Spotlight

A selection of stories from across the Federation

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in the face of growing opposition and the rise of the far right? These victories for sexual and reproductive rights and health are the result of relentless grassroots work and advocacy by our Member Associations, in partnership with community organizations, allied politicians, and the mobilization of public opinion.

Most Popular This Week

Advances in Sexual and Reproductive Rights and Health: 2024 in Review

Let’s take a leap back in time to the beginning of 2024: In twelve months, what victories has our movement managed to secure in t

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan's Rising HIV Crisis: A Call for Action

On World AIDS Day, we commemorate the remarkable achievements of IPPF Member Associations in their unwavering commitment to combating the HIV epidemic.

Ensuring SRHR in Humanitarian Crises: What You Need to Know

Over the past two decades, global forced displacement has consistently increased, affecting an estimated 114 million people as of mid-2023.

Estonia, Nepal, Namibia, Japan, Thailand

The Rainbow Wave for Marriage Equality

Love wins! The fight for marriage equality has seen incredible progress worldwide, with a recent surge in legalizations.

France, Germany, Poland, United Kingdom, United States, Colombia, India, Tunisia

Abortion Rights: Latest Decisions and Developments around the World

Over the past 30 years, more than

Palestine

In their own words: The people providing sexual and reproductive health care under bombardment in Gaza

Week after week, heavy Israeli bombardment from air, land, and sea, has continued across most of the Gaza Strip.

Vanuatu

When getting to the hospital is difficult, Vanuatu mobile outreach can save lives

In the mountains of Kumera on Tanna Island, Vanuatu, the village women of Kamahaul normally spend over 10,000 Vatu ($83 USD) to travel to the nearest hospital.

Filter our stories by:

- Afghan Family Guidance Association

- Albanian Center for Population and Development

- Asociación Pro-Bienestar de la Familia Colombiana

- Associação Moçambicana para Desenvolvimento da Família

- Association Béninoise pour la Promotion de la Famille

- Association Burundaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial

- Association Malienne pour la Protection et la Promotion de la Famille

- Association pour le Bien-Etre Familial/Naissances Désirables

- Association Sénégalaise pour le Bien-Étre Familial

- Association Togolaise pour le Bien-Etre Familial

- Association Tunisienne de la Santé de la Reproduction

- Botswana Family Welfare Association

- Cameroon National Association for Family Welfare

- Cook Islands Family Welfare Association

- Eesti Seksuaaltervise Liit / Estonian Sexual Health Association

- (-) Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia

- Family Planning Association of India

- Family Planning Association of Malawi

- Family Planning Association of Nepal

- Family Planning Association of Sri Lanka

- Family Planning Association of Trinidad and Tobago

- Foundation for the Promotion of Responsible Parenthood - Aruba

- Indonesian Planned Parenthood Association

- Jamaica Family Planning Association

- Kazakhstan Association on Sexual and Reproductive Health (KMPA)

- Kiribati Family Health Association

- Lesotho Planned Parenthood Association

- Mouvement Français pour le Planning Familial

- Palestinian Family Planning and Protection Association (PFPPA)

- (-) Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana

- Planned Parenthood Association of Thailand

- Planned Parenthood Association of Zambia

- Planned Parenthood Federation of America

- Planned Parenthood Federation of Nigeria

- Pro Familia - Germany

- Rahnuma-Family Planning Association of Pakistan

- Reproductive & Family Health Association of Fiji

- Reproductive Health Association of Cambodia (RHAC)

- Reproductive Health Uganda

- Somaliland Family Health Association

- Sudan Family Planning Association

- Tonga Family Health Association

- Vanuatu Family Health Association

| 28 July 2020

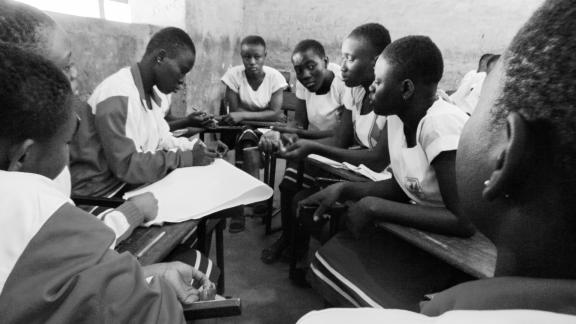

"I wanted to protect girls from violence – like early marriage – and I wanted to change people’s wrong perceptions about sex and sexuality"

Seventeen-year-old student Jumeya Mohammed Amin started educating other people about sexual and reproductive health when she was 14 years old. She trained as a ‘change agent’ for her community through the Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia’s south west office in Jimma, the capital of Oromia region. Amin comes from a small, conservative town about 20km outside the city. "I wanted to protect girls from violence – like early marriage – and I wanted to change people’s wrong perceptions about sex and sexuality, because they [men in her community] start having sex with girls at a young age, even with girls as young as nine years old, because of a lack of education." "They suddenly had to act like grown-up women" "Before I started this training I saw the majority of students having sex early and getting pregnant because of a lack of information, and they would have to leave home and school. Boys would be disciplined and if they were seen doing things on campus, expelled. Girls younger than me at the time were married. The youngest was only nine. They would have to go back home and could not play anymore or go to school. They suddenly had to act like grown-up women, like old ladies. They never go back to school after marriage. My teacher chose me for this training and told me about the programme. I like the truth so I was not afraid. I heard about a lot of problems out there during my training and I told myself I had to be strong and go and fight this." "I have a brother and four sisters and I practiced my training on my family first. They were so shocked by what I was saying they were silent. Even on the second day, they said nothing. On the third day, I told them I was going to teach people in schools this, so I asked them why they had stayed silent. They told me that because of cultural and religious issues, people would not accept these ideas and stories, but they gave me permission to go and do it. Because of my efforts, people in my school have not started having sex early and the girls get free sanitary pads through the clubs so they no longer need to stay home during periods." Training hundreds of her peers "I know people in my community who have unplanned pregnancies consult traditional healers [for abortions] and take drugs and they suffer. I know one girl from 10th grade who was 15 years old and died from this in 2017. The healers sometimes use tree leaves in their concoctions. We tell them where they can go and get different [safe abortion] services. The first round of trainings I did was with 400 students over four months and eight sessions in 2017. Last year, I trained 600 people and this year in the first trimester of school I trained 400. When students finish the course, they want to do it again, and when we forget we have a session, they come and remind me. At school, they call me a teacher. I’d like to be a doctor and this training has really made me want to do that more."

| 16 May 2025

"I wanted to protect girls from violence – like early marriage – and I wanted to change people’s wrong perceptions about sex and sexuality"

