well. What we see now is that women wait until pain or infections are at a more advanced stage before they visit us in Dakar. Another effect is that if they need to update their contraception they will exceed the date required for the new injection or pill and then get pregnant as a result. In addition, raising awareness of sexual health in schools and neighbourhoods is a key part of our work. Religion and the lack of openness in the parent-child relationship inhibit these conversations in Senegal, and so young people don’t tell their parents when they have sexual health problems. We were very present in this area and now we only appear much more rarely in their lives, which has had negative consequences for the health of our young people. If we were still there as before, there would be fewer teenage pregnancies as well, with the advice and contraception that we provide. However, we hand out medication, we care for the community and we educate them when we can, when we are here and we have the money to do so. Our prices remain the same and they are competitive compared with the private clinics and pharmacies in the area. Young people will tell you that they are closer to the midwives and nurses here than to their parents. They can tell them anything. If a girl tells me she has had sex I can give her the morning after pill, but if she goes to the local health center she may feel she is being watched by her neighbours.” Ndeye Yacine Touré is a midwife who regularly fields calls from young women in Guediawaye seeking advice on their sexual health, and who no longer know where to turn. The closure of the Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) clinic in their area has left them seeking often desperate solutions to the taboo of having a child outside of marriage. “Many of our colleagues lost their jobs, and these were people who were supporting their families. It was a loss for the area as a whole, because this is a very poor neighbourhood where people don’t have many options in life. ASBEF Guediawaye was their main source of help because they came here for consultations but also for confidential advice. The services we offer at ASBEF are special, in a way, especially in the area of family planning. Women were at ease at the clinic, but since then there is a gap in their lives. The patients call us day and night wanting advice, asking how to find the main clinic in Dakar. Some say they no longer get check-ups or seek help because they lack the money to go elsewhere. Others say they miss certain midwives or nurses. We make use of emergency funds in several ways. We do pop-up events. I also give them my number and tell them how to get to the clinic in central Dakar, and reassure them that it will all be confidential and that they can seek treatment there. In Senegal, a girl having sex outside marriage isn’t accepted. Some young women were taking contraception secretly, but since the closure of the clinic it’s no longer possible. Some of them got pregnant as a result. They don’t want to bump into their mother at the public clinic so they just stop taking contraception. In Senegal, a girl having sex outside marriage isn’t accepted. The impact on young people is particularly serious. Some tell me they know they have a sexually transmitted infection but they are too afraid to go to the hospital and get it treated. Before they could talk to us and tell us that they had sex, and we could help them. They have to hide now and some seek unsafe abortions. ”