Seventeen-year-old student Jumeya Mohammed Amin started educating other people about sexual and reproductive health when she was 14 years old. She trained as a ‘change agent’ for her community through the Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia’s south west office in Jimma, the capital of Oromia region. Amin comes from a small, conservative town about 20km outside the city. "I wanted to protect girls from violence – like early marriage – and I wanted to change people’s wrong perceptions about sex and sexuality, because they [men in her community] start having sex with girls at a young age, even with girls as young as nine years old, because of a lack of education." "They suddenly had to act like grown-up women" "Before I started this training I saw the majority of students having sex early and getting pregnant because of a lack of information, and they would have to leave home and school. Boys would be disciplined and if they were seen doing things on campus, expelled. Girls younger than me at the time were married. The youngest was only nine. They would have to go back home and could not play anymore or go to school. They suddenly had to act like grown-up women, like old ladies. They never go back to school after marriage. My teacher chose me for this training and told me about the programme. I like the truth so I was not afraid. I heard about a lot of problems out there during my training and I told myself I had to be strong and go and fight this." "I have a brother and four sisters and I practiced my training on my family first. They were so shocked by what I was saying they were silent. Even on the second day, they said nothing. On the third day, I told them I was going to teach people in schools this, so I asked them why they had stayed silent. They told me that because of cultural and religious issues, people would not accept these ideas and stories, but they gave me permission to go and do it. Because of my efforts, people in my school have not started having sex early and the girls get free sanitary pads through the clubs so they no longer need to stay home during periods." Training hundreds of her peers "I know people in my community who have unplanned pregnancies consult traditional healers [for abortions] and take drugs and they suffer. I know one girl from 10th grade who was 15 years old and died from this in 2017. The healers sometimes use tree leaves in their concoctions. We tell them where they can go and get different [safe abortion] services. The first round of trainings I did was with 400 students over four months and eight sessions in 2017. Last year, I trained 600 people and this year in the first trimester of school I trained 400. When students finish the course, they want to do it again, and when we forget we have a session, they come and remind me. At school, they call me a teacher. I’d like to be a doctor and this training has really made me want to do that more."

| 28 July 2020

"I'm a volunteer here, so it’s mental satisfaction I get from doing this"

Youth leader Nebiyu Ephirem, 26, has been staffing the phones at a hotline for young people who have questions about sexual and reproductive health (SRH) since it started in 2017 in Ethiopia’s Oromia region. The helpline has two phones and is free, anonymous and open six days a week. The helpline is aimed at people aged 17-26 who are curious about SRH but are too shy or afraid to ask others about topics such as contraception, menstruation, and diseases. The hotline also advises people dealing with emergencies following unprotected sex and issues such as unintended pregnancy and concerns over sexually transmitted infections (STIs), by referring people to their nearest clinic. About 65 to 70 percent of the callers are female. Ephirem also trains other people about SRH and how to educate more young people about this. Being on call for his community “Most days, I get about 30 to 40 calls and on a Saturday, around 50. People ask about contraceptive methods like pills and emergency contraceptives and depo provera [three-month injectable contraceptive], about the spread of STIs and HIV and how to prevent it, and about menstruation and sanitation. I give my suggestions and then they come and use Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia (FGAE) services, or I refer people to clinics all over the country. There are seven FGAE clinics in this area and dozens of private clinics. Young people need information about STIs before they come to the clinic, and when they want a service they can know where the clinics are. Most of them need information about menstruation and contraception. They fear discussing this openly with family and due to religious beliefs, so people like to call me. Culturally, people used to not want to discuss sexual issues. We took the information from IPPF documents and translated them into the two local languages of Oromia and Amharic, with the help of university lecturers. After four years, even the religious leaders did this training. We have trained university students, teachers and many more people to be trainers and 30 of them graduated. They [the people who dropped out] did not want to hear about the names in the local language of body parts. Most of the ones who stayed were boys and girls, but now we have women doing this. [At first], they were laughing and said: ‘How could you talk like this? It’s shameful. But slowly, they became aware. They now talk to me, they discuss things with their parents, families, even teachers at school and friends.” Lack of sex education There is no sex education in Ethiopia’s national curriculum but youth groups and activists like Ephirem and his colleagues go into schools and teach people through school clubs. “This year [2019] up to June we trained 16,000 people and reached 517,725 adolescents and young people aged 10 to 24 through the helpline, social media – Facebook, Twitter and YouTube – workshops, radio talk shows and libraries.” A banner in Jimma town promotes the helpline and its number 8155, as does Jimma FM radio. “The target for reaching people in school was 5,400. We achieved 11,658. The most effective way to reach people is at school. At the coffee plantation sites we reach a lot of people.” The minimum family size around here is about five and the maximum we see is 10 to 12. In our culture, children are [considered as a sign of] wealth and people think they are blessed [if they have many]. When we go to schools to teach them, there are kids that already have kids. But after we teach them, they generally want to finish education and have kids at 20-25-years-old. We tell people they have to have kids related to the economy and to their incomes and we calculate the costs to feed and educate them. I’m a volunteer here, so it’s mental satisfaction I get from doing this. I get 1000 Ethiopian Birr [roughly USD 30] per month for transport costs. I am also studying marketing at university and want to become a business consultant.”

| 17 May 2025

"I'm a volunteer here, so it’s mental satisfaction I get from doing this"

Youth leader Nebiyu Ephirem, 26, has been staffing the phones at a hotline for young people who have questions about sexual and reproductive health (SRH) since it started in 2017 in Ethiopia’s Oromia region. The helpline has two phones and is free, anonymous and open six days a week. The helpline is aimed at people aged 17-26 who are curious about SRH but are too shy or afraid to ask others about topics such as contraception, menstruation, and diseases. The hotline also advises people dealing with emergencies following unprotected sex and issues such as unintended pregnancy and concerns over sexually transmitted infections (STIs), by referring people to their nearest clinic. About 65 to 70 percent of the callers are female. Ephirem also trains other people about SRH and how to educate more young people about this. Being on call for his community “Most days, I get about 30 to 40 calls and on a Saturday, around 50. People ask about contraceptive methods like pills and emergency contraceptives and depo provera [three-month injectable contraceptive], about the spread of STIs and HIV and how to prevent it, and about menstruation and sanitation. I give my suggestions and then they come and use Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia (FGAE) services, or I refer people to clinics all over the country. There are seven FGAE clinics in this area and dozens of private clinics. Young people need information about STIs before they come to the clinic, and when they want a service they can know where the clinics are. Most of them need information about menstruation and contraception. They fear discussing this openly with family and due to religious beliefs, so people like to call me. Culturally, people used to not want to discuss sexual issues. We took the information from IPPF documents and translated them into the two local languages of Oromia and Amharic, with the help of university lecturers. After four years, even the religious leaders did this training. We have trained university students, teachers and many more people to be trainers and 30 of them graduated. They [the people who dropped out] did not want to hear about the names in the local language of body parts. Most of the ones who stayed were boys and girls, but now we have women doing this. [At first], they were laughing and said: ‘How could you talk like this? It’s shameful. But slowly, they became aware. They now talk to me, they discuss things with their parents, families, even teachers at school and friends.” Lack of sex education There is no sex education in Ethiopia’s national curriculum but youth groups and activists like Ephirem and his colleagues go into schools and teach people through school clubs. “This year [2019] up to June we trained 16,000 people and reached 517,725 adolescents and young people aged 10 to 24 through the helpline, social media – Facebook, Twitter and YouTube – workshops, radio talk shows and libraries.” A banner in Jimma town promotes the helpline and its number 8155, as does Jimma FM radio. “The target for reaching people in school was 5,400. We achieved 11,658. The most effective way to reach people is at school. At the coffee plantation sites we reach a lot of people.” The minimum family size around here is about five and the maximum we see is 10 to 12. In our culture, children are [considered as a sign of] wealth and people think they are blessed [if they have many]. When we go to schools to teach them, there are kids that already have kids. But after we teach them, they generally want to finish education and have kids at 20-25-years-old. We tell people they have to have kids related to the economy and to their incomes and we calculate the costs to feed and educate them. I’m a volunteer here, so it’s mental satisfaction I get from doing this. I get 1000 Ethiopian Birr [roughly USD 30] per month for transport costs. I am also studying marketing at university and want to become a business consultant.”

| 16 July 2020

"Before, there was no safe abortion"