| 22 January 2019

“I used to attend the clinic regularly and then one day I didn’t know what happened. The clinic just shut down"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Maguette Mbow, a 33-year-old homemaker, describes how the closure of Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in Guediawaye, a suburb of Dakar, has affected her, and explains the difficulties with the alternative providers available. She spoke about how the closure of her local clinic has impacted her life at a pop-up clinic set up for the day at a school in Guediawaye. “I heard that ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial), was doing consultations here today and I dropped everything at home to come. There was a clinic here in Guediawaye but we don’t have it anymore. I’m here for family planning because that’s what I used to get at the clinic; it was their strong point. I take the Pill and I came to change the type I take, but the midwife advised me today to keep taking the same one. I’ve used the pill between my pregnancies. I have two children aged 2 and 6, but for now I’m not sure if I want a third child. When the clinic closed, I started going to the public facilities instead. There is always an enormous queue. You can get there in the morning and wait until 3pm for a consultation. (The closure) has affected everyone here very seriously. All my friends and family went to ASBEF Guediawaye, but now we are in the other public and private clinics receiving a really poor service. I had all of my pre-natal care at ASBEF and when I was younger I used the services for young people as well. They helped me take the morning after pill a few times and that really left its mark on me. They are great with young people; they are knowledgeable and really good with teenagers. There are still taboos surrounding sexuality in Senegal but they know how to handle them. These days, when ASBEF come to Guediawaye they have to set up in different places each time. It’s a bit annoying because if you know a place well and it’s full of well-trained people who you know personally, you feel more at ease. I would like things to go back to how they were before, and for the clinic to reopen. I would also have liked to send my children there one day when the time came, to benefit from the same service. Sometimes I travel right into Dakar for a consultation at the ASBEF headquarters, but often I don’t have the money.” Fatou Bimtou Diop, 20, is a final year student at Lycée Seydina Limamou Laye in Guediawaye. She explains why the closure of the Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in her area in 2017 means she no longer regularly seeks advice on her sexual health. “I came here today for a consultation. I haven’t been for two years because the clinic closed. I don’t know why that happened but I would really like that decision to be reversed. Yes, there are other clinics here but I don’t feel as relaxed as with ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial). I used to feel really at ease because there were other young people like me there. In the other clinics I know I might see someone’s mother or my aunties and it worries me too much. They explained things well and the set-up felt secure. We could talk about the intimate problems that were affecting us to the ASBEF staff. I went because I have really painful periods, for example. Sometimes I wouldn’t have the nerve to ask certain questions but my friends who went to the ASBEF clinic would ask and then tell me the responses that they got. These days we end up talking a lot about girls who are 14,15 years old who are pregnant. When the ASBEF clinic was there it was really rare to see a girl that young with a baby but now it happens very frequently. A friend’s younger sister has a little boy now and she had to have a caesarian section because she’s younger than us. The clinic in Dakar is too far away. I have to go to school during the day so I can’t take the time off. I came to the session today at school and it was good to discuss my problems, but it took quite a long time to get seen by a midwife.” Ngouye Cissé, a 30-year-old woman who gave birth to her first child in her early teens, but who has since used regular contraception provided by ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial). She visits the association’s pop-up clinics whenever they are in Guediawaye. “I used to attend the clinic regularly and then one day I didn’t know what happened. The clinic just shut down. Senegal’s economic situation is difficult and we don’t have a lot of money. The fees for a consultation are quite expensive, but when ASBEF does come into the community it’s free. I most recently visited the pop-up clinic because I was having some vaginal discharge and I didn’t know why. The midwife took care of me and gave me some advice and medication. Before I came here for my check-up, the public hospital was asking me to do a lot of tests and I was afraid I had some kind of terrible disease. But when I came to the ASBEF midwife simply listened to me, explained what I had, and then gave me the right medication straight away. I feel really relieved. I’m divorced and I have three boys. I had pre-natal care with ASBEF for the first two pregnancies, but with the third, my 2-year-old son, I had to go to a public hospital. The experiences couldn’t be more different. First, there is a big difference in price, as ASBEF is much cheaper. Also, at the ASBEF clinic we are really listened to. The midwife explains things and gives me information. We can talk about our problems openly and without fear, unlike in other health centers. What I see now that the clinic has closed is a lot more pregnant young girls, problems with STIs and in order to get treatment we have to go to the public and private clinics. When people hear that ASBEF is back in town there is a huge rush to get a consultation, because the need is there but people don’t know where else to go. Unfortunately, the transport to go to the clinic in Dakar costs a lot of money for us that we don’t have. Some households don’t even have enough to eat. There isn’t a huge difference between the consultations in the old clinic and the pop-up events that ASBEF organize. They still listen to you properly and it’s well organized. It just takes longer to get seen.” Moudel Bassoum, a 22-year student studying NGO management in Dakar, explains why she has been unable to replace the welcome and care she received at the now closed Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in her hometown of Guediawaye, but still makes us of the pop-up clinic when it is available. “I used to go to the clinic regularly but since it closed, we only see the staff rarely around here. I came with my friends today for a free check-up. I told the whole neighbourhood that ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial) were doing a pop-up clinic today so that they could come for free consultations. It’s not easy to get to the main clinic in Dakar for us. The effects of the closure are numerous, especially on young people. It helped us so much but now I hear a lot more about teenage pregnancies and STIs, not to mention girls trying to abort pregnancies by themselves. When my friend had an infection she went all the way into Dakar for the consultation because the public clinic is more expensive. I would much rather talk to a woman about this type of problem and at the public clinic you don’t get to pick who you talk to. You have to say everything in front of everyone. I don’t think the service we receive since the closure is different when the ASBEF clinic set up here for the day, but the staff are usually not the same and it’s less frequent. It’s free so when they do come there are a lot of people. I would really like the clinic to be re-established when I have a baby one day. I want that welcome, and to know that they will listen to you.”

| 16 May 2025

“I used to attend the clinic regularly and then one day I didn’t know what happened. The clinic just shut down"

Senegal’s IPPF Member Association, Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial (ASBEF) ran two clinics in the capital, Dakar, until funding was cut in 2017 due to the reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule (GGR) by the US administration. The ASBEF clinic in the struggling suburb of Guediawaye was forced to close as a result of the GGR, leaving just the main headquarters in the heart of the city. The GGR prohibits foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who receive US assistance from providing abortion care services, even with the NGO’s non-US funds. Abortion is illegal in Senegal except when three doctors agree the procedure is required to save a mother’s life. ASBEF applied for emergency funds and now offers an alternative service to the population of Guediawaye, offering sexual and reproductive health services through pop-up clinics. Maguette Mbow, a 33-year-old homemaker, describes how the closure of Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in Guediawaye, a suburb of Dakar, has affected her, and explains the difficulties with the alternative providers available. She spoke about how the closure of her local clinic has impacted her life at a pop-up clinic set up for the day at a school in Guediawaye. “I heard that ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial), was doing consultations here today and I dropped everything at home to come. There was a clinic here in Guediawaye but we don’t have it anymore. I’m here for family planning because that’s what I used to get at the clinic; it was their strong point. I take the Pill and I came to change the type I take, but the midwife advised me today to keep taking the same one. I’ve used the pill between my pregnancies. I have two children aged 2 and 6, but for now I’m not sure if I want a third child. When the clinic closed, I started going to the public facilities instead. There is always an enormous queue. You can get there in the morning and wait until 3pm for a consultation. (The closure) has affected everyone here very seriously. All my friends and family went to ASBEF Guediawaye, but now we are in the other public and private clinics receiving a really poor service. I had all of my pre-natal care at ASBEF and when I was younger I used the services for young people as well. They helped me take the morning after pill a few times and that really left its mark on me. They are great with young people; they are knowledgeable and really good with teenagers. There are still taboos surrounding sexuality in Senegal but they know how to handle them. These days, when ASBEF come to Guediawaye they have to set up in different places each time. It’s a bit annoying because if you know a place well and it’s full of well-trained people who you know personally, you feel more at ease. I would like things to go back to how they were before, and for the clinic to reopen. I would also have liked to send my children there one day when the time came, to benefit from the same service. Sometimes I travel right into Dakar for a consultation at the ASBEF headquarters, but often I don’t have the money.” Fatou Bimtou Diop, 20, is a final year student at Lycée Seydina Limamou Laye in Guediawaye. She explains why the closure of the Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in her area in 2017 means she no longer regularly seeks advice on her sexual health. “I came here today for a consultation. I haven’t been for two years because the clinic closed. I don’t know why that happened but I would really like that decision to be reversed. Yes, there are other clinics here but I don’t feel as relaxed as with ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial). I used to feel really at ease because there were other young people like me there. In the other clinics I know I might see someone’s mother or my aunties and it worries me too much. They explained things well and the set-up felt secure. We could talk about the intimate problems that were affecting us to the ASBEF staff. I went because I have really painful periods, for example. Sometimes I wouldn’t have the nerve to ask certain questions but my friends who went to the ASBEF clinic would ask and then tell me the responses that they got. These days we end up talking a lot about girls who are 14,15 years old who are pregnant. When the ASBEF clinic was there it was really rare to see a girl that young with a baby but now it happens very frequently. A friend’s younger sister has a little boy now and she had to have a caesarian section because she’s younger than us. The clinic in Dakar is too far away. I have to go to school during the day so I can’t take the time off. I came to the session today at school and it was good to discuss my problems, but it took quite a long time to get seen by a midwife.” Ngouye Cissé, a 30-year-old woman who gave birth to her first child in her early teens, but who has since used regular contraception provided by ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial). She visits the association’s pop-up clinics whenever they are in Guediawaye. “I used to attend the clinic regularly and then one day I didn’t know what happened. The clinic just shut down. Senegal’s economic situation is difficult and we don’t have a lot of money. The fees for a consultation are quite expensive, but when ASBEF does come into the community it’s free. I most recently visited the pop-up clinic because I was having some vaginal discharge and I didn’t know why. The midwife took care of me and gave me some advice and medication. Before I came here for my check-up, the public hospital was asking me to do a lot of tests and I was afraid I had some kind of terrible disease. But when I came to the ASBEF midwife simply listened to me, explained what I had, and then gave me the right medication straight away. I feel really relieved. I’m divorced and I have three boys. I had pre-natal care with ASBEF for the first two pregnancies, but with the third, my 2-year-old son, I had to go to a public hospital. The experiences couldn’t be more different. First, there is a big difference in price, as ASBEF is much cheaper. Also, at the ASBEF clinic we are really listened to. The midwife explains things and gives me information. We can talk about our problems openly and without fear, unlike in other health centers. What I see now that the clinic has closed is a lot more pregnant young girls, problems with STIs and in order to get treatment we have to go to the public and private clinics. When people hear that ASBEF is back in town there is a huge rush to get a consultation, because the need is there but people don’t know where else to go. Unfortunately, the transport to go to the clinic in Dakar costs a lot of money for us that we don’t have. Some households don’t even have enough to eat. There isn’t a huge difference between the consultations in the old clinic and the pop-up events that ASBEF organize. They still listen to you properly and it’s well organized. It just takes longer to get seen.” Moudel Bassoum, a 22-year student studying NGO management in Dakar, explains why she has been unable to replace the welcome and care she received at the now closed Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial clinic in her hometown of Guediawaye, but still makes us of the pop-up clinic when it is available. “I used to go to the clinic regularly but since it closed, we only see the staff rarely around here. I came with my friends today for a free check-up. I told the whole neighbourhood that ASBEF (Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial) were doing a pop-up clinic today so that they could come for free consultations. It’s not easy to get to the main clinic in Dakar for us. The effects of the closure are numerous, especially on young people. It helped us so much but now I hear a lot more about teenage pregnancies and STIs, not to mention girls trying to abort pregnancies by themselves. When my friend had an infection she went all the way into Dakar for the consultation because the public clinic is more expensive. I would much rather talk to a woman about this type of problem and at the public clinic you don’t get to pick who you talk to. You have to say everything in front of everyone. I don’t think the service we receive since the closure is different when the ASBEF clinic set up here for the day, but the staff are usually not the same and it’s less frequent. It’s free so when they do come there are a lot of people. I would really like the clinic to be re-established when I have a baby one day. I want that welcome, and to know that they will listen to you.”

| 11 March 2021

“There’s a lot going through these teenagers’ minds”