Rewda Kedir works as a midwife in a rural area of the Oromia region in southwest Ethiopia. Only 14% of married women are using any method of contraception here. The government hospital Rewda works in is supported to provide a full range of sexual and reproductive healthcare, which includes providing free contraceptives and comprehensive abortion care. In January 2017, the maternal healthcare clinic faced shortages of contraceptives after the US administration reactivated and expanded the Global Gag Rule, which does not allow any funding to go to organizations associated with providing abortion care. Fortunately in this case, the shortages only lasted a month due to the government of the Netherlands stepping in and matching lost funding. “Before, we had a shortage of contraceptive pills and emergency contraceptives. We would have to give people prescriptions and they would go to private clinics and where they had to pay," Rewda tells us. "When I first came to this clinic, there was a real shortage of people trained in family planning. I was the only one. Now there are many people trained on family planning, and when I’m not here, people can help." "There used to be a shortage of choice and alternatives, and now there are many. And the implant procedures are better because there are newer products that are much smaller so putting them in is less invasive.” Opening a dialogue on contraception The hospital has been providing medical abortions for six years. “Before, there was no safe abortion," says Rewda. She explains how people would go to 'traditional' healers and then come to the clinic with complications like sepsis, bleeding, anaemia and toxic shock. If they had complications or infections above nine weeks, Rewda and her colleagues would send them to Jimma, the regional capital. "Before, it was very difficult to persuade them to use family planning, and we had to have a lot of conversations. Now, they come 45 days after delivery to speak to us about this and get their babies immunised," she explains. "They want contraceptives to space out their children. Sometimes their husbands don’t like them coming to get family planning so we have to lock their appointment cards away. Their husbands want more children and they think that women who do not keep having their children will go with other men." "More kids, more wealth" Rewda tells us that they've used family counselling to try and persuade men to reconsider their ideas about contraception, by explaining to them that continuously giving birth under unsafe circumstances can affect a woman's health and might lead to maternal death, damage the uterus and lead to long-term complications. "Here, people believe that more kids means more wealth, and religion restricts family planning services. Before, they did not have good training on family planning and abortion. Now, women that have abortions get proper care and the counseling and education has improved. There are still unsafe abortions but they have really reduced. We used to see about 40 a year and now it’s one or two." However, problems still exist. "There are some complications, like irregular bleeding from some contraceptives," Rewda says, and that "women still face conflict with their husbands over family planning and sometimes have to go to court to fight this or divorce them.”

| 17 May 2025

"Before, there was no safe abortion"

Rewda Kedir works as a midwife in a rural area of the Oromia region in southwest Ethiopia. Only 14% of married women are using any method of contraception here. The government hospital Rewda works in is supported to provide a full range of sexual and reproductive healthcare, which includes providing free contraceptives and comprehensive abortion care. In January 2017, the maternal healthcare clinic faced shortages of contraceptives after the US administration reactivated and expanded the Global Gag Rule, which does not allow any funding to go to organizations associated with providing abortion care. Fortunately in this case, the shortages only lasted a month due to the government of the Netherlands stepping in and matching lost funding. “Before, we had a shortage of contraceptive pills and emergency contraceptives. We would have to give people prescriptions and they would go to private clinics and where they had to pay," Rewda tells us. "When I first came to this clinic, there was a real shortage of people trained in family planning. I was the only one. Now there are many people trained on family planning, and when I’m not here, people can help." "There used to be a shortage of choice and alternatives, and now there are many. And the implant procedures are better because there are newer products that are much smaller so putting them in is less invasive.” Opening a dialogue on contraception The hospital has been providing medical abortions for six years. “Before, there was no safe abortion," says Rewda. She explains how people would go to 'traditional' healers and then come to the clinic with complications like sepsis, bleeding, anaemia and toxic shock. If they had complications or infections above nine weeks, Rewda and her colleagues would send them to Jimma, the regional capital. "Before, it was very difficult to persuade them to use family planning, and we had to have a lot of conversations. Now, they come 45 days after delivery to speak to us about this and get their babies immunised," she explains. "They want contraceptives to space out their children. Sometimes their husbands don’t like them coming to get family planning so we have to lock their appointment cards away. Their husbands want more children and they think that women who do not keep having their children will go with other men." "More kids, more wealth" Rewda tells us that they've used family counselling to try and persuade men to reconsider their ideas about contraception, by explaining to them that continuously giving birth under unsafe circumstances can affect a woman's health and might lead to maternal death, damage the uterus and lead to long-term complications. "Here, people believe that more kids means more wealth, and religion restricts family planning services. Before, they did not have good training on family planning and abortion. Now, women that have abortions get proper care and the counseling and education has improved. There are still unsafe abortions but they have really reduced. We used to see about 40 a year and now it’s one or two." However, problems still exist. "There are some complications, like irregular bleeding from some contraceptives," Rewda says, and that "women still face conflict with their husbands over family planning and sometimes have to go to court to fight this or divorce them.”

| 01 July 2020

In pictures: Ensuring confidentiality, safety, and care for sex workers

Meseret* and Melat*, volunteers Known in their local community as demand creators, Meseret and Melat, from the Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia’s (FGAE) confidential clinic head out to visit sex workers in Jimma town. This group of volunteers are former, or current, sex workers teaching others how to protect themselves from sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancy. Their work is challenging, and they travel in pairs for safety - their messages are not always welcome. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Meseret* and Melat*, volunteers Meseret and Melat from the Jimma clinic talk to sex workers in their local community about sexual health concerns, as well as provide contraception. “It’s very difficult to convince sex workers to come to the clinic. Some sex workers tend to have no knowledge, even about how to use a condom.” says Meseret. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Melat, volunteer It can be challenging persuading women that the staff at the confidential clinic are friendly towards sex workers and will keep their information private. “When we try to tell people about HIV we can be insulted and told: ‘You are just working for yourself and earn money if you bring us in.’ They sometimes throw stones and sticks at us,” said 25-year-old Melat. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Fantaye, sex worker Getting information and contraception to women often involves going out to find them, such as Fantaye, a sex worker currently living in a rental space in Mekelle. Peer educators focus on areas populated with hotels and bars and broker's houses, where sex workers find clients. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Sister Mahader, FGAE Sister Mahader from FGAEs' youth centre talks to sex workers in Mekelle, about sexual health, wellbeing, and various methods of contraception. This outreach takes place weekly where information and advice is given to groups of women, and contraception is provided free of charge. Under threat from the loss of funding from the US Administration, the Jimma clinic has been forced to reduce the range of commodities available to its clients such as sanitary products, soap and water purification tablets. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Hiwot Abera*, sex worker Hiwot* after her appointment at FGAEs confidential clinic in Jimma. The clinic offers free and bespoke healthcare including HIV and STI testing, treatment and counselling, contraceptives and safe abortion care. Many sex workers have experienced stigma and discrimination at other clinics. In contrast, ensuring confidentiality and a safe environment for the women to talk openly is at the heart of FGAEs’ healthcare provision at its clinics.*pseudonymPhotos: ©IPPF/Zacharias Abubeker Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email

| 17 May 2025

In pictures: Ensuring confidentiality, safety, and care for sex workers

Meseret* and Melat*, volunteers Known in their local community as demand creators, Meseret and Melat, from the Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia’s (FGAE) confidential clinic head out to visit sex workers in Jimma town. This group of volunteers are former, or current, sex workers teaching others how to protect themselves from sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancy. Their work is challenging, and they travel in pairs for safety - their messages are not always welcome. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Meseret* and Melat*, volunteers Meseret and Melat from the Jimma clinic talk to sex workers in their local community about sexual health concerns, as well as provide contraception. “It’s very difficult to convince sex workers to come to the clinic. Some sex workers tend to have no knowledge, even about how to use a condom.” says Meseret. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Melat, volunteer It can be challenging persuading women that the staff at the confidential clinic are friendly towards sex workers and will keep their information private. “When we try to tell people about HIV we can be insulted and told: ‘You are just working for yourself and earn money if you bring us in.’ They sometimes throw stones and sticks at us,” said 25-year-old Melat. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Fantaye, sex worker Getting information and contraception to women often involves going out to find them, such as Fantaye, a sex worker currently living in a rental space in Mekelle. Peer educators focus on areas populated with hotels and bars and broker's houses, where sex workers find clients. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Sister Mahader, FGAE Sister Mahader from FGAEs' youth centre talks to sex workers in Mekelle, about sexual health, wellbeing, and various methods of contraception. This outreach takes place weekly where information and advice is given to groups of women, and contraception is provided free of charge. Under threat from the loss of funding from the US Administration, the Jimma clinic has been forced to reduce the range of commodities available to its clients such as sanitary products, soap and water purification tablets. Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email Hiwot Abera*, sex worker Hiwot* after her appointment at FGAEs confidential clinic in Jimma. The clinic offers free and bespoke healthcare including HIV and STI testing, treatment and counselling, contraceptives and safe abortion care. Many sex workers have experienced stigma and discrimination at other clinics. In contrast, ensuring confidentiality and a safe environment for the women to talk openly is at the heart of FGAEs’ healthcare provision at its clinics.*pseudonymPhotos: ©IPPF/Zacharias Abubeker Share on Twitter Share on Facebook Share via WhatsApp Share via Email

| 29 June 2020

“I used to be a sex worker, so I have a shared experience with them"

Emebet Bekele is a former sex worker turned counsellor, who works at the Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia (FGAE) run, confidential clinic in Jimma, Oromia. The clinic was set up in 2014 to help at-risk and underserved populations such as sex workers. The clinic provides free and bespoke services that include HIV and STI testing, treatment and counselling, contraceptives and comprehensive abortion care. Counselling sex workers In her new role, Emebet counsels others about HIV and treatment with anti-retroviral drugs, follows up with them and monitors their treatment. Emebet tries to be a role model for other girls and women who are sex workers to adopt a healthier lifestyle “The nature of the sex work business is very mobile, and they often go to other places when the coffee harvest is good, so I tell them about referrals and take their phone numbers so I can keep counselling them”. “The difficult thing is sex workers using alcohol and drugs with ARVs [anti-retrovirals], which is not good and also means that they forget to take their medication. The best thing is that I know and understand them because I passed through that life. I know where they live so I can call them and drop medicine at their homes.” Bekele regularly tests sex workers and every month, “a minimum of five out of a hundred, maximum ten” test positive for HIV. An increase in HIV cases Over the last five years, her reports show an increase in the number of HIV cases due to more sex workers coming in or changing clinics to attend the confidential clinic. Partly because the staff are friendly towards sex workers, who often report facing stigma in other public hospitals or being turned away when staff hear what they do. At the confidential clinic, people can walk-in any time, which better suits the sex worker lifestyle, but crucially, the service is confidential. “The ARV clinics in government hospitals are separate so everyone knows you have HIV. Also, people will see others crying and say that they have HIV,” says Bekele. A shared experience “I used to be a sex worker, so I have a shared experience with them. When I came to this clinic I taught people about this place and the services and I counsel and train them. I didn’t have any knowledge about sex work so I also got infected. When I got knowledge, I decided I wanted to do something to help others.” “Sometimes clients add extra money for sex without condoms and sometimes sex workers have been drinking and don’t notice their clients have not used condoms. To have sex using a condom usually costs about 300 Ethiopian Birr [roughly USD 7] but it can go as low as 50 Birr [USD 1.20] or 20 Birr [USD 0.50], whereas sex without using a condom costs 200 to 300 Birr more or even up to 1000 Birr [USD 24].” When Bekele was a sex worker, she would take home about 7,000 to 8,000 Birr per month [roughly USD 170 to 190], after paying job-related expenses such as hotels, as well as for substances like alcohol to get through it. As a counsellor, she now gets 2,000 Birr to cover her travel costs. “I have already stopped and I’m now a model for these girls. I have financial problems but life is much more than money.” “I see girls aged 10, 13 and 15 who live on the streets and take drugs. Sometimes we bring them from the streets and test them. Most of them are pregnant and I help them.” “This project is useful for our country because there aren’t any others helping sex workers and if there are ways to help them, we save many lives and young people. If you teach one sex worker, you teach everyone, from government to university staff and anyone who goes to see them, so I save many lives doing this job.”

| 17 May 2025

“I used to be a sex worker, so I have a shared experience with them"

Emebet Bekele is a former sex worker turned counsellor, who works at the Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia (FGAE) run, confidential clinic in Jimma, Oromia. The clinic was set up in 2014 to help at-risk and underserved populations such as sex workers. The clinic provides free and bespoke services that include HIV and STI testing, treatment and counselling, contraceptives and comprehensive abortion care. Counselling sex workers In her new role, Emebet counsels others about HIV and treatment with anti-retroviral drugs, follows up with them and monitors their treatment. Emebet tries to be a role model for other girls and women who are sex workers to adopt a healthier lifestyle “The nature of the sex work business is very mobile, and they often go to other places when the coffee harvest is good, so I tell them about referrals and take their phone numbers so I can keep counselling them”. “The difficult thing is sex workers using alcohol and drugs with ARVs [anti-retrovirals], which is not good and also means that they forget to take their medication. The best thing is that I know and understand them because I passed through that life. I know where they live so I can call them and drop medicine at their homes.” Bekele regularly tests sex workers and every month, “a minimum of five out of a hundred, maximum ten” test positive for HIV. An increase in HIV cases Over the last five years, her reports show an increase in the number of HIV cases due to more sex workers coming in or changing clinics to attend the confidential clinic. Partly because the staff are friendly towards sex workers, who often report facing stigma in other public hospitals or being turned away when staff hear what they do. At the confidential clinic, people can walk-in any time, which better suits the sex worker lifestyle, but crucially, the service is confidential. “The ARV clinics in government hospitals are separate so everyone knows you have HIV. Also, people will see others crying and say that they have HIV,” says Bekele. A shared experience “I used to be a sex worker, so I have a shared experience with them. When I came to this clinic I taught people about this place and the services and I counsel and train them. I didn’t have any knowledge about sex work so I also got infected. When I got knowledge, I decided I wanted to do something to help others.” “Sometimes clients add extra money for sex without condoms and sometimes sex workers have been drinking and don’t notice their clients have not used condoms. To have sex using a condom usually costs about 300 Ethiopian Birr [roughly USD 7] but it can go as low as 50 Birr [USD 1.20] or 20 Birr [USD 0.50], whereas sex without using a condom costs 200 to 300 Birr more or even up to 1000 Birr [USD 24].” When Bekele was a sex worker, she would take home about 7,000 to 8,000 Birr per month [roughly USD 170 to 190], after paying job-related expenses such as hotels, as well as for substances like alcohol to get through it. As a counsellor, she now gets 2,000 Birr to cover her travel costs. “I have already stopped and I’m now a model for these girls. I have financial problems but life is much more than money.” “I see girls aged 10, 13 and 15 who live on the streets and take drugs. Sometimes we bring them from the streets and test them. Most of them are pregnant and I help them.” “This project is useful for our country because there aren’t any others helping sex workers and if there are ways to help them, we save many lives and young people. If you teach one sex worker, you teach everyone, from government to university staff and anyone who goes to see them, so I save many lives doing this job.”

| 20 February 2020

“Teenage pregnancies will decrease, unsafe abortions and deaths as a result of unsafe abortions will decrease"

Midwife Sophia Abrafi sits at her desk, sorting her paperwork before another patient comes in looking for family planning services. The 40-year-old midwife welcomes each patient with a warm smile and when she talks, her passion for her work is clear. At the Mim Health Centre, which is located in the Ahafo Region of Ghana, Abrafi says a sexual and reproductive health and right (SRHR) project through Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG) and the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA) allows her to offer comprehensive SRH services to those in the community, especially young people. Before the project, launched in 2018, she used to have to refer people to a town about 20 minutes away for comprehensive abortion care. She had also seen many women coming in for post abortion care service after trying to self-administer an abortion. “It was causing a lot of harm in this community...those cases were a lot, they will get pregnant, and they themselves will try to abort.” Providing care & services to young people Through the clinic, she speaks to young people about their sexual and reproductive health and rights. “Those who can’t [abstain] we offer them family planning services, so at least they can complete their schooling.” Offering these services is crucial in Mim, she says, because often young people are not aware of sexual and reproductive health risks. “Some of them will even get pregnant in the first attempt, so at least explaining to the person what it is, what she should do, or what she should expect in that stage -is very helpful.” She has already seen progress. “The young ones are coming. If the first one will come and you provide the service, she will go and inform the friends, and the friends will come.” Hairdresser Jennifer Osei, who is waiting to see Abrafi, is a testament to this. She did not learn about family planning at school. After a friend told her about the clinic, she has begun relying on staff like Abrafi to educate her. “I have come to take a family planning injection, it is my first time taking the injection. I have given birth to one child, and I don’t want to have many children now,” she says. Expanding services in Mim The SRHR project is working in three other clinics or health centres in Mim, including at the Ahmadiyya Muslim Hospital. When midwife Sherifa, 28, heard about the SRHR project coming to Mim, she knew it would help her hospital better help the community. The hospital was only offering care for pregnancy complications and did little family planning work. Now, it is supplied with a range of family planning commodities, and the ability to do comprehensive abortion care, as well as education on SRHR. Being able to offer these services especially helps school girls to prevent unintended pregnancies and to continue at school, she says. Sherifa also already sees success from this project, with young people now coming in for services, education and treatment of STIs. In the long term, she predicts many positive changes. “STI infection rates will decrease, teenage pregnancies will decrease, unsafe abortions and deaths as a result of unsafe abortions will decrease. The young people will now have more information about their sexual life in this community, as a result of the project.”

| 17 May 2025

“Teenage pregnancies will decrease, unsafe abortions and deaths as a result of unsafe abortions will decrease"

Midwife Sophia Abrafi sits at her desk, sorting her paperwork before another patient comes in looking for family planning services. The 40-year-old midwife welcomes each patient with a warm smile and when she talks, her passion for her work is clear. At the Mim Health Centre, which is located in the Ahafo Region of Ghana, Abrafi says a sexual and reproductive health and right (SRHR) project through Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG) and the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA) allows her to offer comprehensive SRH services to those in the community, especially young people. Before the project, launched in 2018, she used to have to refer people to a town about 20 minutes away for comprehensive abortion care. She had also seen many women coming in for post abortion care service after trying to self-administer an abortion. “It was causing a lot of harm in this community...those cases were a lot, they will get pregnant, and they themselves will try to abort.” Providing care & services to young people Through the clinic, she speaks to young people about their sexual and reproductive health and rights. “Those who can’t [abstain] we offer them family planning services, so at least they can complete their schooling.” Offering these services is crucial in Mim, she says, because often young people are not aware of sexual and reproductive health risks. “Some of them will even get pregnant in the first attempt, so at least explaining to the person what it is, what she should do, or what she should expect in that stage -is very helpful.” She has already seen progress. “The young ones are coming. If the first one will come and you provide the service, she will go and inform the friends, and the friends will come.” Hairdresser Jennifer Osei, who is waiting to see Abrafi, is a testament to this. She did not learn about family planning at school. After a friend told her about the clinic, she has begun relying on staff like Abrafi to educate her. “I have come to take a family planning injection, it is my first time taking the injection. I have given birth to one child, and I don’t want to have many children now,” she says. Expanding services in Mim The SRHR project is working in three other clinics or health centres in Mim, including at the Ahmadiyya Muslim Hospital. When midwife Sherifa, 28, heard about the SRHR project coming to Mim, she knew it would help her hospital better help the community. The hospital was only offering care for pregnancy complications and did little family planning work. Now, it is supplied with a range of family planning commodities, and the ability to do comprehensive abortion care, as well as education on SRHR. Being able to offer these services especially helps school girls to prevent unintended pregnancies and to continue at school, she says. Sherifa also already sees success from this project, with young people now coming in for services, education and treatment of STIs. In the long term, she predicts many positive changes. “STI infection rates will decrease, teenage pregnancies will decrease, unsafe abortions and deaths as a result of unsafe abortions will decrease. The young people will now have more information about their sexual life in this community, as a result of the project.”

| 20 February 2020

"It has helped me a lot, without that information I would have given birth to many children..."

Factory workers at Mim Cashew, in a small town in rural Ghana, are taking their reproductive health choices into their own hands, thanks to a four-year project rolled out by Planned Parenthood Association Ghana (PPAG) along with the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA). The project, supported by private funding, focuses on factory workers as well as residents in the township of about 30, 000, where the factory is located. Under the project, health clinic staff in Mim have been supported to provide comprehensive abortion care, a range of different contraception choices and STI treatments as well as information and education. In both the community and the factory, there is a strong focus on SRHR trained peer educators delivering information to their colleagues and peers. An increase in knowledge So far, the project has yielded positive results - especially a notable increase amongst the workers on SRHR knowledge and access to services - like worker Janet Pinamang, who is a 32-year-old mother of two. She says the SRHR project has been great for her and her colleagues. "I have had a lot of benefits with the project from PPAG. PPAG has educated us on how the process is involved in a lady becoming pregnant. PPAG has also helped us to understand more on drug abuse and about HIV.” She also appreciated the project working in the wider community and helping to address high levels of teenage pregnancy. "I have seen a lot of change before the coming of PPAG little was known about HIV, and its impacts and how it was contracted - now PPAG has made us know how HIV is spread, how it is gotten and all that. PPAG has also got us to know the benefits of spacing our children." “It has helped me a lot” Pinamang's colleague, Sandra Opoku Agyemang, 27, is a mother of a six-year-old girl called Bridget. Agyemang says before the project came to Mim, she had only heard negative information around family planning. "I heard family planning leads to dizziness, it could lead to fatigue, you won't get a regular flow of menses and all that, and I also heard problems with heart attacks. I had heard of these problems, and I was afraid, so after the coming of PPAG, I went into family planning, and I realised all the things people talked about were not wholly true." Now using family planning herself, she says the future is bright for her, and her family. "It has helped me a lot, without that information I would have given birth to many children, not only Bridget. In the future, I plan to add on two [more children], even with the two I am going to plan."

| 17 May 2025

"It has helped me a lot, without that information I would have given birth to many children..."

Factory workers at Mim Cashew, in a small town in rural Ghana, are taking their reproductive health choices into their own hands, thanks to a four-year project rolled out by Planned Parenthood Association Ghana (PPAG) along with the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA). The project, supported by private funding, focuses on factory workers as well as residents in the township of about 30, 000, where the factory is located. Under the project, health clinic staff in Mim have been supported to provide comprehensive abortion care, a range of different contraception choices and STI treatments as well as information and education. In both the community and the factory, there is a strong focus on SRHR trained peer educators delivering information to their colleagues and peers. An increase in knowledge So far, the project has yielded positive results - especially a notable increase amongst the workers on SRHR knowledge and access to services - like worker Janet Pinamang, who is a 32-year-old mother of two. She says the SRHR project has been great for her and her colleagues. "I have had a lot of benefits with the project from PPAG. PPAG has educated us on how the process is involved in a lady becoming pregnant. PPAG has also helped us to understand more on drug abuse and about HIV.” She also appreciated the project working in the wider community and helping to address high levels of teenage pregnancy. "I have seen a lot of change before the coming of PPAG little was known about HIV, and its impacts and how it was contracted - now PPAG has made us know how HIV is spread, how it is gotten and all that. PPAG has also got us to know the benefits of spacing our children." “It has helped me a lot” Pinamang's colleague, Sandra Opoku Agyemang, 27, is a mother of a six-year-old girl called Bridget. Agyemang says before the project came to Mim, she had only heard negative information around family planning. "I heard family planning leads to dizziness, it could lead to fatigue, you won't get a regular flow of menses and all that, and I also heard problems with heart attacks. I had heard of these problems, and I was afraid, so after the coming of PPAG, I went into family planning, and I realised all the things people talked about were not wholly true." Now using family planning herself, she says the future is bright for her, and her family. "It has helped me a lot, without that information I would have given birth to many children, not only Bridget. In the future, I plan to add on two [more children], even with the two I am going to plan."

| 19 February 2020

“Despite all those challenges, I thought it was necessary to stay in school"

When Gifty Anning Agyei was pregnant, her classmates teased her, telling her she should drop out of school. She thought of having an abortion, and at times she says she considered suicide. When her father, Ebenezer Anning Agyei found out about the pregnancy, he was furious and wanted to kick her out of the house and stop supporting her education. Getting the support she needed But with support from Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG) and advice from Ebenezer’s church pastor, Gifty is still in school, and she has a happy baby boy, named after Gifty’s father. Gifty and the baby are living at home, with Gifty’s parents and three of her siblings in Mim, a small town about eight hours drive northwest of Ghana’s capital Accra. “Despite all those challenges, I thought it was necessary to stay in school. I didn’t want any pregnancy to truncate my future,” Gifty says, while her parents nod in proud support. In this area of Ghana, research conducted in 2018 found young people like Gifty had high sexual and reproduce health and rights (SRHR) challenges, with low comprehensive knowledge of SHRH and concerns about high levels of teenage pregnancy. PPAG, along with the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA), launched a four-year project in Mim in 2018 aimed to address these issues. For Gifty, now 17, and her family, this meant support from PPAG, especially from the coordinator of the project in Mim, Abdul- Mumin Abukari. “I met Abdul when I was pregnant. He was very supportive and encouraged me so much even during antenatals he was with me. Through Abdul, PPAG encouraged me so much.” Her mother, Alice, says with support from PPAG her daughter did not have what might have been an unsafe abortion. The parents are also happy that the PPAG project is educating other young people on SRHR and ensuring they have access to services in Mim. Gifty says teenage pregnancy is common in Mim and is glad PPAG is trying to curb the high rates or support those who do give birth to continue their schooling. “It’s not the end of the road” “PPAG’s assistance is critical. There are so many ladies who when they get into the situation of early pregnancy that is the end of the road, but PPAG has made us know it is only a challenge but not the end of the road.” Gifty’s mum Alice says they see baby Ebenezer as one of their children, who they are raising, for now, so GIfty can continue with her schooling. “In the future, she will take on the responsibly more. Now the work is heavy, that is why we have taken it upon ourselves. In the future, when Gifty is well-employed that responsibility is going to be handed over to her, we will be only playing a supporting role.” Alice also says people in the community have commented on their dedication. “When we are out, people praise us for encouraging our daughter and drawing her closer to us and putting her back to school.” Dad Ebenezer smiles as he looks over at his grandson. “We are very happy now.” When she’s not at school or home with the baby, Gifty is doing an apprenticeship, learning to sew to follow her dream of becoming a fashion designer. For her, despite giving birth so young, she has her sights set on finishing her high school education in 2021 and then heading to higher education.

| 17 May 2025

“Despite all those challenges, I thought it was necessary to stay in school"

When Gifty Anning Agyei was pregnant, her classmates teased her, telling her she should drop out of school. She thought of having an abortion, and at times she says she considered suicide. When her father, Ebenezer Anning Agyei found out about the pregnancy, he was furious and wanted to kick her out of the house and stop supporting her education. Getting the support she needed But with support from Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG) and advice from Ebenezer’s church pastor, Gifty is still in school, and she has a happy baby boy, named after Gifty’s father. Gifty and the baby are living at home, with Gifty’s parents and three of her siblings in Mim, a small town about eight hours drive northwest of Ghana’s capital Accra. “Despite all those challenges, I thought it was necessary to stay in school. I didn’t want any pregnancy to truncate my future,” Gifty says, while her parents nod in proud support. In this area of Ghana, research conducted in 2018 found young people like Gifty had high sexual and reproduce health and rights (SRHR) challenges, with low comprehensive knowledge of SHRH and concerns about high levels of teenage pregnancy. PPAG, along with the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA), launched a four-year project in Mim in 2018 aimed to address these issues. For Gifty, now 17, and her family, this meant support from PPAG, especially from the coordinator of the project in Mim, Abdul- Mumin Abukari. “I met Abdul when I was pregnant. He was very supportive and encouraged me so much even during antenatals he was with me. Through Abdul, PPAG encouraged me so much.” Her mother, Alice, says with support from PPAG her daughter did not have what might have been an unsafe abortion. The parents are also happy that the PPAG project is educating other young people on SRHR and ensuring they have access to services in Mim. Gifty says teenage pregnancy is common in Mim and is glad PPAG is trying to curb the high rates or support those who do give birth to continue their schooling. “It’s not the end of the road” “PPAG’s assistance is critical. There are so many ladies who when they get into the situation of early pregnancy that is the end of the road, but PPAG has made us know it is only a challenge but not the end of the road.” Gifty’s mum Alice says they see baby Ebenezer as one of their children, who they are raising, for now, so GIfty can continue with her schooling. “In the future, she will take on the responsibly more. Now the work is heavy, that is why we have taken it upon ourselves. In the future, when Gifty is well-employed that responsibility is going to be handed over to her, we will be only playing a supporting role.” Alice also says people in the community have commented on their dedication. “When we are out, people praise us for encouraging our daughter and drawing her closer to us and putting her back to school.” Dad Ebenezer smiles as he looks over at his grandson. “We are very happy now.” When she’s not at school or home with the baby, Gifty is doing an apprenticeship, learning to sew to follow her dream of becoming a fashion designer. For her, despite giving birth so young, she has her sights set on finishing her high school education in 2021 and then heading to higher education.

| 19 February 2020

"They teach us as to how to avoid STDs and how to space our childbirth"

As the sun rises each morning, Dorcas Amakyewaa leaves her home she shares with her five children and mother and heads to work at a cashew factory. The factory is on the outskirts of Mim, a town in the Ahafo Region of Ghana. Along the streets of the township, people sell secondhand shoes and clothing or provisions from small, colourfully painted wooden shacks. “There are so many problems in town, notable among them [young people], teenage pregnancies and drug abuse,” Amakyewaa says, reflecting on the community of about 30,000 in Ghana. The chance to make a difference In 2018, Amakyewaa was offered a way to help address these issues in Mim, through a sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR) project brought to both the cashew factory and the surrounding community, through the Danish Family Planning Association, and Planned Parenthood Association Ghana (PPAG). Before the project implementation, some staff at the factory were interviewed and surveyed. Findings revealed similar concerns Amakyewaa had, along with the need for comprehensive education, access and information on the right to key SRHR services. The research also found a preference for receiving SRHR information through friends, colleagues or factory health outreach. These findings then led to PPAG training people in the factory to become SRHR peer educators, including Amakyewaa. She now passes on what she has learnt in her training to her colleagues in sessions, where they discuss different SRHR topics. “I guide them to space their births, and I also guide them on the effects of drug abuse.” The project has also increased access to hospitals, she adds. “The people I teach, I have given the numbers of some nurses to them. So that whenever they need the services of the nurses, they call them and meet them straight away.” Access to information One of the women Amakyewaa meets with to discuss sexual and reproductive health is Monica Asare, a mother of two. “I have had a lot of benefits from PPAG. They teach us as to how to avoid STDs and how to space our childbirth. I teach my child about what we are learning. I never had access to this information; it would have helped me a lot, probably I would have been in school.” Amakyewaa also says she didn’t have access to information and services when she was young. If she had, she says she would not have had a child at 17. She takes the information she has learnt, to share with her children and other young people in the community. When she gets home after work, Amakyewaa’s peer education does not stop, she continues. She also continues her teachings when she gets home. “PPAG’s project has been very helpful to me as a mother. When I go home, previously I was not communicating with my children with issues relating to reproduction.” Her 19-year-old daughter, Stella Akrasi, has also benefitted from her mothers training. “I see it to be good. I always share with my friends give them the importance of family planning. If she teaches me something I will have to go and tell them too” she says.

| 17 May 2025

"They teach us as to how to avoid STDs and how to space our childbirth"

As the sun rises each morning, Dorcas Amakyewaa leaves her home she shares with her five children and mother and heads to work at a cashew factory. The factory is on the outskirts of Mim, a town in the Ahafo Region of Ghana. Along the streets of the township, people sell secondhand shoes and clothing or provisions from small, colourfully painted wooden shacks. “There are so many problems in town, notable among them [young people], teenage pregnancies and drug abuse,” Amakyewaa says, reflecting on the community of about 30,000 in Ghana. The chance to make a difference In 2018, Amakyewaa was offered a way to help address these issues in Mim, through a sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR) project brought to both the cashew factory and the surrounding community, through the Danish Family Planning Association, and Planned Parenthood Association Ghana (PPAG). Before the project implementation, some staff at the factory were interviewed and surveyed. Findings revealed similar concerns Amakyewaa had, along with the need for comprehensive education, access and information on the right to key SRHR services. The research also found a preference for receiving SRHR information through friends, colleagues or factory health outreach. These findings then led to PPAG training people in the factory to become SRHR peer educators, including Amakyewaa. She now passes on what she has learnt in her training to her colleagues in sessions, where they discuss different SRHR topics. “I guide them to space their births, and I also guide them on the effects of drug abuse.” The project has also increased access to hospitals, she adds. “The people I teach, I have given the numbers of some nurses to them. So that whenever they need the services of the nurses, they call them and meet them straight away.” Access to information One of the women Amakyewaa meets with to discuss sexual and reproductive health is Monica Asare, a mother of two. “I have had a lot of benefits from PPAG. They teach us as to how to avoid STDs and how to space our childbirth. I teach my child about what we are learning. I never had access to this information; it would have helped me a lot, probably I would have been in school.” Amakyewaa also says she didn’t have access to information and services when she was young. If she had, she says she would not have had a child at 17. She takes the information she has learnt, to share with her children and other young people in the community. When she gets home after work, Amakyewaa’s peer education does not stop, she continues. She also continues her teachings when she gets home. “PPAG’s project has been very helpful to me as a mother. When I go home, previously I was not communicating with my children with issues relating to reproduction.” Her 19-year-old daughter, Stella Akrasi, has also benefitted from her mothers training. “I see it to be good. I always share with my friends give them the importance of family planning. If she teaches me something I will have to go and tell them too” she says.

| 28 July 2020

"I wanted to protect girls from violence – like early marriage – and I wanted to change people’s wrong perceptions about sex and sexuality"

Seventeen-year-old student Jumeya Mohammed Amin started educating other people about sexual and reproductive health when she was 14 years old. She trained as a ‘change agent’ for her community through the Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia’s south west office in Jimma, the capital of Oromia region. Amin comes from a small, conservative town about 20km outside the city. "I wanted to protect girls from violence – like early marriage – and I wanted to change people’s wrong perceptions about sex and sexuality, because they [men in her community] start having sex with girls at a young age, even with girls as young as nine years old, because of a lack of education." "They suddenly had to act like grown-up women" "Before I started this training I saw the majority of students having sex early and getting pregnant because of a lack of information, and they would have to leave home and school. Boys would be disciplined and if they were seen doing things on campus, expelled. Girls younger than me at the time were married. The youngest was only nine. They would have to go back home and could not play anymore or go to school. They suddenly had to act like grown-up women, like old ladies. They never go back to school after marriage. My teacher chose me for this training and told me about the programme. I like the truth so I was not afraid. I heard about a lot of problems out there during my training and I told myself I had to be strong and go and fight this." "I have a brother and four sisters and I practiced my training on my family first. They were so shocked by what I was saying they were silent. Even on the second day, they said nothing. On the third day, I told them I was going to teach people in schools this, so I asked them why they had stayed silent. They told me that because of cultural and religious issues, people would not accept these ideas and stories, but they gave me permission to go and do it. Because of my efforts, people in my school have not started having sex early and the girls get free sanitary pads through the clubs so they no longer need to stay home during periods." Training hundreds of her peers "I know people in my community who have unplanned pregnancies consult traditional healers [for abortions] and take drugs and they suffer. I know one girl from 10th grade who was 15 years old and died from this in 2017. The healers sometimes use tree leaves in their concoctions. We tell them where they can go and get different [safe abortion] services. The first round of trainings I did was with 400 students over four months and eight sessions in 2017. Last year, I trained 600 people and this year in the first trimester of school I trained 400. When students finish the course, they want to do it again, and when we forget we have a session, they come and remind me. At school, they call me a teacher. I’d like to be a doctor and this training has really made me want to do that more."

| 16 May 2025

"I wanted to protect girls from violence – like early marriage – and I wanted to change people’s wrong perceptions about sex and sexuality"

Seventeen-year-old student Jumeya Mohammed Amin started educating other people about sexual and reproductive health when she was 14 years old. She trained as a ‘change agent’ for her community through the Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia’s south west office in Jimma, the capital of Oromia region. Amin comes from a small, conservative town about 20km outside the city. "I wanted to protect girls from violence – like early marriage – and I wanted to change people’s wrong perceptions about sex and sexuality, because they [men in her community] start having sex with girls at a young age, even with girls as young as nine years old, because of a lack of education." "They suddenly had to act like grown-up women" "Before I started this training I saw the majority of students having sex early and getting pregnant because of a lack of information, and they would have to leave home and school. Boys would be disciplined and if they were seen doing things on campus, expelled. Girls younger than me at the time were married. The youngest was only nine. They would have to go back home and could not play anymore or go to school. They suddenly had to act like grown-up women, like old ladies. They never go back to school after marriage. My teacher chose me for this training and told me about the programme. I like the truth so I was not afraid. I heard about a lot of problems out there during my training and I told myself I had to be strong and go and fight this." "I have a brother and four sisters and I practiced my training on my family first. They were so shocked by what I was saying they were silent. Even on the second day, they said nothing. On the third day, I told them I was going to teach people in schools this, so I asked them why they had stayed silent. They told me that because of cultural and religious issues, people would not accept these ideas and stories, but they gave me permission to go and do it. Because of my efforts, people in my school have not started having sex early and the girls get free sanitary pads through the clubs so they no longer need to stay home during periods." Training hundreds of her peers "I know people in my community who have unplanned pregnancies consult traditional healers [for abortions] and take drugs and they suffer. I know one girl from 10th grade who was 15 years old and died from this in 2017. The healers sometimes use tree leaves in their concoctions. We tell them where they can go and get different [safe abortion] services. The first round of trainings I did was with 400 students over four months and eight sessions in 2017. Last year, I trained 600 people and this year in the first trimester of school I trained 400. When students finish the course, they want to do it again, and when we forget we have a session, they come and remind me. At school, they call me a teacher. I’d like to be a doctor and this training has really made me want to do that more."

| 28 July 2020

"I'm a volunteer here, so it’s mental satisfaction I get from doing this"

Youth leader Nebiyu Ephirem, 26, has been staffing the phones at a hotline for young people who have questions about sexual and reproductive health (SRH) since it started in 2017 in Ethiopia’s Oromia region. The helpline has two phones and is free, anonymous and open six days a week. The helpline is aimed at people aged 17-26 who are curious about SRH but are too shy or afraid to ask others about topics such as contraception, menstruation, and diseases. The hotline also advises people dealing with emergencies following unprotected sex and issues such as unintended pregnancy and concerns over sexually transmitted infections (STIs), by referring people to their nearest clinic. About 65 to 70 percent of the callers are female. Ephirem also trains other people about SRH and how to educate more young people about this. Being on call for his community “Most days, I get about 30 to 40 calls and on a Saturday, around 50. People ask about contraceptive methods like pills and emergency contraceptives and depo provera [three-month injectable contraceptive], about the spread of STIs and HIV and how to prevent it, and about menstruation and sanitation. I give my suggestions and then they come and use Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia (FGAE) services, or I refer people to clinics all over the country. There are seven FGAE clinics in this area and dozens of private clinics. Young people need information about STIs before they come to the clinic, and when they want a service they can know where the clinics are. Most of them need information about menstruation and contraception. They fear discussing this openly with family and due to religious beliefs, so people like to call me. Culturally, people used to not want to discuss sexual issues. We took the information from IPPF documents and translated them into the two local languages of Oromia and Amharic, with the help of university lecturers. After four years, even the religious leaders did this training. We have trained university students, teachers and many more people to be trainers and 30 of them graduated. They [the people who dropped out] did not want to hear about the names in the local language of body parts. Most of the ones who stayed were boys and girls, but now we have women doing this. [At first], they were laughing and said: ‘How could you talk like this? It’s shameful. But slowly, they became aware. They now talk to me, they discuss things with their parents, families, even teachers at school and friends.” Lack of sex education There is no sex education in Ethiopia’s national curriculum but youth groups and activists like Ephirem and his colleagues go into schools and teach people through school clubs. “This year [2019] up to June we trained 16,000 people and reached 517,725 adolescents and young people aged 10 to 24 through the helpline, social media – Facebook, Twitter and YouTube – workshops, radio talk shows and libraries.” A banner in Jimma town promotes the helpline and its number 8155, as does Jimma FM radio. “The target for reaching people in school was 5,400. We achieved 11,658. The most effective way to reach people is at school. At the coffee plantation sites we reach a lot of people.” The minimum family size around here is about five and the maximum we see is 10 to 12. In our culture, children are [considered as a sign of] wealth and people think they are blessed [if they have many]. When we go to schools to teach them, there are kids that already have kids. But after we teach them, they generally want to finish education and have kids at 20-25-years-old. We tell people they have to have kids related to the economy and to their incomes and we calculate the costs to feed and educate them. I’m a volunteer here, so it’s mental satisfaction I get from doing this. I get 1000 Ethiopian Birr [roughly USD 30] per month for transport costs. I am also studying marketing at university and want to become a business consultant.”

| 17 May 2025

"I'm a volunteer here, so it’s mental satisfaction I get from doing this"

Youth leader Nebiyu Ephirem, 26, has been staffing the phones at a hotline for young people who have questions about sexual and reproductive health (SRH) since it started in 2017 in Ethiopia’s Oromia region. The helpline has two phones and is free, anonymous and open six days a week. The helpline is aimed at people aged 17-26 who are curious about SRH but are too shy or afraid to ask others about topics such as contraception, menstruation, and diseases. The hotline also advises people dealing with emergencies following unprotected sex and issues such as unintended pregnancy and concerns over sexually transmitted infections (STIs), by referring people to their nearest clinic. About 65 to 70 percent of the callers are female. Ephirem also trains other people about SRH and how to educate more young people about this. Being on call for his community “Most days, I get about 30 to 40 calls and on a Saturday, around 50. People ask about contraceptive methods like pills and emergency contraceptives and depo provera [three-month injectable contraceptive], about the spread of STIs and HIV and how to prevent it, and about menstruation and sanitation. I give my suggestions and then they come and use Family Guidance Association of Ethiopia (FGAE) services, or I refer people to clinics all over the country. There are seven FGAE clinics in this area and dozens of private clinics. Young people need information about STIs before they come to the clinic, and when they want a service they can know where the clinics are. Most of them need information about menstruation and contraception. They fear discussing this openly with family and due to religious beliefs, so people like to call me. Culturally, people used to not want to discuss sexual issues. We took the information from IPPF documents and translated them into the two local languages of Oromia and Amharic, with the help of university lecturers. After four years, even the religious leaders did this training. We have trained university students, teachers and many more people to be trainers and 30 of them graduated. They [the people who dropped out] did not want to hear about the names in the local language of body parts. Most of the ones who stayed were boys and girls, but now we have women doing this. [At first], they were laughing and said: ‘How could you talk like this? It’s shameful. But slowly, they became aware. They now talk to me, they discuss things with their parents, families, even teachers at school and friends.” Lack of sex education There is no sex education in Ethiopia’s national curriculum but youth groups and activists like Ephirem and his colleagues go into schools and teach people through school clubs. “This year [2019] up to June we trained 16,000 people and reached 517,725 adolescents and young people aged 10 to 24 through the helpline, social media – Facebook, Twitter and YouTube – workshops, radio talk shows and libraries.” A banner in Jimma town promotes the helpline and its number 8155, as does Jimma FM radio. “The target for reaching people in school was 5,400. We achieved 11,658. The most effective way to reach people is at school. At the coffee plantation sites we reach a lot of people.” The minimum family size around here is about five and the maximum we see is 10 to 12. In our culture, children are [considered as a sign of] wealth and people think they are blessed [if they have many]. When we go to schools to teach them, there are kids that already have kids. But after we teach them, they generally want to finish education and have kids at 20-25-years-old. We tell people they have to have kids related to the economy and to their incomes and we calculate the costs to feed and educate them. I’m a volunteer here, so it’s mental satisfaction I get from doing this. I get 1000 Ethiopian Birr [roughly USD 30] per month for transport costs. I am also studying marketing at university and want to become a business consultant.”

| 16 July 2020

"Before, there was no safe abortion"